March 21, 2014 report

Drill core evidence adds credence to iron fertilization hypothesis regarding last ice age

(Phys.org) —An international team of researchers has found evidence in drill core samples taken near Antarctica that adds credence to the iron fertilization hypothesis. In their paper published in the journal Science, the team describes how lowered nitrogen levels found in core samples helps bolster the idea that increased iron in the oceans during the last ice age caused a decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

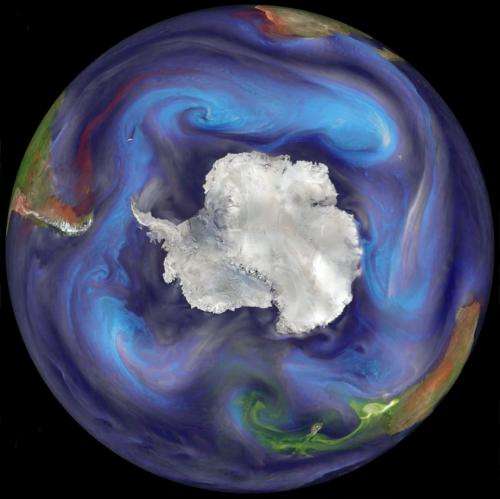

Twenty years ago, oceanographer John Martin found evidence linking a decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels during the last ice age, with an increase in ocean iron levels. It occurred, scientists reasoned, because iron is a vital nutrient for phytoplankton—when there is more iron, phytoplankton levels rise causing a fall in carbon dioxide levels because they pull it from the atmosphere. Until now however, there has been scant evidence to prove that the iron fertilization hypothesis is correct, though one group did try seeding a small part of the ocean and found localized phytoplankton levels increased along with a corresponding reduction in carbon dioxide levels. In this new effort, the researchers studied sea floor sediment core samples taken from the Sub-Antarctic Zone of the Southern Ocean.

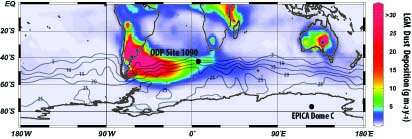

In studying the core samples, the researchers analyzed the fossilized remains of tiny sea animals, specifically those with shells. Those shells hold evidence of what the creatures ate. The researchers found nitrogen levels that were lower than in similar creatures alive today. Lower nitrogen levels suggest a higher density of nitrate eating phytoplankton, which would have occurred due to higher levels of iron in the ocean. That iron, the researchers suggest made its way to the ocean via two separate avenues during the last ice age. The first was from the wind—dust from South America and Patagonia (due to different environmental conditions) blew across the ocean leaving iron deposits. The second was from river runoff.

While the research results do add credence to the iron fertilization hypotheses, they likely also close the door on the possibly of dumping iron into the ocean to help reduce modern atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, as some scientists have suggested. The core samples indicate it would take approximately 1000 years of an increase in iron in the world's oceans to cause enough of an increase in phytoplankton to lower atmospheric carbon levels by just 40 parts per million.

More information: Iron Fertilization of the Subantarctic Ocean During the Last Ice Age, Science 21 March 2014: Vol. 343 no. 6177 pp. 1347-1350 DOI: 10.1126/science.1246848

ABSTRACT

John H. Martin, who discovered widespread iron limitation of ocean productivity, proposed that dust-borne iron fertilization of Southern Ocean phytoplankton caused the ice age reduction in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). In a sediment core from the Subantarctic Atlantic, we measured foraminifera-bound nitrogen isotopes to reconstruct ice age nitrate consumption, burial fluxes of iron, and proxies for productivity. Peak glacial times and millennial cold events are characterized by increases in dust flux, productivity, and the degree of nitrate consumption; this combination is uniquely consistent with Subantarctic iron fertilization. The associated strengthening of the Southern Ocean's biological pump can explain the lowering of CO2 at the transition from mid-climate states to full ice age conditions as well as the millennial-scale CO2 oscillations.

Journal information: Science

© 2014 Phys.org