Paper-thin e-skin responds to touch by lighting up

A new milestone by engineers at the University of California, Berkeley, can help robots become more touchy-feely, literally.

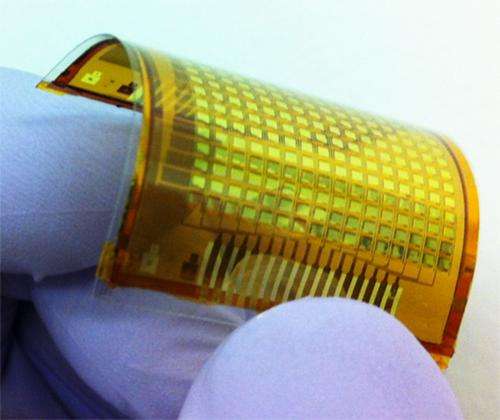

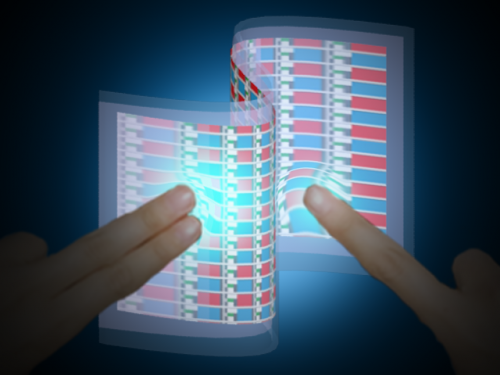

A research team led by Ali Javey, UC Berkeley associate professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences, has created the first user-interactive sensor network on flexible plastic. The new electronic skin, or e-skin, responds to touch by instantly lighting up. The more intense the pressure, the brighter the light it emits.

"We are not just making devices; we are building systems," said Javey, who also has an appointment as a faculty scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "With the interactive e-skin, we have demonstrated an elegant system on plastic that can be wrapped around different objects to enable a new form of human-machine interfacing."

This latest e-skin, described in a paper to be published online this Sunday, July 21, in the journal Nature Materials, builds on Javey's earlier work using semiconductor nanowire transistors layered on top of thin rubber sheets.

In addition to giving robots a finer sense of touch, the engineers believe the new e-skin technology could also be used to create things like wallpapers that double as touchscreen displays and dashboard laminates that allow drivers to adjust electronic controls with the wave of a hand.

"I could also imagine an e-skin bandage applied to an arm as a health monitor that continuously checks blood pressure and pulse rates," said study co-lead author Chuan Wang, who conducted the work as a post-doctoral researcher in Javey's lab at UC Berkeley.

The experimental samples of the latest e-skin measure 16-by-16 pixels. Within each pixel sits a transistor, an organic LED and a pressure sensor.

"Integrating sensors into a network is not new, but converting the data obtained into something interactive is the breakthrough," said Wang, who is now an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Michigan State University. "And unlike the stiff touchscreens on iPhones, computer monitors and ATMs, the e-skin is flexible and can be easily laminated on any surface."

To create the pliable e-skin, the engineers cured a thin layer of polymer on top of a silicon wafer. Once the plastic hardened, they could run the material through fabrication tools already in use in the semiconductor industry to layer on the electronic components. After the electronics were stacked, they simply peeled off the plastic from the silicon base, leaving a freestanding film with a sensor network embedded in it.

"The electronic components are all vertically integrated, which is a fairly sophisticated system to put onto a relatively cheap piece of plastic," said Javey. "What makes this technology potentially easy to commercialize is that the process meshes well with existing semiconductor machinery."

Javey's lab is now in the process of engineering the e-skin sensors to respond to temperature and light as well as pressure.

Provided by University of California - Berkeley