January 29, 2013 report

Fossil remains in museum found to be 165 million year old marine super-predator

Bob Yirka

news contributor

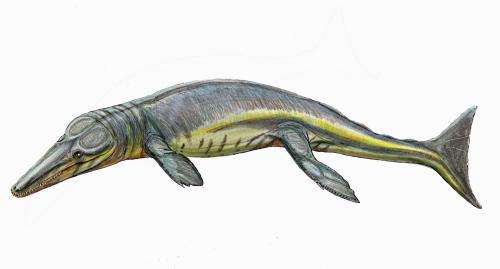

(Phys.org)—Researchers examining a fossil specimen discovered in a museum storage bin have found it to be the remains of a super-predator that lived during the Jurassic Period, around 165 million years ago. They describe the specimen, named Tyrannoneustes lythrodectikos, in their paper published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, as looking like a cross between a modern dolphin and a shark or crocodile.

Tyrannoneustes lythrodectikos, meaning "tyrant swimmer that bites" in Latin, was found in 1919 in a clay pit near the British town of Peterborough (the Oxford Clay Formation) by an amateur bone collector. Since that time it has resided, hidden away in Glasgow's Hunterian museum. The skeletal remains include a jawbone with serrated teeth that the researchers, from the University of Edinburgh describe as an indication that the creature was a super-predator – one that preys on animals that are as big as it is, or even bigger.

The research team, led by Mark Young, says the time period during which the tyrant swimmer lived would have had it swimming in the shallow seas that covered much of Europe and England – along with other large marine predators. At the time, the area consisted of a chain of islands. They believe T. lythrodectikos would have been a very strong swimmer – it had a fluked tail and forelimbs that resembled flippers and was able to open its mouth very wide to allow for biting into large prey. It would have been both a formidable hunter and an elusive target for other larger marine animals. But if caught, would not have been difficult to eat as it lacked the bony armor of other species of the time.

The Middle Jurassic period, as has been glamorized by Hollywood, was a time during which many very large animals existed, many of them predatory. Their existence, scientists say, indicates a time when there was a very healthy food chain.

The team adds that the species is the oldest known super-predator, and notes that little research had been done on the skeletal remains over the near century since it was brought to the museum. They also report that no stomach contents were found, thus they can't say for sure what the animal ate.

Written for you by our author Bob Yirka—this article is the result of careful human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive. If this reporting matters to you, please consider a donation (especially monthly). You'll get an ad-free account as a thank-you.

Publication details

The oldest known metriorhynchid super-predator: a new genus and species from the Middle Jurassic of England, with implications for serration and mandibular evolution in predacious clades, DOI:10.1080/14772019.2012.704948

Abstract

The Oxford Clay Formation of England has yielded numerous sympatric species of metriorhynchid crocodylomorphs, although disagreement has persisted regarding the number of valid species. For over 140 years teeth reminiscent of the genus Dakosaurus have been known from the Oxford Clay Formation but these have never been properly described and their taxonomy and systematic affinity remain contentious. Furthermore, an enigmatic mandible and associated postcranial skeleton discovered by Alfred Leeds in the Fletton brick pits near Peterborough also remains undescribed. We show that this specimen, and several isolated teeth, represents the oldest known remains of a large-bodied predatory metriorhynchid. This material is described herein and referred to Tyrannoneustes lythrodectikos gen. et sp. nov. This species has a unique occlusal pattern: the dentition was arranged so that the posterior maxillodentary teeth interlock in the same plane and occlude mesiodistally. It is the first described crocodylomorph with microscopic denticles that are not contiguous along the carinae (forming short series of up to 10 denticles) and do not noticeably alter the height of the keel. Additionally, the dorsally expanded and curved posterior region of the mandible ventrally displaced the dentary tooth row relative to the jaw joint facilitating the enlargement of the dentition and increasing optimum gape. Therefore, Tyrannoneustes would have been a large-bodied marine predator that was well-suited to feed on larger prey than other contemporaneous metriorhynchids. A new phylogenetic analysis finds Tyrannoneustes to be the sister taxon to the subclade Geosaurini. An isolated tooth, humerus, and well-preserved mandible suggest a second species of metriorhynchid super-predator may also have lived in the Oxford Clay sea. Finally, we revise the diagnoses and descriptions of the other Oxford Clay metriorhynchid species, providing a guide for differentiating the many contemporaneous taxa from this exceptional fossil assemblage.

Journal information: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology

© 2013 Phys.org