Astronomers observe fast growing primitive black holes

(PhysOrg.com) -- Astronomers have come across what appear to be two of the earliest and most primitive supermassive black holes known. The discovery, based largely on observations from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, will provide a better understanding of the roots of our universe, and how the very first black holes, galaxies and stars came to be.

"We have found what are likely first-generation quasars, born in a dust-free medium and at the earliest stages of evolution," said Linhua Jiang of the University of Arizona, Tucson. Jiang is the lead author of a paper announcing the findings in the March 18 issue of Nature.

Black holes are beastly distortions of space and time. The most massive and active ones lurk at the cores of galaxies, and are usually surrounded by doughnut-shaped structures of dust and gas that feed and sustain the growing black holes. These hungry, supermassive black holes are called quasars.

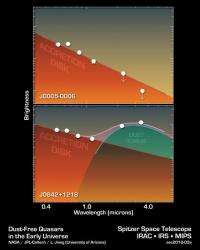

As grimy and unkempt as our present-day universe is today, scientists believe the very early universe didn't have any dust -- which tells them that the most primitive quasars should also be dust-free. But nobody had seen such immaculate quasars -- until now. Spitzer has identified two -- the smallest on record -- about 13 billion light-years away from Earth. The quasars, called J0005-0006 and J0303-0019, were first unveiled in visible light using data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. That discovery team, which included Jiang, was led by Xiaohui Fan, a coauthor of the recent paper at the University of Arizona. NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory had also observed X-rays from one of the objects. X-rays, ultraviolet and optical light stream out from quasars as the gas surrounding them is swallowed.

"Quasars emit an enormous amount of light, making them detectable literally at the edge of the observable universe," said Fan.

When Jiang and his colleagues set out to observe J0005-0006 and J0303-0019 with Spitzer between 2006 and 2009, their targets didn't stand out much from the usual quasar bunch. Spitzer measured infrared light from the objects along with 19 others, all belonging to a class of the most distant quasars known. Each quasar is anchored by a supermassive black hole weighing more than 100 million suns.

Of the 21 quasars, J0005-0006 and J0303-0019 lacked characteristic signatures of hot dust, the Spitzer data showed. Spitzer's infrared sight makes the space telescope ideally suited to detect the warm glow of dust that has been heated by feeding black holes.

"We think these early black holes are forming around the time when the dust was first forming in the universe, less than one billion years after the Big Bang," said Fan. "The primordial universe did not contain any molecules that could coagulate to form dust. The elements necessary for this process were produced and pumped into the universe later by stars."

The astronomers also observed that the amount of hot dust in a quasar goes up with the mass of its black hole. As a black hole grows, dust has more time to materialize around it. The black holes at the cores of J0005-0006 and J0303-0019 have the smallest measured masses known in the early universe, indicating they are particularly young, and at a stage when dust has not yet formed around them.

The Spitzer observations were made before the telescope ran out of its liquid coolant in May 2009, beginning its "warm" mission.

Provided by JPL/NASA