Europe's Mars orbiter is healthy says 'relieved' ESA (Update)

UPDATE: Ground controllers re-established full links Sunday with a European-Russian Mars orbiter which worryingly stopped sending status updates after releasing a lander on a three-day trek to the Red Planet's surface.

"Everything is back on track," spokeswoman Jocelyne Landeau-Constantin of the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, told AFP by telephone, surrounded by "a lot of relieved people".

An overnight manoeuvre will continue as planned to steer the orbiter off a collision course with Mars, she added.

Earlier story:

Europe's Mars orbiter not sending status data: ESA

Ground controllers reported a break Sunday in status data from a European-Russian Mars orbiter after it released a tiny lander on a three-day trek to the Red Planet's surface.

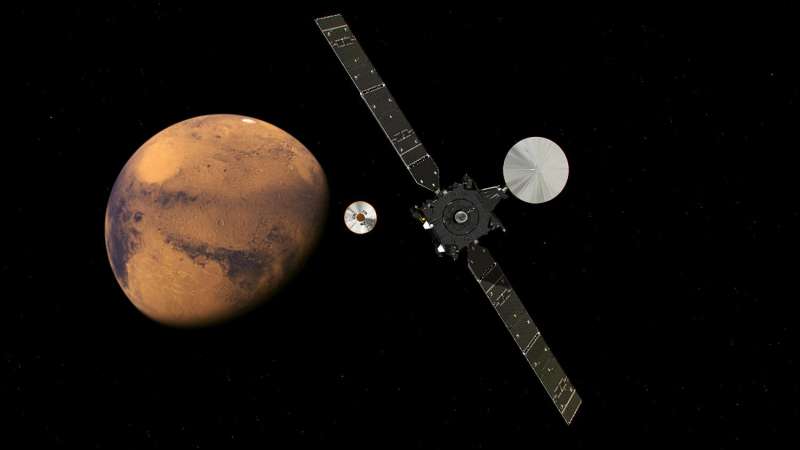

The Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) was sending signals home, but "we don't have telemetry at the moment", flight director Michel Denis of the ExoMars mission said via live webcast from mission control in Darmstadt, Germany.

Ground controllers were "working towards restoring telemetry", according to a tweet from ESA Operations.

The Schiaparelli test lander's separation from its mothership earlier Sunday, at about one million kilometres (621,000 miles) from the Red Planet's surface, had "gone perfectly well", said spokeswoman Jocelyne Landeau-Constantin of the European Space Operations Centre.

"But after that we were supposed to get some indication of the status of the orbiter, its position, its status, and we didn't get this sort of information," she told AFP by telephone from Darmstadt.

Ground controllers are now looking at other types of data to try and determine what happened, as the cutoff approaches for an overnight "uplift" manoeuvre to remove the TGO from a collision course with Mars.

It could be that the lander separation was "a bit more violent than expected", and that this may have caused the break in telemetry, said Landeau-Constantin.

"It's not that dramatic," she added. "At one point we will be able to get in touch with it. It's just that they need to know exactly where it was at the time of separation, in which status it was.

"Nothing is lost, it's just that they need to work a bit harder and a bit longer."

Earlier Sunday, as planned, the 600-kilogramme (1,300-pound), paddling pool-sized Schiaparelli separated from the TGO after a seven-month, 496-million-km trek from Earth.

Schiaparelli's main goal is to test entry and landing gear and technology for a subsequent rover which will mark the second phase and highlight of the ExoMars mission.

Thirteen years after its first, failed, attempt to place a rover on Mars, the high-stakes test is a key phase in Europe's fresh bid to reach our neighbouring planet's hostile surface, this time working with Russia.

Facts behind Europe and Russia's ExoMars mission

Europe will send a test lander Sunday on a one-way trip to the Martian surface, a key step in its joint ExoMars project with Russia to search for life on the Red Planet.

Some facts about the mission:

What's in a name?

ExoMars gets its name from "exobiology"—the science of analysing the odds and likely nature of life on other planets.

Schiaparelli, the lander, was named after a 19th century Italian astronomer who had observed lines, which he called "canali", on Mars through a telescope

This was mistranslated into English as canal (instead of channel), which cause many to imagine vast irrigation networks built by intelligent creatures.

Better telescopes in the 20th century killed off that legend.

In numbers:

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) spacecraft, which will analyse our neighbour's atmosphere, measures 3.5 metres by two metres by two metres (11.5 feet by 6.5 feet by 6.5 feet).

It has solar wings spanning 17.5 metres, tip to tip.

With the Schiaparelli lander on board, it travelled 496 million kilometres (308 million miles) to get to Mars.

On Sunday, the TGO will release Schiaparelli from a distance of one million kilometres from the Red Planet's surface.

The paddling pool-sized lander, 1.6 metres wide, will test entry and landing gear for a subsequent rover to be launched in 2020.

Why?

Scientists believe Mars once hosted liquid water—a key ingredient for life as we know it.

While the Martian surface is too dry, cold and radiation-blasted to sustain life today, this may have been a different story 3.5 billion years ago when the Red Planet's climate was warmer and wetter.

Science has long abandoned the hunt for little green men, though.

Life, if any exists, is likely underground—away from harmful ultraviolet and cosmic rays—and in the form of single-celled microbes.

Primitive or not, it would be the first time humans ever observe life on a planet other than Earth.

The mission will also seek to learn more about geological processes on Mars, and about the sand storms that change the face of the planet with their seasonal violence.

How?

TGO will taste Martian gases, looking specifically for methane.

Methane is important because it may be a clue to life—on Earth it is mostly produced by biological processes.

Previous missions had already picked up traces of methane in Mars' atmosphere, but the TGO has much more sophisticated tools with which scientists hope to tell whether the gas is biological or geological in origin.

Methane can, theoretically, also be created by underground volcanoes.

The rover will drill into Mars to look for evidence of buried, extinct life, or even live microbic activity.

Who?

While diplomatic ties between Europe and Russia may be under strain, they collaborate closely on ExoMars—a shared project of Roscosmos and the European Space Agency (ESA).

Europe has budgeted 1.3 billion euros ($1.4 billion) for the mission

America's NASA, which was due to contribute $1.4 billion, pulled out due to budget cuts in 2012, causing Europe to turn to Russia.

Moscow agreed to provide launcher rockets in exchange for science instruments onboard the craft.

The lander, Schiaparelli, is European, and the rover will be too. The platform housing the rover and its science lab will be Russian.

Prestige:

"We need to demonstrate our ability to do things on our own," ESA senior scientist Mark McCaughrean told AFP of the European quest.

"It's partly about proving that Europe has the capability and the will and the power to pull these projects together."

© 2016 AFP