Peregrine chicks lost in recent inclement weather

The excitement and hope two peregrine falcon chicks created was dashed with the spring storms that passed through Terre Haute earlier this week.

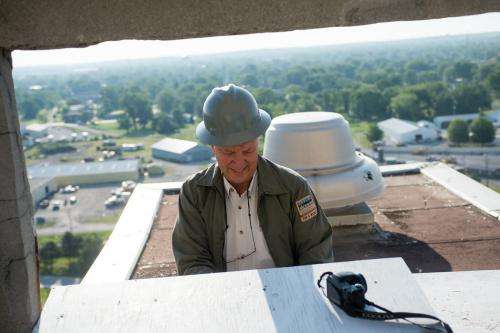

The female chicks, about four weeks old, were banded and documented on May 28, by officials from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Fish and Wildlife. Then Wednesday, university officials recovered the body of one chick at the base of Indiana State University's now vacant Statesman Towers, and the second chick was not in the rooftop nest box.

"We do not know what happened to the second (chick).There is some slim chance that it survived and will be found, but very slim," said biology professor Steven Lima, who attributed the cause being storms that passed through the area Tuesday night.

The hatching was the second of such event in western Indiana in at least 50 years, Lima said. The first was in 2010, when the same male falcon successfully mated with a different female and hatched three chicks.

While disappointing for bird enthusiasts, the chicks' demise is not completely unexpected, as relatively few peregrine falcon chicks make it to adulthood, Lima said.

"Most of them die. It's that simple fact of life as a bird," Lima said. "It's hard to get established. Once they're an adult, they have a pretty good life expectancy."

Peregrine falcons eat other birds—small-to-medium-sized ones such as pigeons, blue jays and woodpeckers—and like to sit and nest on tall buildings or stacks, said John Castrale, nongame bird biologist for DNR.

"They surprise birds in the air, and they come into a real quick dive—they're the fastest animal in the world, with speeds up to 200-plus mph," Castrale said. "These aren't the hawks that people see at their feeders—those are usually Cooper's hawks or sharp-shinned hawks. I get a lot of calls about peregrine falcons at people's feeders, but that's not the case."

Peregrine falcons became endangered in the 1960s because of the wide use of the insecticide DDT that poisoned their food supply. As top predators, the birds absorbed large amounts of the chemical from ingesting their prey and became unable to reproduce.

Efforts to reintroduce the birds in the 1970s got off to a rocky start, Lima said, because the birds were released in wooded and wild areas, where there were too many predators and other obstacles to survival.

"Biologists started to introduce them into cities, and then it got much more successful at that point. There weren't many owls in cities to kill them, so they did pretty well," Lima said.

Now, there are about two dozen pairs in Indiana, mostly near Lake Michigan, Castrale said.

"Every year, we try to band most of the babies in the state. There's about 16, 17 nests this year that we're trying to get to, so our population is relatively small," Castrale said when he passed through Terre Haute last week.

There are about 300 pairs in the Midwest, he said.

"From a historical standpoint, this species is doing well. They've been taken off the federal endangered species list and then last year, we took them off the state list. They're still a special concerned species, so we still try to monitor their nests and locations in the state," Castrale said. "We appreciate the university and building managers for hosting these birds. Without that, they wouldn't have a safe place to nest. It really contributes to the increase in their population."

Provided by Indiana State University