Space for dessert?

(Phys.org) -- All chefs know that preparing the perfect chocolate mousse is one part science and one part art. ESA’s microgravity research is helping the food industry understand the science behind the foams found in many types of food and drink such as meringues and coffee.

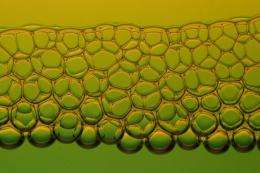

Not all foams are created equal. Consumers expect a chocolate mousse to keep its structure and taste on the journey from the supermarket to their fridge. But the froth on some drinks would seem strange if it did not disappear after a few minutes.

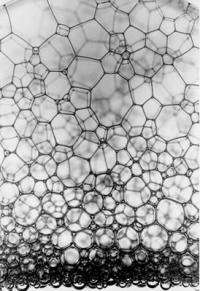

Creating the right type of foam on demand is tricky. Liquid flows downwards on Earth and foams are torn apart by gravity pulling on the bubbles.

Foams are easier to study in weightlessness because the bubbles are evenly spread rather than the larger bubbles floating to the top.

ESA has been investigating foams since the 1980s. Our knowledge and knowhow caught the attention of food company Nestlé over 10 years ago.

“Gaining a better understanding of foam may help to improve the texture of our products,” says Dr Cécile Gehin-Delval, a scientist at the Nestlé Research Centre.

“Stable foam in chocolate mousse gives the feeling of creaminess in the mouth. To make fine coffee froth, we want to create stable little bubbles to make it light and creamy.”

Creating foams in microgravity is not as straightforward as it might seem – scientists mainly know how they form on Earth. After some experiments, a design was found that uses electromagnetically powered pistons to whip the liquids into shape.

Nestlé has researched the issue on ESA’s parabolic aircraft flights, where they tested hardware and looked at milk protein for 20 seconds at a time during periods of weightlessness.

Parabolic flights are only one of the ways scientists can study phenomena in ‘zero-gravity’. Sounding rockets offer up to six minutes of weightlessness but the International Space Station is the only permanent microgravity laboratory available.

Now that researchers have proven their experiment hardware can make and analyse foams on parabolic flights, they are looking at continuing their study on the Space Station.

ESA’s Olivier Minster explains: “Around half of the products found in a typical fridge are based on foams and emulsions. If we can create more stable foams without adding ingredients this will improve their shelf-life.”

Unfortunately for the astronauts on the Space Station, scientists need only small quantities for testing. There is no chance they will be allowed to taste the results.

Provided by European Space Agency