Genetic research shows degeneration in ageing worm

Genetic research focusing on the soil nematode C. elegans has generated fundamental new insights into the way in which these tiny worms age. During the ageing process, the activity of the worm's genes gradually becomes more turbulent and gene regulation declines. Because degenerative processes in worms and humans are similar, the research results offer clues for the prevention and medication of geriatric diseases. Researchers at Wageningen University publish their findings in the online edition of the journal Genome Research this week.

The nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans is just one millimetre long and is naturally found in the soil. The worm is often used in fundamental biological research. Many worm genes also occur in humans and perform comparable, vital functions in life processes such as breathing and cell division. The degenerative process in the nematode C. elegans is therefore a model for the changes which take place in the ageing human being. Despite intensive research over the past twenty years, it is still unclear when and how the degeneration of the body occurs.

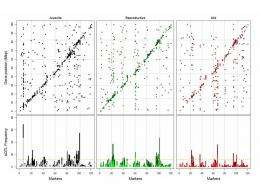

Led by Jan Kammenga, the research team from Wageningen University, part of Wageningen UR - chair group Nematology - analysed activity in the totality of the genes (the so-called genome) in C. elegans, which numbers approximately 18,000 genes. They also measured genome activity both in young nematodes (40 hours old) and older nematodes which are no longer able to reproduce (214 hours old), among dozens of different strains of worms which vary in genome composition.

Comparison of the activity showed that in the young nematodes, the level of gene expression is even and constant: the level of activity barely varies. In the older worms, by contrast, there is a large fluctuation in gene expression. Some groups of genes have low gene expression, much lower than in young worms, while other gene groups exhibit tumultuous activity, much higher than in young worms. “Like the lid flying off a pan of boiling water”, as one of the researchers, Ana Viñuela, put it.

In order to see whether this activity is caused by regulatory functions being lost with age, the team compared the gene expression of the various strains with the genome of each. That comparison showed that the number of genes which regulate themselves falls with age, while the number of genes regulated from elsewhere in the genome rises. This means that regulation is taking place in multiple steps, making it more vulnerable to disruption.

But this pattern shows a particular development. A limited set of genes are in fact regulated in a targeted way by a single group of regulators. This set of genes has been found to be capable of extending the lifespan of C. elegans and is therefore of vital importance. They play an important protective role against all kinds of stress factors. “We have discovered new regulatory factors which play a role in the overall degeneration of the genetic code which influences lifespan,” says Kammenga.

For the first time, the research offers an understanding of the dynamics of gene expression regulation over the entire lifespan of an organism. Fellow researcher Basten Snoek says it is “brilliant to see that there are gene expression patterns which are hereditary”. The use of C. elegans as a model for such research is hard to match. Mice, rats and other test animals which resemble humans more closely than C. elegans live too long to be able to conduct a complete age test on a large scale. Experimental genetic research in humans is impossible for practical and ethical reasons. The worm is therefore an excellent model for this type of research. The results can be used to investigate gene expression variation in older humans in a more focused way and to look for comparable regulators to the worm's. This could lead to new receptors for prevention and medication to treat geriatric diseases, such as particular types of cancer.

More information: Genome-wide gene expression regulation as a function of genotype and age in C. elegans. Ana Viñuela, L. Basten Snoek, Joost A.G. Riksen, Jan E. Kammenga. Laboratory for Nematology, Wageningen University. Genome Research, 30 June 2010 (paper edition).

Provided by Wageningen University