This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

The science of color: How color blindness creates unseen barriers in science

Dr. Mark Lindsay was 5 years old when he first learned that tree trunks were brown.

"Up until that point, I believed leaves and trunks were all green. Just lighter and darker shades," Mark said.

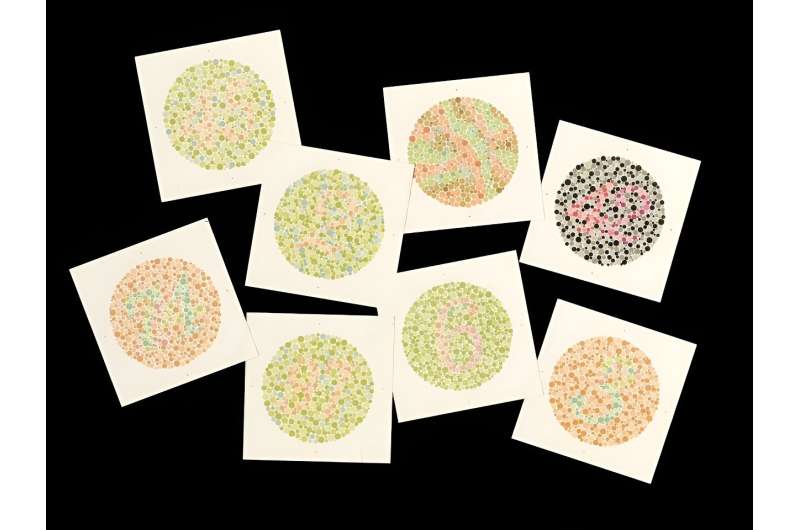

Mark had discovered he was color blind. Color blindness, or color vision deficiency (CVD), is a visual impairment that affects an individual's ability to perceive certain colors accurately.

Mark is now a geologist. He inherited his color vision deficiency from his grandfather. In a twist of fate, his grandfather was also a geologist.

To succeed in science, Mark has learned not to make assumptions about his view of the natural world. Instead, he's constantly aware that everyone sees things differently.

A hidden handicap

The primary cause of color blindness is the absence or malfunction of photoreceptor cells in the retina, known as cones.

Cone cells are responsible for detecting light and color. They come in three types: red, green, and blue. Each type is sensitive to a specific range of wavelengths. The brain interprets various colors based on the signals received from cone cells.

Color blindness typically results from a genetic mutation that affects one or more of these cone types. And men are more frequently affected than women.

The most common types of color blindness are:

- Deuteranomaly (red-green color blindness). The most common form of color blindness, deuteranomaly affects the green cone cells. People with deuteranomaly have difficulty distinguishing between red and green hues.

- Protanomaly (red-green color blindness), affects the red cone cells. People with this type struggle to differentiate between red and green colors.

- Tritanomaly (blue-yellow color blindness) which is caused by the malfunction of blue cone cells. This affects the ability to perceive blue and yellow colors, and

- Monochromacy (complete color blindness), a rare condition which occurs when an individual has only one type of cone or no functional cones at all. This means they see the world in grayscale.

Color perceptions

While people with normal vision can see a visual symphony of colorful vegetables in the image above, the perception is somewhat different for color-blind individuals.

You can use a color blindness simulator, to get a sense of how people with different types of color vision deficiency perceive the same picture.

A world of unseen data

Scientists work to make the unseen seen. To do this, they use an array of strategies to visualize scientific results and concepts.

Conveying complex data is tricky. Often, the most effective approach is using colored visualizations. The detailed visual data presentations common in science often fail to accommodate those with color blindness, rendering some information effectively invisible to them.

Imagine a climate change map depicting temperature variations through a gradient of colors. For someone with color blindness, these variations aren't evident; the design effectively blocks them from "seeing" the data.

This scenario extends to diverse scientific fields. From astronomy to medicine, color-coded information is integral to conveying patterns, trends, and anomalies. And the implications extend far beyond inconvenience. A researcher could misinterpret data due to a rainbow color gradient. Or a physician could misdiagnose a condition because they lose critical information in the chromatic shuffle.

The rainbow conundrum

Rainbow-like and red-green color maps are top offenders for accessibility. While visually appealing, these color schemes pose challenges for people with color blindness.

The uneven distribution of colors and the dominance of certain hues can lead to misinterpretations, affecting the accuracy of scientific conclusions.

For example, bright yellows and subtle greens may morph into an undecipherable palette for some color-blind individuals. This can erase nuances in crucial data.

Making data accessible and inclusive

With many journals requesting color blind-friendly scientific illustrations, what can we do to make color-coded science data more accessible?

"Color palettes used in charts and figures cause the most confusion for scientists," Mark said.

Black and white is the safest option. But sometimes, color is king.

"To be color-blind sensitive, avoid using red and green together. Use contrast to ensure your text and background colors are easy to read. Also consider using icons or symbols instead of colored text labels for your data points."

Software is also providing solutions.

"A lot of software used for data visualization now have options to adapt to, adjust for or accommodate a range of color vision deficiencies. Thankfully, many palettes for the color-blind are offered by the major software packages in Python, R and Matlab," Mark said.

When in doubt, Mark recommends you check it out using a color-blindness simulator.

Seeing on the spectrum

The beauty of science lies not just in what we see but in our collective ability to make the unseen visible.

"Educating people to consider color accessibility when communicating data and concepts is a great first step," Mark said.

"By considering the challenges posed by color blindness in science we begin to break down barriers. We also enrich the scientific narrative by enabling more diverse perspectives."

Provided by CSIRO