July 10, 2023 feature

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

The rise and fall of the Roman empire preserved in pollen

Sediments at the bottom of the ocean can offer a window into the past, indicating environmental conditions not just from the sea but washed in from terrestrial runoff, as well as preserving the flora and fauna of the time. Scientists access this knowledge by taking exploration cruises to core the seabed, bringing these cores to the surface for analysis in laboratories.

One such expedition, reported in The Holocene, recovered cores from the Gulf of Saint Eufemia, on the west coast of Calabria, Italy. Knowing the size of the basin from which the cores are obtained is important as it helps to identify the spatial distribution of where sediments and inclusions, such as pollen and spores, have been derived; larger basins could be capturing material on land from hundreds of meters away, giving information on regional vegetation patterns, whereas small basins are more likely to capture material from the immediate vicinity and therefore offer a more localized picture of plant communities.

Studying pollen grains and spores preserved in these cores (palynology), researchers from the University of Naples Federico II, Italy, and their collaborators were able to chart the colonization of Italy by Greeks and Romans during the past 5,000 years. To do so, pollen was extracted from the sediment (up to an astonishing 12,000 grains per gram of material) and analyzed under a microscope, with 72 species identified.

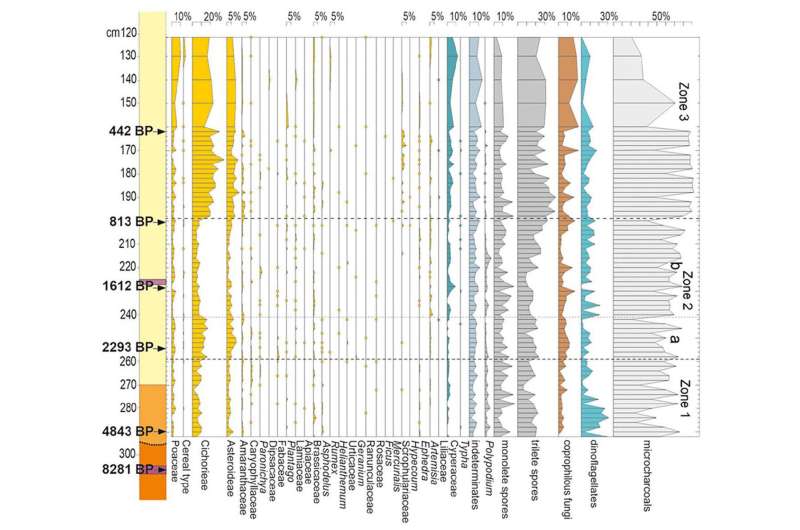

The results revealed three distinct phases of vegetation in the region: dense forest cover between 5055 and 2700 years before present (BP), forest decline and aridity between 2700 and 2000 BP, and deforestation with intensive agriculture from 790 BP to present day.

These vegetation patterns can be closely linked with the communities living in the area at the time with Pre-Protohistoric populations finding a home in the dense forest. However, they may have begun to see the effects of climate change as the researchers note three lengthy periods of hundreds of years in which the vegetation indicates arid conditions proliferated in the area.

The second phase corresponded to the rise of Greek (7th to 5th century BC) and Roman (3rd to 2nd century BC) populations in the area, with evidence of reduced forest cover, instead being replaced by agricultural intensification based upon the preservation of cereals and herbs of the Cichorieae tribe (with familiar members being lettuce, chicory and dandelion).

High abundance of microcharcoals in the sediments compared to the preceding phase is a key indicator of population increase also, as they preserve the remains of burning for cooking and heating.

Meanwhile, in the final phase, widespread deforestation destabilized soil and increased water runoff, evidenced by increased sedimentation rates. The authors also note that during the 6th century AD, the change in sedimentation rate is most likely linked to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the region, with a sudden decline in land management meaning ruralization.

This is further supported by a reduction in microcharcoals found in the samples as communities lessened combustion activities, as well as declining fir pollen as these trees were cut down for timber (a resource that was previously well-managed by the Romans, but saw local over-exploitation after their exit from the area).

Coupled with archaeological studies of the Mediterranean basin, palynology is an important indicator of vegetation changes as a result of human occupation of the area. The climate in Italy over the last 5,000 years (middle and late Holocene) has been punctuated by a series of cooler and drier periods, and so it is likely a combination of both urbanization and climate change impacting plant communities through time and space.

Today, the region experiences a number of microclimates due to altitude, with average annual temperatures ranging from 7°C to 16°C. In the mountains, tree populations are dominated by turkey oak and beech, with a smaller contribution of firs, while pine and oak are found along the coast, alongside agricultural land. Palynologists of the future may well experience exactly the same conundrum of disentangling climate and human influences on our local landscapes.

More information: Halinka Di Lorenzo et al, A high-resolution record of landscape changes and land use over the last 5000 years in western Calabria (S. Eufemia Gulf, southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy), The Holocene (2023). DOI: 10.1177/09596836231176487

Journal information: The Holocene

© 2023 Science X Network