Indigenous-led supportive housing can be transformative

Look to any urban center in Canada and you will find First Nations, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) peoples disproportionately experiencing homelessness.

FNMI people make up an alarming 66% of the homeless population in Winnipeg, 33% in Vancouver and Victoria and 16% in Montreal and Toronto.

This pervasive trend is symptomatic of Canada's intensifying housing crisis, coupled with the insidious impacts of past and present colonial policies. There is also a lack of housing models that take into consideration FNMI cultural knowledge and the voices of FNMI people.

Looking to and learning from existing Indigenous-led and community-informed models may bring us one step closer to addressing this disparity.

Shifting the focus

Current conversations around FNMI homelessness are dominated by pathways into homelessness, with minimal focus on pathways out—although these pathways do exist.

One example of an FNMI-led solution comes from the ancestral homelands of Coast Salish, Nuu-Chah-Nulth and Kwakwaka'wakw Nations (known today as Vancouver Island).

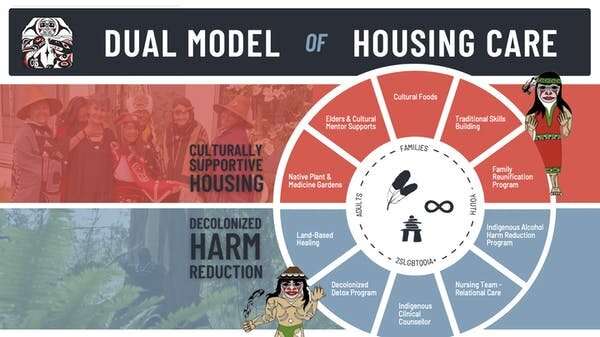

In 2020, the Aboriginal Coalition to End Homelessness (ACEH) opened British Columbia's first Culturally Supportive Housing, which operates according to its Dual Model of Housing Care (DMHC).

In collaboration with the ACEH, one of the authors (Lauren Brown) undertook a comparative analysis that revealed how the DMHC is distinct from existing models. Her analysis showed that the DMHC goes beyond housing provision by providing pathways to healing that are deeply rooted in culture, land-based programming and family reunification.

Stories shared by the ACEH staff and FNMI Street Family (unhoused people) in Victoria revealed the value of the DMHC and the opportunities for scaling it.

The DMHC's two pillars—Culturally Supportive Housing and Decolonized Harm Reduction—have introduced a comprehensive way to directly address some of the barriers FNMI people face when accessing provincial housing. These include systemic discrimination and racism; inflexibility of program policies; accessibility and the staff's lack of cultural awareness and training.

Culturally Supportive Housing offers Elder support, access to medicine keepers, ceremony, language, Indigenous medicine gardens, traditional foods and cultural activities, with love and no judgment. Decolonized Harm Reduction complements this programming with land-based camps, a family reunification program and an Indigenous alcohol harm reduction program—an Indigenized detox program is set to launch in late 2022.

Through these programs, pathways to healing and recovery have been attained for previously unhoused FNMI people.

Jack's transformation

Early in its development the ACEH met Jack, a First Nations man who had been experiencing homelessness in B.C. for more than 30 years. In 2020, Jack entered the ACEH's Culturally Supportive Housing.

He shared with us that before coming to the ACEH: "I forgot who I was as a Native person … I'm a street person, I'm a bum, right?" His reflection revealed the influential relationship between cultural (dis)connection, self-identity and housing.

Once in Culturally Supportive Housing, Jack built a connection with Elder Gloria Roze, took up his artistic practice and stewarded a garden—he no longer felt the constant need to do whatever he could to get by. These survival-driven ways of thinking were soon replaced by healing thoughts and feeling at home.

Jack's pivotal moment of clarity and transformation came at a land-based camp. It was in this healing environment—outside the confines of the city—where he received a sign to pursue treatment. It has now been two years and with support from ACEH, Jack has been living in independent housing ever since.

Bringing FNMI people home

For others like Jack across urban centers in Canada, Indigenous-led local adaptations of the DMHC can help open a pathway to healing and recovery—one that instills pride, purpose and belonging. And creating this pathway has become a matter of urgency.

With FNMI children making up 52.2% of those in foster care, rising incarceration rates among FNMI people and existing barriers to housing, many will continue to be left without somewhere to live and thrive.

Scaling the DMHC model begins with accounting for FNMI diversity. For each Indigenous community and organization, adaptation must consider local protocol, practice and social systems, it must honor the voices of FNMI Street Family and strengthen relations with those on whose territory the project will operate. It also involves addressing the federal funding shortfall for Indigenous housing providers so they can plan and build capacity and solutions.

The introduction of the DMHC has set healing in motion for FNMI people on Vancouver Island. Let Jack's story be a source of inspiration and reminder that scaling this model is a worthwhile pursuit. And one so urgently needed.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()