Snakes, rats and cats: the trillion dollar invasive species problem

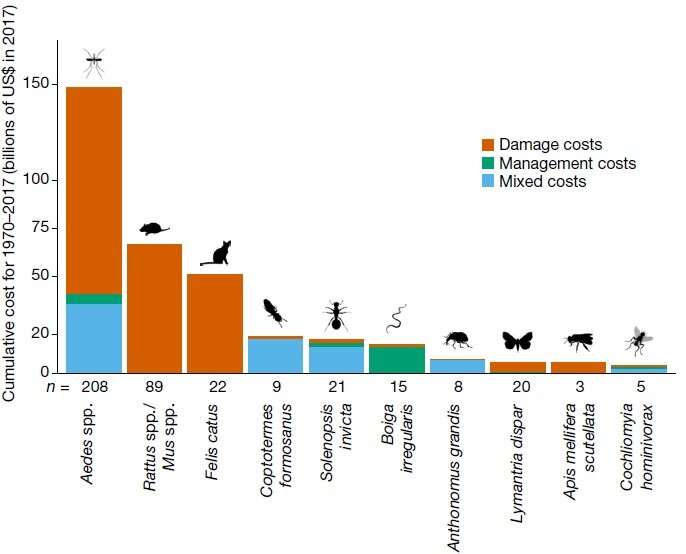

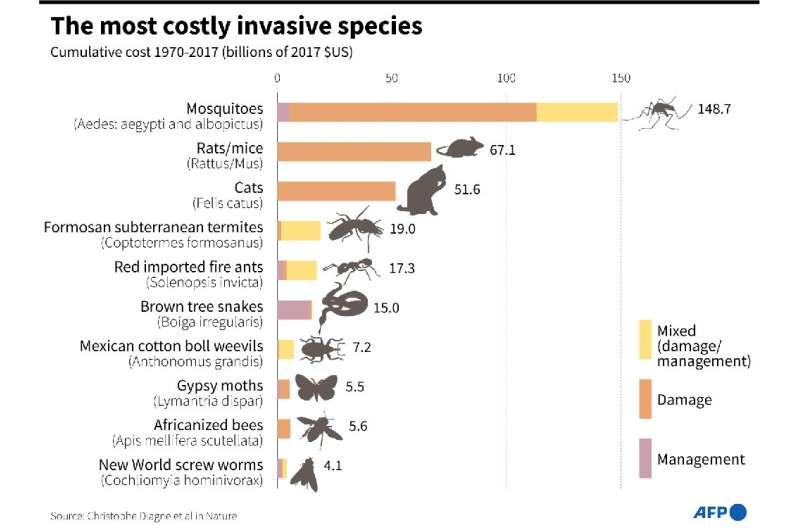

Disease-carrying mosquitoes, crop-ravaging rodents, forest-eating insects and even the domestic cat are all "exotic" intruders whose cost to humanity and the environment is vast and growing, according to a sweeping study published Wednesday.

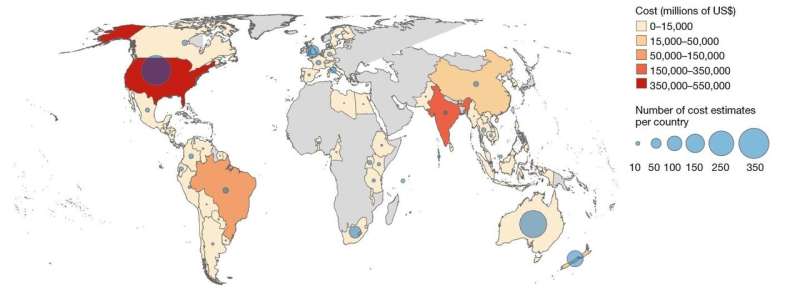

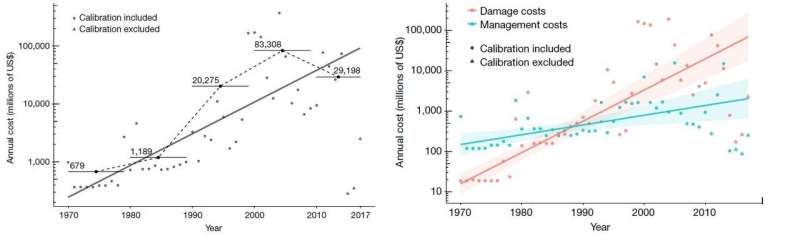

Researchers in France estimate that invasive species have cost nearly $1.3 trillion dollars to the global economy since 1970, an average of $26.8 billion per year.

And they warn that this is likely an underestimate.

In a study published in the journal Nature, scientists totted up the dizzying array of harmful effects from species carried between habitats, whether plants, insects, reptiles, birds, fish, molluscs, micro-organisms or mammals.

Beyond the "phenomenal magnitude" of these costs, there is also sign of a steady upward trend since 1970, said lead author Christophe Diagne, of the Ecology, Systematics and Evolution laboratory at the University of Paris-Saclay.

Most of the price tag is associated with the damage to ecosystems, crops or fisheries, although pest-control measures were also included in the research, an analysis of hundreds of studies that are part of a new invasive species database.

A preliminary roundup of the top ten invasive pests includes crop-eating rats and the Asian gypsy moth, which is attacking trees throughout the northern hemisphere.

It also included the tiger mosquito, native to Southeast Asia, which has become one of the worst invasive species in the world, carrying diseases like chikungunya, dengue and zika.

Average annual costs triple every decade, researchers said, in part because of an increase in scientific studies on this subject.

But there is also evidence of an "exponential increase in introduced species, due to growing international trade," said Franck Courchamp, director of the same Paris-Saclay laboratory.

"We import lots of species, voluntarily or involuntarily," he said.

Musseling in

It is a problem with a long history, linked to human trade, travel and colonialism.

In Australia, feral European rabbit populations were first reported in the early 1800s and their population exploded, reaching such proportions that they ravaged native species and caused billions of dollars of damage to crops.

In 1950, the government released the disease myxomatosis, which only affects rabbits, killing over 90 percent of the wild bunnies. But some have since built up immunity.

The brown tree snake has eaten nearly all of the native birds and lizards of Guam since it was accidentally introduced in the mid-twentieth century from its South Pacific habitat, as well as causing power outages by infiltrating electrical installations and menacing people in their homes.

In the 1980s and 90s the zebra mussel, which originated in the waterways of the former Soviet Union, invaded North America's Great Lakes, blocking pipes, threatening native species and causing billions in damages.

On land, American forests—and more recently those in Europe—have been devastated by the Asian long-horned beetle.

While in Hawaii, the Puerto Rican coqui frog has found a new home with no natural predators—except local homeowners whose property values have tumbled thanks to its ear-splitting croak, which can reach 100 decibels.

'Incalculable'

Researchers hope that by putting a number on the cost of invasive species they can raise awareness of the enormity of the problem and push it higher on humanity's daunting list of environmental challenges.

But beyond the monetary estimate, the study said the "ecological and health impacts of invasions are at least as significant, yet often incalculable".

The UN's science advisory panel for biodiversity, called IPBES, has said invasive species are among the top five culprits—all human-driven—of environmental destruction worldwide, along with changes to land use, resource exploitation, pollution and climate change.

In 2019, IPBES estimated there had been a 70 percent increase in invasive species since 1970, in the 21 countries studied.

And the worst could be to come, said Courchamp, who is taking part in upcoming IPBES research.

"International trade will cause more and more species to be introduced, while climate change will cause more and more of these introduced species to survive and become established," he said.

Early detection, better data and preventative measures could reduce costs considerably, the study said.

Courchamp said the domestic cat also has a lot to answer for—among the worst, in fact, in the researchers' top ten.

The animal, which has been taken across the world for hundreds of years, is now "invasive in almost all the islands of the world", he said.

Domestic cats have been responsible for "the most killings in the world of birds, reptiles and amphibians, which are not prepared for this type of predator", he added.

More information: High and rising economic costs of biological invasions worldwide, Nature (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03405-6 , www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03405-6

Journal information: Nature

© 2021 AFP