US: Mountain pine tree that feeds grizzlies is threatened

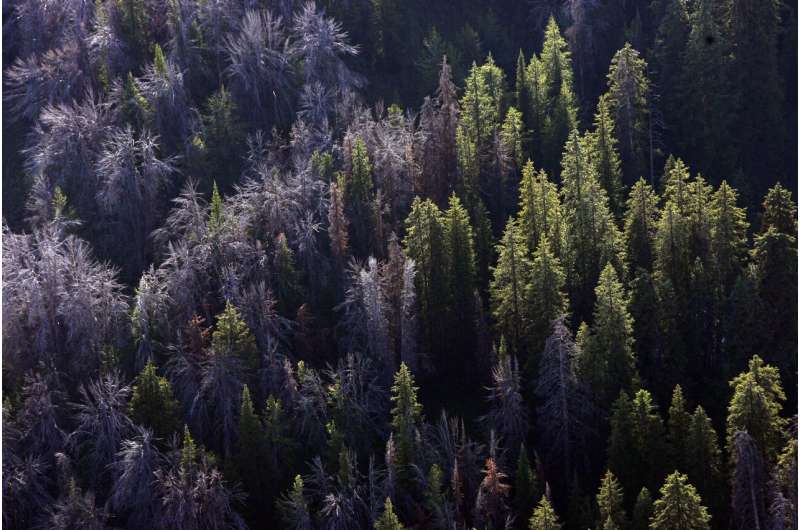

Climate change, voracious beetles and disease are imperiling the long-term survival of a high-elevation pine tree that's a key source of food for some grizzly bears and found across the West, U.S. officials said Tuesday.

A Fish and Wildlife Service proposal scheduled to be published Wednesday would protect the whitebark pine tree as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, according to documents posted by the Office of the Federal Register.

The move marks a belated acknowledgement of the tree's severe declines in recent decades and sets the stage for restoration work. But government officials said they do not plan to designate which forest habitats are critical to the tree's survival, stopping short of what some environmentalists argue is needed.

Whitebark pines can live up to 1,000 years and are found at elevations up to 12,000 feet (3,600 meters)—conditions too harsh for most tress to survive.

Environmentalists had petitioned the government in 1991 and again in 2008 to protect the trees, which occur across 126,000 square miles (326,164 square kilometers) of land in Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada and western Canada.

A nonnative fungus has been killing whitebark pines for a century. More recently, the trees have proven vulnerable to bark beetles that have killed millions of acres of forest, and climate change that scientists say is responsible for more severe wildfire seasons.

The trees have been all but wiped out in some areas, including he endangered rusty patched bumblebee.

The bee's population has plummeted 90 percent over about two decades. As with whitebark pine, loss of the bee's habitat was considered less important than other threats.

The two cases underscore a pattern of opposition to habitat protections by the administration of President Donald Trump, environmentalists said.

The Fish and Wildlife Service under Trump also has proposed rules to restrict what lands can be declared worthy of protections and to give greater weight to the economic benefits of development.

"It's clear that the intent is to limit protection of habitat for threatened and endangered species. Whitebark pine is another example of that," said Noah Greenwald with the Center for Biological Diversity.

Fish and Wildlife Service Wyoming Field Supervisor Tyler Abbott said it would not be prudent to designate areas for habitat protections since the major threats to the trees' survival can't be addressed through land management.

"The driving factor (in the tree's decline) is that white pine blister rust, and that's working synergistically with mountain pine beetle, the altered fire regime, climate change," Abbott said. "These are biological factors that we really don't have any control over."

© 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.