Designer babies: Moratorium on genome editing needed, say experts

Experts from seven countries called Wednesday for a moratorium on the kind of genetic manipulation—known as germline editing—used last year to permanently modify the genome of twin girls in Shenzhen, China.

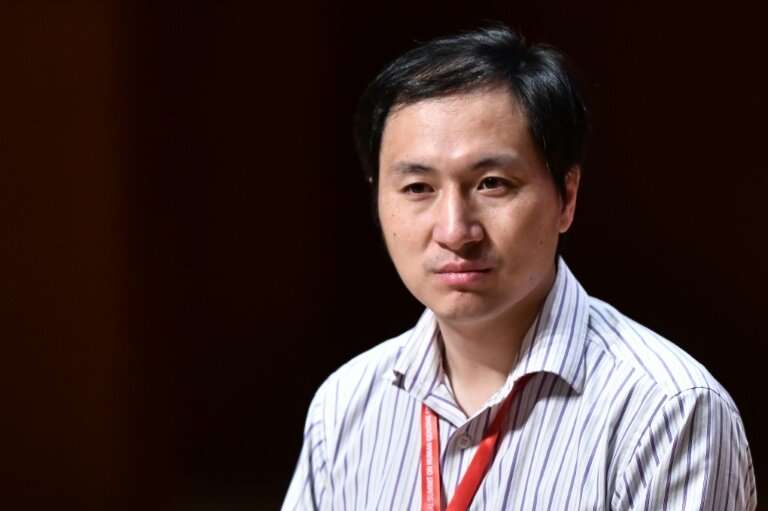

Chinese scientist He Jiankui's announcement in November that he had altered their DNA using molecular scissors—ostensibly to prevent them from contracting HIV—provoked a global backlash from scientists saying the untested procedure was unethical and potentially dangerous.

"We call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing—that is, changing the heritable DNA in sperm, eggs or embryos to make genetically modified children," the researchers said in a joint statement, published in the scientific journal Nature.

"The introduction of genetic modifications into future generations could have permanent and possibly harmful effects on the species," they warned.

About 30 nations currently have legislation directly or indirectly barring all clinical use of germline editing.

CRISPR-Cas9 technology—which combines DNA strands with an enzyme to achieve ultra-precise genome editing—can be used to correct genetic defects in a singe organism, plant or animal.

But it can also be used to introduce desirable traits that can be passed on to future generations, a science-fiction scenario that has firmly, and quite suddenly, entered the realm of the possible.

Fired from his university, He is under police investigation and has been ordered to halt his work. Last month, the Chinese government unveiled new rules to supervise biotech research, including stiff sanctions for scientists who break the rules.

Genetic enhancement

"By 'global moratorium', we do not mean a permanent ban," the authors, led by president and founding director of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Eric Lander, said.

"Rather, we call for the establishment of an international framework in which nations—while retaining the right to make their own decisions—voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met."

Such a temporary ban would not, for example, apply to pure research.

The 18 signatories distinguished between "genetic correction" aimed, for example, at modifying rare genetic mutations linked to a specific disease, and "genetic enhancement" designed to boost intelligence, memory, or muscle performance.

Such improvements, they noted, could even include the creation of new biological functions, such as the ability to see infrared light or break down certain toxins.

"Genetic enhancement of any sort would be unjustifiable at this time," the researchers said.

"Attempting to reshape the (human) species on the basis of our current state of knowledge would be hubris."

"The issue of genetic correction is more complex," the added.

Under their proposal, governments would publically declare that they will not permit any clinical use of human germline editing for a period of, say, five years.

A country could then choose to allow a specific usage, but only after an additional period of public notice and a transparent debate on the pros and cons.

Too many unanswered questions

The next step would to evaluate all the ramifications—scientific, medical, social, ethical and moral— to determine if the procedure is justified.

Finally, society would need to add its stamp of approval, perhaps through a legislative process or a referendum.

"Whether such a moratorium would be effective is one point being actively debated by the research community," Nature noted in a separate editorial.

Indeed, scientists reacted differently to the proposal.

"There is no doubt that genome editing technologies hold huge potential for the future health of patients, but I agree that the clinical use of germline editing should remain prohibited," opined Robert Lechler, president of the Academy of Medical Sciences in Britain.

"There are currently just too many unanswered safety, ethical and scientific questions."

The proposed moratorium has also been backed by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

But other researchers expressed doubt that such a measure could deter use of new gene-editing technologies given the promise for treating genetic diseases, and the lure of enhancement.

"Let's not forget that He Jiankui broke many rules, and was aware of this by choosing to do his work outside of the auspices of the university," said Helen O'Neill, program director for reproductive science and women's health at University College London.

"It was not that he did this because the law allowed it."

More information: Adopt a moratorium on heritable genome editing, Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-019-00726-5 , www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00726-5

Journal information: Nature

© 2019 AFP