A fight for both land and culture in the face of climate change

Gooraman Swamp is dry. The leaves of the stately River Red Gums that dot the area are parched and limp.

The drought and irrigators upstream on the Murray-Darling Basin are taking their toll on this wetland. But it is not just the environmental impact of climate change on his country that has Murrawarri man Fred Hooper worried.

It is also a fear that he is witnessing his cultural traditions fade away.

Those River Red Gums are not just iconic native fauna, they are spirit trees and the means through which Hooper and his people connect with their past.

"That's our connection back to the ancestors. That's how we talk to ancestors through those trees. Every time we walked into those spirit trees the wind would blow up ... that's the old fellas talking to us, up in the sky camp …. It is like someone going to church and speaking to god," Hooper says.

The swamp, when flooded, is also not just home to, and breeding grounds for, thousands of birds, it is a key element of the journey Mundaguddah, the rainbow serpent, makes across Murrawarri land linking together a series of significant water places.

"The rainbow serpent travels the land via the waterways and if it can't do that then it means the stories aren't told to the children and the next generation and the stories will die," Hooper says.

"Water is important to First Nations people across the country. Lack of flooding creates a disconnect with the landscape for First Nation people… we can't use the landscape for teaching our younger generation our cultural practices."

Hooper says these examples emphasise the different perspective Indigenous people have of climate change.

Non-Indigenous people, he says, view climate change through a prism of mass species extinction and ecosystem degradation. Yet to Indigenous people it presents a deeper challenge – there is the need to protect and care for sacred sites, and to also stand firm against a second round of colonisation.

These challenges form the pillars of what is a growing movement uniting Indigenous communities across the globe – Indigenous climate justice – was the focus of discussions at UTS this week when the Climate Justice Research Centre and Indigenous Economies Network brought together activists, academics and Indigenous representatives from Australia, India and the US for a workshop and public lecture.

Workshop co-convenor Professor Heidi Norman, a descendent of the Gomeroi people of north-west NSW, says Indigenous communities in the three countries shared a "growing mobilisation and activism against extractive industries that are environmentally damaging".

She says the fight for Indigenous climate justice is about confronting the power of capital.

Potawatomi nation member and academic, Professor Kyle Powys Whyte, from Michigan State University, agrees. Powys Whyte says the fight by Australian First Nations has echoes in struggles in the US by Indigenous Americans such as the recent fight over the Dakota Access Pipeline through Sioux lands.

"Indigenous climate justice is about stopping the financial, cultural and political forces that make for harmful relationships with the environment," he says. However he warns the longstanding history of state repression and colonisation suggests Indigenous nations will again be brought into head-on conflict with capital and state.

He says media and scientific portrayals of the world under climate change paint a dystopian future.

Yet for many Indigenous people that apocalyptic vision is already a reality: "Many of the concerns people have with climate change, if you put it in perspective, are problems Indigenous peoples have already endured through colonialism in places like the U.S. and Australia. Whether through land dispossession, forced removal or landscape change, Indigenous peoples have had to adapt to new environments repeatedly due to European and settler colonisation.

"I think many Indigenous peoples are concerned that today's conversations about climate change do not go far enough to dismantle the ways in which colonialism still operates today to make it so that Indigenous peoples will suffer more negative climate change impacts than others."

Hooper has experience of that first hand, pointing to the Murray Darling Basin Plan and the lack of consideration given to the 40 distinct First Nations people, who still live in its catchment.

He points out that First Nations peoples have rights and a moral obligation to care for water under their law and customs. Yet surprisingly to Hooper and other Indigenous activists in the region their cultural needs were not considered in water flow plans.

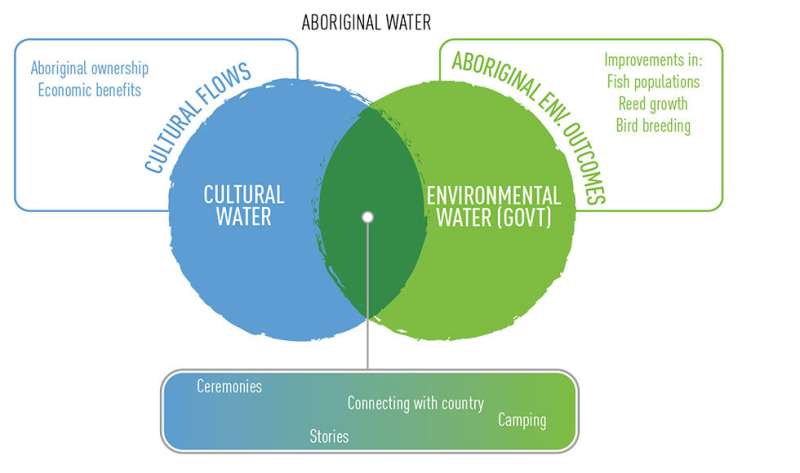

They have embraced that neglect as a challenge and through the Cultural Flows Research Project are working out how to ensure sacred places such as Gooraman Swamp receive the water they need.

As part of that research, the team completed a "use and occupancy mapping project" to determine how Indigenous Australians interacted with the landscape today. Even Hooper was astonished by the findings: with just 107 people surveyed, the team recorded 26,000 sites of use in the waterways of north-western NSW, including hunting, important sites, cultural activities and bush tucker sites.

"It shows that despite drought, climate change and man-made obstructions to water we are still using the water system as First Nation Peoples," says Hooper.

Norman says the work of people like Hooper and Powys Whyte is important because it moves the debate away from the 'Noble Savage' ideal of Indigenous people in harmony with the land and positions them as scientists and holders of knowledge.

"We don't want to have to function as a moral conscience that relies on us being imagined as pre-modern," she says. Powys Whyte is also wary of and wearied by the 'new-age' embrace of Indigenous wisdom by colonisers.

"Today we are still in a situation where often people who are concerned about the environment want to learn from Indigenous wisdom so that they can save themselves from catastrophe," he says.

"Often particular Indigenous cultural practices are threatened by climate change. Yet non-Indigenous parties often see those as opportunities to publicise how bad climate change is. Even though this publicity often raises awareness of Indigenous issues, it rarely motivates people to work on the deeper problems of land tenure, racism and inequality that will continue to create environmental justice problems for Indigenous peoples well into the future."

Provided by University of Technology, Sydney