March 28, 2018 report

Archaeologists open ancient Egyptian coffin thought to be empty and find it contains mummy remains

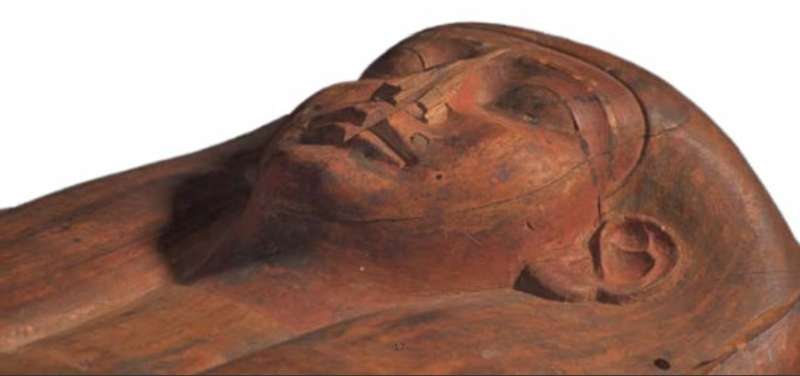

A team of archaeologists working at a University of Sydney Museum was recently surprised to discover mummy remains inside of an ancient coffin that was thought to be empty. The team has detailed their discovery and subsequent efforts to study the remains in Muse, a University of Sydney publication.

As the team notes, the coffin was acquired by the university for placement in the museum by the museum's founder, Sir Charles Nicholson, who classified the coffin as empty—that was 150 years ago, and the coffin was stored unstudied all this time, as no one knew there was anything to study. But last year, as a part of a project to take a closer look at all of its early Egyptian artifacts, the team opened the coffin, and to their surprise, found the mummy remains inside.

The mummy and coffin are believed to be approximately 2,500 years old, though the mummy itself has not yet been officially dated. There is a strong suspicion that the coffin contains the remains of an Egyptian priestess named Mer-Neith-it-es—her name was mentioned on the hieroglyphics inscribed on the coffin. Initial study of the remains suggests they are those of a 30-year-old woman, which would fit with previous information regarding the priestess.

Thus far, study of the coffin's contents has involved taking photographs to record the exact layout of the material inside and laser scanning to create 3-D models of the remains. The mummy, the team notes, is not whole. Someone, perhaps tomb raiders, jostled and damaged the contents, some of which were removed. But there is enough to offer clues, the team adds, which will be followed as the remains are subjected to closer scrutiny. They are hoping to find material suitable for carbon dating, such as toenails. CT scans have thus far shown that the material in the coffin contains bones, resin fragments, bandages and several thousand beads, presumed to be from a funeral shawl.

The find offers a unique research opportunity, the team reports, because it has been jostled, damaged and taken apart—complete mummies, in contrast, are not taken apart to peek inside because it would ruin them. This one, they point out, has already been ruined.

© 2018 Phys.org