The well-being paradox—people are getting richer, but not more satisfied

For decades, there was a single main indicator of how countries were faring—the growth of gross domestic product. But earnings do not say much about how healthy people are. Jan-Pieter Smits, professor at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) and senior statistics researcher at Statistics Netherlands (CBS), is the spiritual father of a new measuring instrument that gives policymakers a better understanding of societal well-being. It shows, among other things, that Dutch wealth from the 1970s onward started to run out of step with wider well-being.

Economists now widely believe that economic growth as a compass for government policy is harmful in the long run. "There is a growing dissatisfaction in society. "Society wants something else," says statistics researcher Jan-Pieter Smits. He has been working on an ambitious project since the 1990s, a "new compass" for overseas policy worldwide. At the request of the United Nations, the European Commission and the OECD, he developed a new model together with a large team. It has now been approved by the statistics offices of 65 countries, and in the Netherlands, a report based on this measurement system is even a topic of a parliamentary debate.

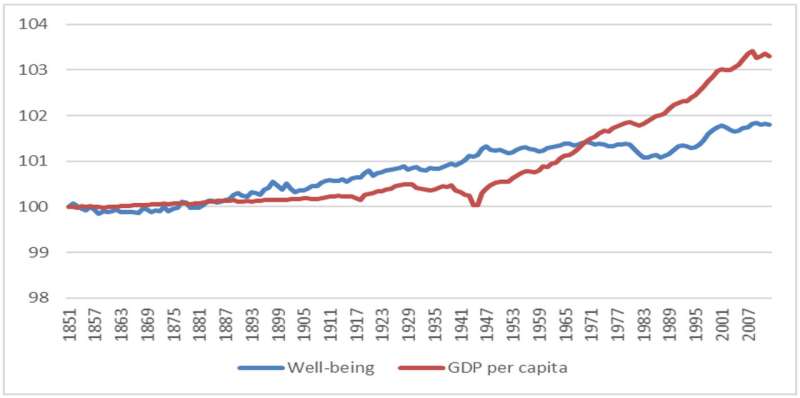

According to Smits, we are dealing with a well-being paradox: People are getting richer, but not more satisfied. This is illustrated in a book he wrote with Harry Lintsen, Frank Veraart and John Grin that will be published shortly. It contains an analysis of wide well-being of the Netherlands, measured from the year 1850. They used 15 indicators and combined them into one indicator followed by a comparison with the development of the gross domestic product per capita. The resulting graph shows that wealth and well-being went more or less hand-in-hand until 1950, after which well-being edged ahead. But then economic growth accelerated solidly, while wide well-being lagged behind.

The model that Smits developed with his colleagues has about 100 indicators to measure well-being, whether societies leave enough for the next generation, and whether they do not make excessive demands on the resources of other countries—often the third world. An example of an indicator is the percentage of people with obesity as a measure of nutritional quality. Life expectancy serves as a measure of health. The level of education is a measure of the human capital of a country. Smits' model looks not only at the national averages, but also at how wealth is divided throughout society. For example, how much do incomes vary? Do women receive as much education as men, and are they equally represented in parliament?

An important precondition for the choice of indicators is that they are universal. Smits says, "You often still see that sustainability policy is a political toy, which is always adjusted when a new government takes office. We therefore want a model that is robust, a model that is above politics." Moreover, the indicators do not have to depend on country or culture, so that they measure what matters everywhere.

The application of the model has already yielded interesting new insights. For example, it appears that global CO2 emissions have already exceeded the standard set out in the Paris Agreement of 2015. The analyses also show that countries that had colonies often still have an excessive claim on raw materials from developing countries, led by former colonial powers the Netherlands and Portugal.

Although there is already a detailed model, there are still many questions that Smits wants to get his teeth into as a professor. One of them is the question of how you measure the value of nature and animals, without looking only at economic value. There is also a great need for an indicator that warns about bubbles in the financial sector, because they repeatedly cause recessions.

More information: For a full overview see the report Conference of European Statisticians Recommendations on Measuring Sustainable Development: www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/st … _SD_web.pdf#page=102

Provided by Eindhoven University of Technology