Consequences of gaps of uprooted or broken trees in Amazonia

Gaps of uprooted or broken trees in Amazonia have cascading consequences, from local farm productivity to global carbon storage. Severe rain or thunderstorms with descending winds, expected to become more frequent with climate change, cause these gaps. For the first time, researchers show how the gaps vary across seasons and years in central Amazonia (Brazil). They found the trees break or fall more often between September and February. They also found that gaps were driven by storms forming in southern Amazonia and moving northeast.

These results will improve representations of tree mortality in Earth system models. In particular, the results will improve the Accelerated Climate Modeling for Energy Land Model. These models help scientists understand how strong storms affect tropical forests. These forests absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and impact the Earth's overall energy balance. Understanding tree death events is important given the increasing occurrences of El Niño events.

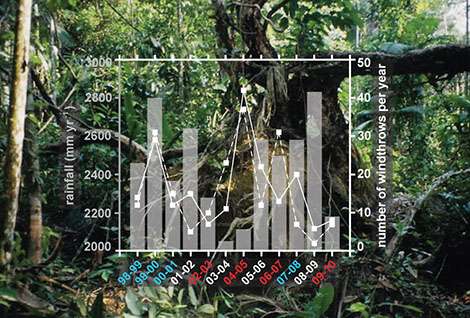

Gaps or broken trees, known as windthrows, are a common form of tree mortality in Amazonia. Windthrows affect forest dynamics and carbon storage, yet how windthrows vary over time has not been investigated. For the first time, researchers measured the seasonal and interannual variability of windthrows, focusing on an area in central Amazonia (Brazil). The team used Landsat images from 1998 through 2010 to detect windthrows, based on their shape and spectral characteristics. They found that windthrows occur every year but were more frequent between September and February. The team found that complex, organized downward rain and thunderstorms embedded in larger systems, such as squall lines, can cause windthrows. Also, they found that southerly squall lines (that move from southwest to northeast) happened more often than previously stated at the ~50-year interval. Looking across years, the team did not find a link between the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and windthrows.

More information: R.I. Negron-Juarez et al. Windthrow Variability in Central Amazonia, Atmosphere (2017). DOI: 10.3390/atmos8020028

Provided by US Department of Energy