A faster, less costly test detects foodborne toxin

One of the most common causes of food poisoning is the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, which produces a wide range of toxins. One of these, staphylococcal enterotoxin type E (SEE), has been associated with outbreaks in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that each year, 1 in 6 Americans—48 million people—get sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die of foodborne diseases. About 240,000 illnesses, 1,000 hospitalizations, and 6 deaths are caused by staphylococcal food poisoning.

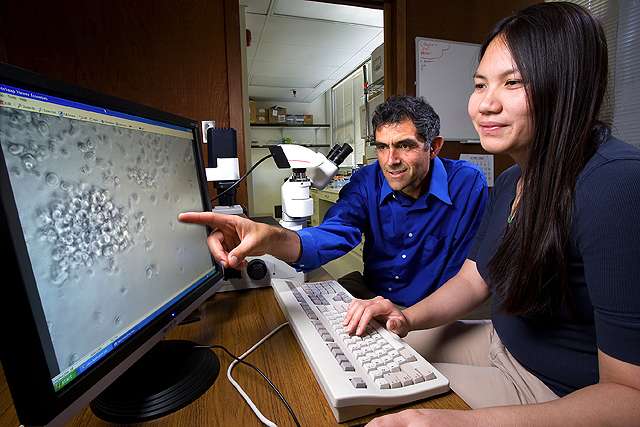

At the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Western Regional Research Center in Albany, California, chemist Reuven Rasooly and his colleagues have developed a less expensive, faster, and more sensitive test to specifically detect SEE in foods. The test uses immune cells called "T-cells."

The current method for detecting these toxins is an animal model. It is expensive, has low sensitivity, and is difficult to reproduce. Other tests are available, but they can't distinguish between active toxin, which poses a threat to public health, and inactive toxin, which does not do so.

"To detect active toxin," says Rasooly, "we used a T-cell line genetically engineered to produce light when exposed to staphylococcal toxin. The light intensity corresponds to the toxin concentration." If the cells are exposed to very low amounts of toxin, they give off very low light intensity. If they are exposed to higher amounts of toxin, light emission and intensity is greater, he explains.

The animal-model test detects active toxin just 50 percent of the time, whereas the new T-cell test detects active toxin 100 percent of the time. "Our test is much more sensitive than the current 'gold standard' animal model or other tests," Rasooly says. In addition, the T-cell test detects toxin within 5 hours, whereas other tests take between 48 and 72 hours.

"This is the most sensitive assay to date for detecting SEE," Rasooly says. "The test can be used by food makers who want to make their products safer before marketing them and by public health officials to trace the source of foodborne outbreaks."

Provided by Agricultural Research Service