Detailed images of Schiaparelli and its descent hardware on Mars

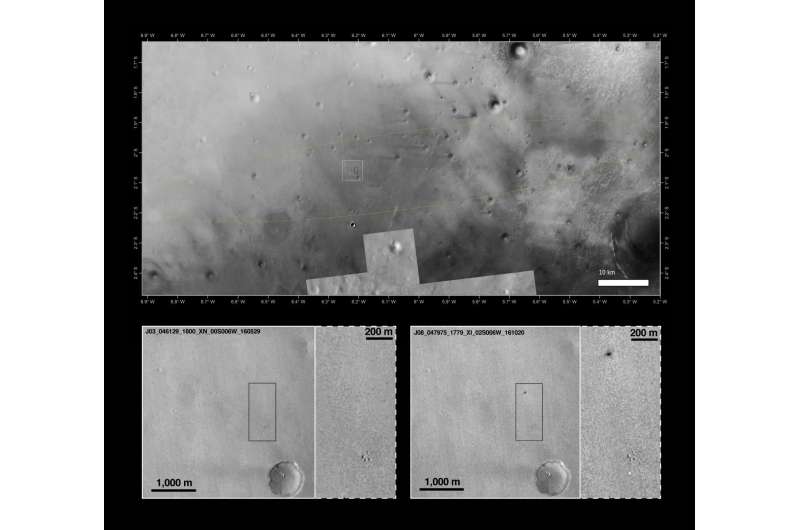

A high-resolution image taken by a NASA Mars orbiter this week reveals further details of the area where the ExoMars Schiaparelli module ended up following its descent on 19 October.

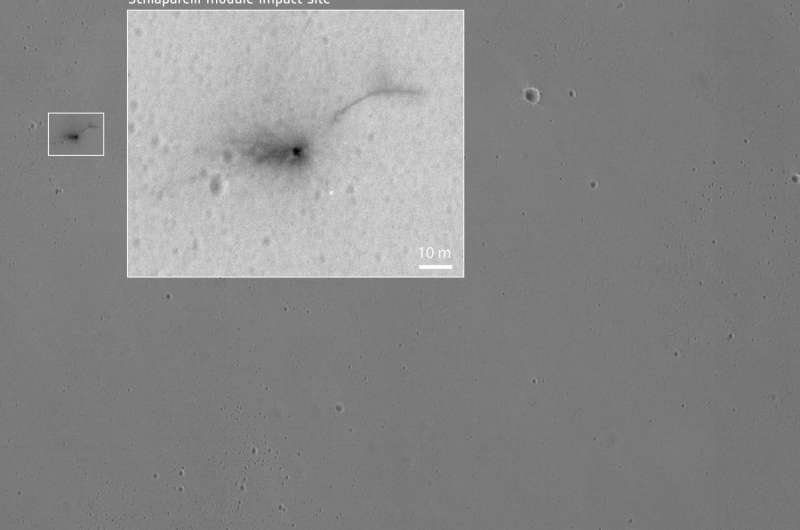

The latest image was taken on 25 October by the high-resolution camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and provides close-ups of new markings on the planet's surface first found by the spacecraft's 'context camera' last week.

Both cameras had already been scheduled to observe the centre of the landing ellipse after the coordinates had been updated following the separation of Schiaparelli from ESA's Trace Gas Orbiter on 16 October. The separation manoeuvre, hypersonic atmospheric entry and parachute phases of Schiaparelli's descent went according to plan, the module ended up within the main camera's footprint, despite problems in the final phase.

The new images provide a more detailed look at the major components of the Schiaparelli hardware used in the descent sequence.

The main feature of the context images was a dark fuzzy patch of roughly 15 x 40 m, associated with the impact of Schiaparelli itself. The high-resolution images show a central dark spot, 2.4 m across, consistent with the crater made by a 300 kg object impacting at a few hundred km/h.

The crater is predicted to be about 50 cm deep and more detail may be visible in future images.

The asymmetric surrounding dark markings are more difficult to interpret. In the case of a meteoroid hitting the surface at 40 000–80 000 km/h, asymmetric debris surrounding a crater would typically point to a low incoming angle, with debris thrown out in the direction of travel.

But Schiaparelli was travelling considerably slower and, according to the normal timeline, should have been descending almost vertically after slowing down during its entry into the atmosphere from the west.

It is possible the hydrazine propellant tanks in the module exploded preferentially in one direction upon impact, throwing debris from the planet's surface in the direction of the blast, but more analysis is needed to explore this idea further

An additional long dark arc is seen to the upper right of the dark patch but is currently unexplained. It may also be linked to the impact and possible explosion.

Finally, there are a few white dots in the image close to the impact site, too small to be properly resolved in this image. These may or may not be related to the impact – they could just be 'noise'. Further imaging may help identify their origin.

Some 1.4 km south of Schiaparelli, a white feature seen in last week's context image is now revealed in more detail. It is confirmed to be the 12 m-diameter parachute used during the second stage of Schiaparelli's descent, after the initial heatshield entry into the atmosphere. Still attached to it, as expected, is the rear heatshield, now clearly seen.

The parachute and rear heatshield were ejected from Schiaparelli earlier than anticipated. Schiaparelli is thought to have fired its thrusters for only a few seconds before falling to the ground from an altitude of 2–4 km and reaching the surface at more than 300 km/h.

In addition to the Schiaparelli impact site and the parachute, a third feature has been confirmed as the front heatshield, which was ejected about four minutes into the six-minute descent, as planned.

The ExoMars and MRO teams identified a dark spot last week's image about 1.4 km east of the impact site and this seemed to be a plausible location for the front heatshield considering the timing and direction of travel following the module's entry.

The mottled bright and dark appearance of this feature is interpreted as reflections from the multilayered thermal insulation that covers the inside of the front heatshield. Further imaging from different angles should be able to confirm this interpretation.

The dark features around the front heatshield are likely from surface dust disturbed during impact.

Additional imaging by MRO is planned in the coming weeks. Based on the current data and observations made after 19 October, this will include images taken under different viewing and lighting conditions, which in turn will use shadows to help determine the local heights of the features and therefore a more conclusive analysis of what the features are.

A full investigation is now underway involving ESA and industry to identify the cause of the problems encountered by Schiaparelli in its final phase. The investigation started as soon as detailed telemetry transmitted by Schiaparelli during its descent had been relayed back to Earth by the Trace Gas Orbiter.

The full set of telemetry has to be processed, correlated and analysed in detail to provide a conclusive picture of Schiaparelli's descent and the causes of the anomaly.

Until this full analysis has been completed, there is a danger of reaching overly simple or even wrong conclusions. For example, the team were initially surprised to see a longer-than-expected 'gap' of two minutes in the telemetry during the peak heating of the module as it entered the atmosphere: this was expected to last up to only one minute. However, further processing has since allowed the team to retrieve half of the 'missing' data, ruling out any problems with this part of the sequence.

The latter stages of the descent sequence, from the jettisoning of the rear shield and parachute, to the activation and early shut-off of the thrusters, are still being explored in detail. A report of the findings of the investigative team is expected no later than mid-November 2016.

The same telemetry is also an extremely valuable output of the Schiaparelli entry, descent and landing demonstration, as was the main purpose of this element of the ExoMars 2016 mission. Measurements were made on both the front and rear shields during entry, the first time that such data have been acquired from the back heatshield of a vehicle entering the martian atmosphere.

The team can also point to successes in the targeting of the module at its separation from the orbiter, the hypersonic atmospheric entry phase, and the parachute deployment at supersonic speeds, and the subsequent slowing of the module.

These and other data will be invaluable input into future lander missions, including the joint European–Russian ExoMars 2020 rover and surface platform.

Finally, the orbiter is working well and being prepared to make its first set of measurements on 20 November to calibrate its science instruments.

Provided by European Space Agency