First photo of planet in making captured

There are 450 light-years between Earth and LkCa15, a young star with a transition disk around it, a cosmic whirling dervish, a birthplace for planets.

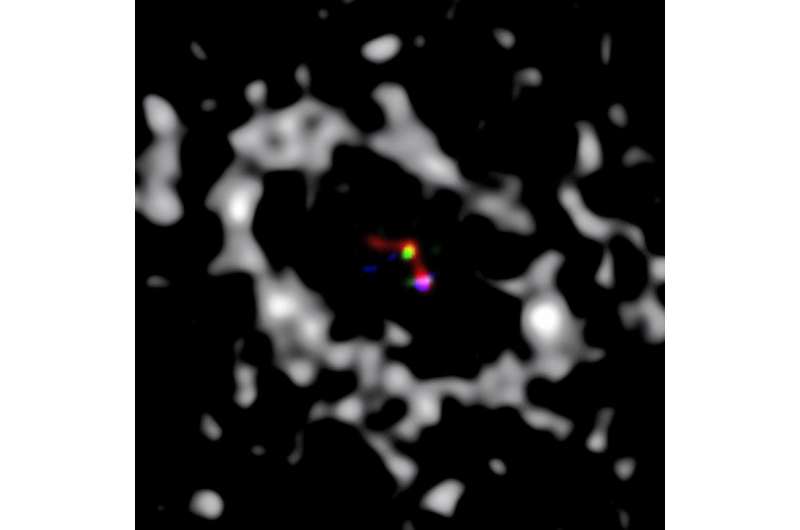

Despite the disk's considerable distance from Earth and its gaseous, dusty atmosphere, University of Arizona researchers captured the first photo of a planet in the making, a planet residing in a gap in LkCa15's disk.

Of the roughly 2,000 known exoplanets—planets that orbit a star other than our sun—only about 10 have been imaged, and that was long after they had formed, not when they were in the making.

"This is the first time that we've imaged a planet that we can say is still forming," says Steph Sallum, a UA graduate student, who with Kate Follette, a former UA graduate student now doing postdoctoral work at Stanford University, led the research.

The researchers' results were published in the Nov. 19 issue of Nature.

Only months ago, Sallum and Follette were working independently, each on her own Ph.D. project. But serendipitously they had set their sights on the same star. Both were observing LkCa15, which is surrounded by a special kind of protoplanetary disk that contains an inner clearing, or gap.

Protoplanetary disks form around young stars using the debris left over from the star's formation. It is suspected that planets then form inside the disk, sweeping up dust and debris as the material falls onto the planets instead of staying in the disk or falling onto the star. A gap is then cleared in which planets can reside.

The researchers' new observations support that view. Sallum says researchers are just now being able to image objects that are close to and much fainter than a nearby star. "That's because of researchers at the University of Arizona who have developed the instruments and techniques that make that difficult observation possible," she says.

Those instruments include the Large Binocular Telescope, or LBT, the world's largest telescope, located on Arizona's Mount Graham, and the UA's Magellan Telescope and its Adaptive Optics System, MagAO, located in Chile.

Capturing sharp images of distant objects is difficult thanks in large part to atmospheric turbulence, the mixing of hot and cold air.

"When you look through the Earth's atmosphere, what you're seeing is cold and hot air mixing in a turbulent way that makes stars shimmer," says Laird Close, UA astronomy professor and Follette's graduate adviser.

"To a big telescope, it's a fairly dramatic thing. You see a horrible-looking image, but it's the same phenomenon that makes city lights and stars twinkle."

Josh Eisner, UA astronomy professor and Sallum's graduate adviser, says big telescopes "always suffer from this type of thing." But by using the LBT adaptive optics system and a novel imaging technique, he and Sallum succeeded in getting the crispest infrared images yet of LkCa15.

Meanwhile, Close and Follette used Magellan's adaptive optics system MagAO to independently corroborate Eisner and Sallum's planetary findings.

"Results like this have only been made possible with the application of a lot of very advanced new technology to the business of imaging the stars," says professor Peter Tuthill of the University of Sydney and one of the study's co-authors, "and it's really great to see them yielding such impressive results."

More information: S. Sallum et al. Accreting protoplanets in the LkCa 15 transition disk, Nature (2015). DOI: 10.1038/nature15761

Journal information: Nature

Provided by University of Arizona