The ethical slipperiness of hoaxes

Hoaxes sure can stir up a lot of emotion, can't they? We tend to have a quick reaction to them, and they flush out differences in values quickly, too.

A few days ago, American journalist John Bohannon wanted to make a big splash with a post titled, "I fooled millions into thinking chocolate helps weight loss. Here's how".

It's part of a publicity campaign started by two German journalists co-producing a documentary with a major public TV broadcaster. It's a takedown of the diet industry, set to air next weekend in Germany.

As hoaxes go, this one is particularly complicated. And "hoax" is a pretty slippery concept, anyway.

At one extreme of a very broad spectrum, a hoax can be a straight-up crime – like fraud, and scams to swindle people out of money. Police "stings" hover towards this end of the spectrum, because they can veer into the crime of entrapment. (There's debate about whether stings are as effective as other policing approaches, and whether they have only a very short-term effect or might increase crime.)

Way down the other end of the spectrum, a hoax can be a parody or performance art that's snuck into the mainstream with just enough ambiguity that some people don't realize it's not "real". It might be intending to jolt awareness, educate, or draw attention to ideas or a point of view. It's not really intending to deceive.

This chocolate hoax is still unfolding, so we can't have any idea where on the spectrum of seriousness or impact it's going to land. We have been reacting to bits of a very stage-managed picture.

So far, the journalists have told us some details about four components:

- creating a website with an address and contact point for a fictitious research institute (in Germany);

- a real study (in Germany) on chocolate and weight loss designed to be rubbish science that would all but guarantee statistical artifacts that were marketable and misleading;

- a pseudoscientific article with authors' names altered, claiming to show chocolate is a "weight-loss accelerator" in an English journal (pulled offline by the journal in the last few days, but available here); and

- a press campaign touting the study to bait journalists into covering it, including paying for testimonials.

Before we get to it, though, because it involves a genuine randomized trial, let's look at what governs the conduct of this kind of research in Germany. Frameworks vary a lot internationally, even regionally. (Michelle Meyer, from Harvard Law School, has written a very interesting blog post on this hoax, from the perspective of the rules that would have applied if they'd done it in the US instead.)

According to Bohannon, the trial was "run" by a doctor (here and here). Doctors are in a particular position of power and trust, with their patients, and in society. As long as they are acting in a medical capacity with an individual, they have considerable freedom.

However, when there's an inherent possibility that another interest has the potential to come before the interests of the individual, then their wings may be clipped.

One of those areas is doctors doing human research. That's not to say that research is always inherently against the individual's interests. Just that the new dimension changes the "social contract". It's a position I've long agreed with, although many don't.

In Germany, if a doctor (or certain others) is going to do research in people that might affect their mental or physical health, or with identifiable data, she or he must first lodge an application to an ethics committee. That details the study plan, numbers of patients, issues around privacy and data handling, how people will be indemnified against harm, and so on. There are additional research areas where this is needed, but that's not relevant here.

With a non-drug study outside a university, the ethics committee responsible is from a state medical board like this one (called a "chamber"). German legislation makes the international Declaration of Helsinki binding for doctors too. (There are summaries of the German arrangement in English here [PDF] and in the background of this article.)

In this interview with Bohannon, he said there was no submission for ethical review. There's been no public statement from anyone else involved on this question that I could find by internet searching in both German and English. There's been no reply to at least one email to the doctor he says "ran" the trial. On the 28th, NPR reported asking Bohannon a follow-up question about ethics, but no answer has been reported yet.

While hoping for the best at the moment, it's disturbing. I've seen a lot of "oh it doesn't matter – it's just about eating chocolate!" in people's comments, but others are also expressing grave concern. Maybe there is nothing to worry about: but I'd very much like to know that someone other than the participants ensured that was so.

Here's how Bohannon and the two German journalists whose project this is, Diana Löbl and Peter Onneken, have described what happened. You can see Löbl and Onneken in action here in this short clip (warning, it's disrespectful of overweight people to say the least).

Löbl and Onneken wanted to "reveal the corruption of the diet research-media complex by taking part", according to Bohannon. They approached a medical scientist for advice about how you would do a scientifically rigorous trial, so they could make sure, she says, that they did the opposite.

Bohannon was called by the pair in December 2014, and then Löbl and Onneken "used Facebook to recruit subjects around Frankfurt, offering 150 Euros to anyone willing to go on a diet for 3 weeks. They made it clear that this was part of a documentary film about dieting, but they didn't give more detail" (according to Bohannon). According to Löbl, she and Onneken did the recruiting, wearing white coats – because "clothes make the person", she said – when they recruited 16 people in January.

When researchers intend to deceive people about the real purpose of a study, there are additional ethical hurdles. They are expected to justify why they can't be told the truth. And to demonstrate there's a potential for benefit that outweighs the burdens of inconvenience and potential harm people will be signing up for under false pretenses.

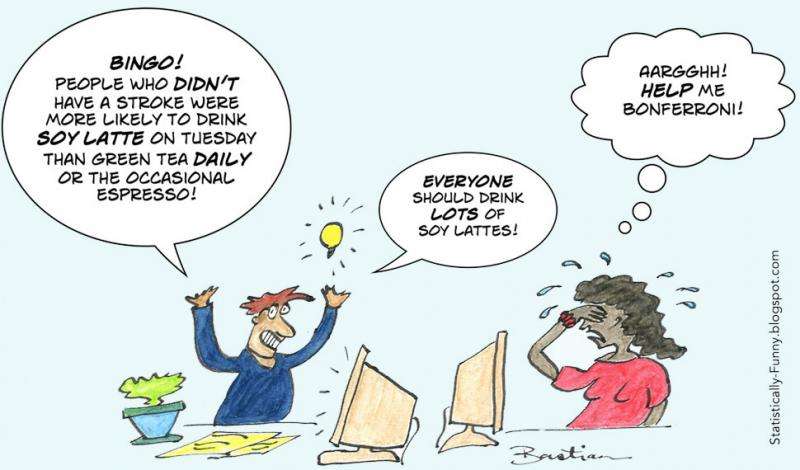

Well, there were no benefits to accrue from the study itself for the participants: when the ones who had to change to a "low carb" diet (2 out of 3 of the groups) had to eat more of this and less of that that every day, when they were all getting their blood tested, taking urine samples every day for weeks, logging their sleeping, eating, moods etc every day – the data could never advance knowledge about dieting. Here's an old post of mine on the risks of multiple testing. Each time you test, you run a small risk of striking a data anomaly. But the more you hunt, the more this risk snowballs.

The study couldn't tell us anything we don't already know about its true objective either, the diet research industry and journalism. We already know how easy it is to publish bad science, and that there's low quality journalism. And actually, comparatively few journalists fell for it.

If you're going to deceive people, you have an ethical obligation about how you reveal the deception to them afterwards. That's the subject of the question NPR has posed to Bohannon: just how are the 16 people finding out they were duped, if that's what happened? (Here's hoping it's not by first seeing that YouTube clip.)

So was the study ethical or wasn't it? One of the reasons many researchers feel very negative about these ethical review systems is that there's often no consistency in the answers people come to on these questions. Meyer's post goes into this important point in some depth. Maria Godoy's report at NPR found contradictory opinions here too.

My personal position is that if we don't agree with current standards for professional and ethical conduct, we can try to change the system, but we have to abide by it. If the standards are too low, we should aim higher – but we shouldn't do less than is expected of us. To not do so is a serious breach. And we can't afford to erode public trust in doctors and health care professionals who approach people to participate in clinical trials.

The argument in favor of this hoax is that it will have a benefit in terms of better journalism and perhaps even statistical literacy for enough members of the public to make it justifiable. Gary Schwitzer wrote: "I don't know if Bohannon's latest stunt will have any positive impact. Journalists and bloggers have already moved on to the next, much-quicker-than-24-hour, news cycle." Meyer wrote: "What we need are feasible solutions to make these groups aware of this problem, not more evidence of the problem that perversely contributes to the problem itself."

I agree with both of them. And there is some data to back that point of view: the real obstacles to better reporting are issues that won't be affected by this, and even intensive training may not change behavior. Anyway, education has moved on from models based on shaming.

For what it's worth, as a blogger who plugs away at statistical literacy writing and cartooning, I didn't find the interest in reading my relevant posts as high as it gets when a media story challenges something people actually believed. (Last year's spate of interest in resveratrol, for example.)

Faye Flam questions the grandiosity of Bohannon's "I fooled millions" claim:

Unless there was a suspicious spike in chocolate sales, it seems more likely that most people said "meh" or maybe even "huh?" but did not rush out to start a chocolate diet. For all we know from the evidence presented, 27 Americans were fooled. Bohannon's claim plays to one of the most common and powerful biases – The desire to believe we're smarter than other people. I'd never heard of the original study, but the exposure of the hoax is causing delight among my Facebook friends. People can't resist reading about all those millions of inferior thinkers. Perhaps Mr. Bohannon fooled millions, or perhaps he fooled himself.

This gets us to the next slippery issue about this hoax: the journalists' side. I think on balance the world's journalists don't get such a bad grade in terms of jumping to the string-pulling of the first campaign. But I wouldn't give them high marks for their coverage this week.

First time around, the trio got some journalists from the infotainment end of the industry to dance the tune. This time, they're getting the high end of th

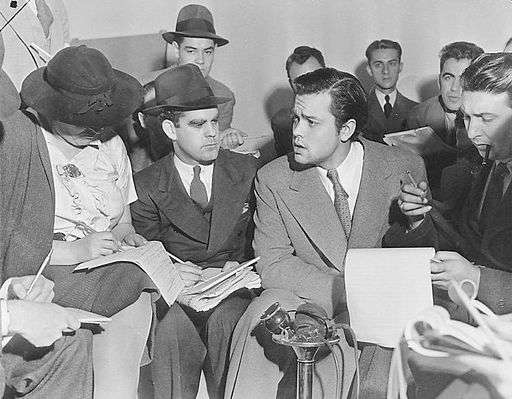

Hoaxing and the American press is the subject of a dissertation by Mario Castagnaro. It's a fascinating look at the way the community's attitude to hoaxes and journalists' roles changed across several decades.

One of the things that struck me was that many see journalists' hoaxes as a clever assault on the powerful. Yet, the more common hallmarks of the genre may be the ego and ambition of hoaxers – along with underlying disrespect for the public and other journalists.

Orson Welles' famous War of the Worlds radio broadcast in 1938 was a cultural touchstone – and an unusually well-studied hoax. A revealing Welles' quote relevant to his willingness to intentionally cause distress to bolster his career stood out for me: "I didn't go to jail. I went to Hollywood." Castagnaro singles it out as one of the turning points for society becoming more critical of hoaxes in the media – and expecting journalists to expose hoaxes, not undertake them. It was, he argues, key to the professionalization of journalism.

Clifford Irving's Howard Hughes biography hoax in the early 1970s was another, changing direction from more gonzo journalism that had begun to encourage sensationalism, ego trips, and little regard for "objective distance" between the journalist and subject. (Irving did go to jail, because his hoax involved perjury and larceny.) Over time, hoaxing in journalism, Castagnaro argues, "came to be more readily associated with manipulation and the distortion of 'truth'…a dangerous betrayal of public trust."

I'm a cartoonist, so it's no surprise that I am a big fan of parody and satire as a vehicle to communicate ideas. I don't think there's a fundamental breach of public trust there. Sure, occasionally people "fall" for an Onion story, but that's not an abuse of power and a position of trust. We really need journalists to know the difference, and to call out abuses of power – not generate them.

Provided by Public Library of Science