Unique floating lab showcases 'aliens of the sea'

Researcher Leonid Moroz emerges from a dive off the Florida Keys and gleefully displays a plastic bag holding a creature that shimmers like an opal in the seawater.

This translucent animal and its similarly strange cousins are food for science. They regrow with amazing speed if they get chopped up. Some even regenerate a rudimentary brain.

"Meet the aliens of the sea," the neurobiologist at the University of Florida says with a huge grin.

They're headed for his unique floating laboratory.

Moroz is on a quest to decode the genomic blueprints of fragile marine life, like these mysterious comb jellies, in real time—on board the ship where they were caught—so he can learn which genes switch on and off as the animals perform such tasks as regeneration.

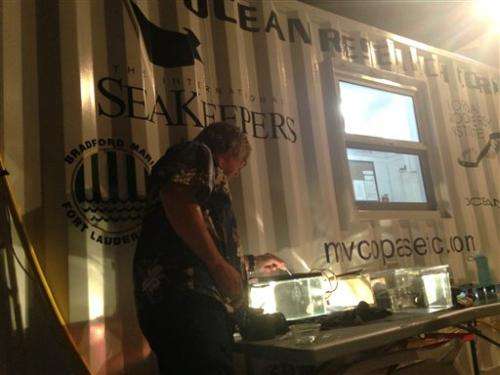

No white coats needed here. The lab is a specially retrofitted steel shipping container, able to be lifted by crane onto any ship Moroz can recruit for a scientific adventure.

Inside, researchers in flip-flops operate a state-of-the-art genomic sequencing machine secured to a tilting tabletop that bobs with rough waves. Genetic data is beamed via satellite to a supercomputer at the University of Florida, which analyzes the results in a few hours and sends them back.

The work is part conservation.

"Life came from the oceans," Moroz says, bemoaning the extinction of species before scientists even catalog all of them.

Surprising as it may sound, it's part brain science.

"We cannot regenerate our brain, our spinal cord or efficiently heal wounds without scars," Moroz notes.

But some simple sea creatures can.

Moroz accidentally cuts off part of a comb jelly's flowing lower lobe. By the next afternoon, it had begun to regrow.

What's more remarkable, these gelatinous animals have neurons, or nerve cells, connected in circuitry that Moroz describes as an elementary brain. Injure those neural networks and some but not all comb jelly species can regenerate them in three days to five days, he said.

"We need to learn how they do it. But they are so fragile, we have to do it here," at sea, he says.

In two trial-run sails off the coast of Florida, Moroz's team generated information about thousands of genes in 22 organisms. Moroz's ultimate goal is to take the project around the world, to remote seas where it's especially hard to preserve marine animals for study.

"If the sea can't come to the lab, the lab must come to the sea," says Moroz, who invited The Associated Press on the second test trip, a 2½-day sail.

___

Flying fish zip alongside the 141-foot (43-meter) yacht Copasetic as it bounces across the giant ocean current known as the Gulf Stream. Inside the lab, the donated $50,000 genetic sequencer is rocking on its special tabletop.

Molecular biologist Andrea Kohn wedges her hip against cabinets to stay upright. With a pipette in hand, she carefully drips precious samples from a comb jelly experiment onto a chip the size of a digital camera's memory card.

Graduate student Rachel Sanford had cut some of these animals, and then biopsied the healing tissue 30 minutes, an hour and two hours later. She studies the comb jellies' rudimentary brains in much the same way, looking for master regulators, key molecules that control regrowth.

If she can find some, a logical next question is whether people harbor anything similar that might point to pathways important in spinal cord or brain injuries.

The lab was born of frustration, after Moroz kept shipping samples home that arrived too degraded for genetic research.

The pieces fell into place when a University of Florida alumnus lent them his boat for the trial runs. Then, the Copasetic's captain noted that a shipping container like those used by freighters would fit on the main deck.

The nonprofit Florida Biodiversity Institute found one for sale, welded in windows and installed lab fixtures. The team was off.

_____

Oceanography and brains may seem to be strange bedfellows. But much of what scientists know about how human neurons and synapses, their connections, form memories came from studying large green sea slugs like the one graduate student Emily Dabe gently cups in her hand.

Human brains have 86 billion neurons, give or take. Sea slugs have only about 10,000, large neurons grouped into clusters rather than a central brain, Dabe explains while dissecting the easy-to-spot cells. She brought the animal on board as a control for comb-jelly experiments.

Yet scientists can condition sea slugs, with mild shocks, to study that type of memory, Dabe says. A bit further up the neural ladder, the octopus has about 500 million neurons, says graduate student Gabrielle Winters. There are reports of them learning by watching, although Moroz cautions that's highly controversial.

The question is how multiple genes work together for increasingly complex memories. That requires working with simple creatures, which share certain genetic pathways with people, says University of Washington biology professor Billie Swalla, who is watching Moroz's project with interest.

Moroz compares the genetic interactions to learning grammar: Knowing DNA is like knowing the alphabet and some words, but not how they're strung together to make a sentence.

"We need to know how to orchestrate the grammar of the brain," he says.

_____

Outside on deck, it's suddenly like Christmas.

Moroz and Gustav Paulay, a curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History, are back from a dive bearing gifts for the lab: clear jars and plastic bags teeming with invertebrates.

"Oh my god, you have to see this one," Paulay says, entranced by a rare flat, see-through snail, pink ribbons snaking through its shell-free body.

But the catch of this day is the collection of comb jellies, officially named ctenophores. (Don't pronounce the silent "c''.) Named for the comb-like rows of hair they use to swim, the ctenophores refract light so it looks like they flash electric through the water. The one that shimmered like an opal is a little bigger than a golf ball.

Another is light pink, flat and shaped like a delicate sack. This one's a hungry predator. It swallows whole its larger, rounded cousin.

A tiny, hot pink version zips through the water—it looks like a new species, Moroz says.

Some ctenophores regenerate that elementary brain and some, like that hungry sack-shaped Beroe, don't. Some use more muscles to swim. Some have tentacles to catch their food, instead of the Beroe's stretchy mouth.

Moroz muses on the diversity: "Tell me honestly, why do we study rats?"

© 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.