Setting sight on a single star

NASA recently selected 20 small satellites to fly as auxiliary cargo aboard rockets that are planned to launch in 2011 and 2012.

These small “CubeSats” are nanosatellites, measuring approximately four inches long, with a volume of about one quart, and weighing 2.2 pounds or less.

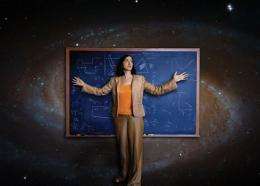

Among the missions selected is ExoPlanetSat, a telescope designed to search for planets orbiting distant stars. Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT, is the principal investigator on the project.

The ExoPlanetSat will monitor a single star in the hopes of finding an Earth-like planet in orbit around it.

The telescope will be on the lookout for a transit, an eclipse-like event when a planet moves across the face of a star. A transit causes the total light emitted from a star to drop briefly before it returns to its full radiance. An Earth-like planet passing in front of a far-distant star would cause the light to drop only about one-hundredth of one percent.

Although that’s a minuscule drop in the total light emitted by a star, it’s still enough for a telescope to detect -- as long as the control system keeps the telescope’s gaze steady. The telescope’s CCD imaging system has to be able to focus on the star continuously, but a variety of forces – Earth’s gravity, its magnetic field, its atmospheric drag – will conspire to push the telescope out of alignment. It will be the control system’s job to push back, tilting its CCD mere microns at a time to keep it from drifting off-target.

Seager says that the current ExoPlanetSat concept is to search for transits for planets that are already known to exist from radial velocity detections. The radial velocity method looks for a shift in a star’s light, an indication of a gravitational dance taking place between the star and a planet.

“Right now our favorite star is Alpha Centauri,” says Seager. Although to the unaided eye Alpha Centauri looks like a single star, it actually is a binary system -- Alpha Centauri A is larger and brighter than Alpha Centauri B. Each star could have their own planets, or planets could orbit the binary system. Since both stars are fairly similar to the Sun in age and metallicity, different planet-hunting teams have targeted the system but so far have not found massive gas giants like Jupiter orbiting there. However, computer models suggest the system should have Earth-like terrestrial planets.

Seager hopes to eventually launch a fleet of dozens of Earth-hunting telescopes, each one dedicated to watching a different star.

Once Earth-like planets are found, scientists may be able to figure out if they are inhabited by deducing their atmospheres. Knowing whether a planet has oxygen, for instance, would indicate that the planet may have oxygen-producing organisms on it similar to life on Earth.

The design of ExoPlanetSat was developed under a NASA ASTID (Astrobiology Science and Technology for Instrument Development) grant. "We are really succeeding in a huge way, and it is all thanks to the NASA ASTID seed funding for our concept study,” says Seager. The current project is supported by MIT and the Draper Laboratory.

Source: Astrobio.net