Aquatic carnivorous plants with ultra-fast traps studied

How do Utricularia, aquatic carnivorous plants commonly found in marshes, manage to capture their preys in less than a millisecond? A team of French physicists from the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire de Physique has identified the ingenious mechanical process that enables the plant to ensnare any small, a little too curious aquatic animals that venture too closely. It is the reversal of its curvature and the release of the associated elastic energy that make it the fastest known aquatic trap in the world. These results are published on 16 February 2011 on the website of the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B.

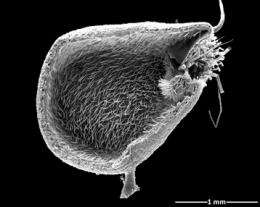

Utricularia are carnivorous plants that capture small prey with remarkable suction traps. Utricularia are rootless plants formed of very thin, forked leaves on which wineskin-shaped traps, just a few millimeters in size, are attached. Only the flowers, standing on long stems, stick out of the water. The traps are underwater. When an aquatic animal (water fleas, cyclops, daphnia or small mosquito larvae) touches its sensitive hairs, the trap sucks it in, in a fraction of a second, along with water, which is then drained through its walls.

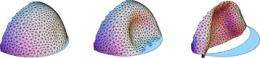

In order to understand the mechanical process involved, the researchers observed and recorded the extremely rapid movements of the capture phase with a high speed camera. The scientists show that the trap door buckles, which reverses its curvature and allows it to open and close very rapidly, thus entrapping its prey. The suction time (less than a millisecond) is much shorter than was previously assumed.

How exactly does this implacable trap operate mechanically? In the first stage, which lasts several hours, the plant slowly pumps out the liquid it contains, thus placing the trap under negative pressure. During this arming phase, elastic energy is stored in the trap walls. The trap is ready to close on its prey. The slightest touch on a sensitive hair attached to the trap door triggers its opening. This begins with the "buckling" of the trap door, in other words a sudden change in shape. The trap door thus acts like an elastic valve: initially bulging outwards, it turns inwards, reversing its curvature.

The release of the elastic energy stored in the trap walls then create a suction vortex, with accelerations up to 600 g, leaving the prey that has set off the mechanism little chance of escape. Then, very rapidly, the trap door reverses again and returns to its initial shape. The trap is then hermetically closed around its prey, which will be dissolved by the plant's digestive enzymes, providing it with precious nutrients. Until its next capture...

These results, observed with a high-speed camera, have also been confirmed by the researchers' numerical simulations, which will be published in a second article in Physical Review E.

More information: This work will be published in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B (Biological sciences), in the press (2011), "Ultra-fast underwater suction traps" O. Vincent, C. et al. The numerical model of the trap will be published in Physical Review E, in the press (2011) "Mechanical model of the ultra-fast underwater trap of Utricularia" by M. Joyeux, et al.

Provided by CNRS