March 26, 2010 feature

Probing the magnetic properties of solid oxygen

(PhysOrg.com) -- "Many scientists, like me, have an interest in the simplest molecules," Stefan Klotz tells PhysOrg.com. "These simple molecules, like water, nitrogen and oxygen, are in quite of the lot of stuff around us, and are abundant in space. There is a lot we could learn about them and their properties, and how the universe works, through study."

Klotz is a scientist at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris, France. He is interested in the way that simple molecules behave under extreme conditions, especially high pressures. “We think of water as a liquid, of course, but many simple molecules and elements, like oxygen, helium and nitrogen, are things we think of as gases. Under high pressure they become solid, and then they are very interesting.”

Working with Cornelius and Philippe, also in Paris, and with Strässle from the ETH Zurich and Paul Scherrer Institut in Switzerland, and Hansen from the Institut Laue Langevin in Grenoble, France, Klotz helped probe the magnetic properties of oxygen in one of its solid forms, showing the magnetic ordering of this elemental molecule. The team's work can be found in Physical Review Letters: “Magnetic Ordering in Solid Oxygen up to Room Temperature.”

In order to look at the magnetic properties of solid oxygen, the team made use of a high pressure device to “squeeze” the oxygen from a gas form into a solid. Klotz is an expert in high pressure techniques, studying the properties of molecules under pressures of up to 100,000 atmospheres. “We have developed a laboratory device that can generate a great deal of pressure, in this case squeezing any material up to between 60,000 and 80,000 atmospheres,” Klotz says.

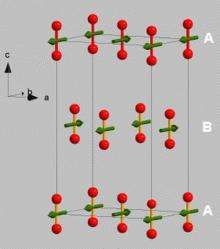

For a system like oxygen, that most people know as a gas, the idea of magnetic ordering is exciting. “As we bring the atoms closer and closer with the pressure, and they feel the interaction with each other, they begin to line up. We cool the whole system so the atoms wobble less and less,” Klotz says. “Normally, in a gas or liquid, the spins are changing direction all of the time. There is no magnetic order, and you can never form a macroscopic magnet.”

However, after being subjected to intense pressure and converted to a solid, oxygen begins to act differently. “All of the spins point in the same direction, creating the effect of having a tiny magnet. This is an exotic phenomenon for a system that most people understand as a gas.” Klotz and his peers ended up with a rather small powder-like substance after putting the oxygen through the process, but it was enough for study. “At such high pressures, the sample size is very small, but it is sufficient to find out what we want to know using the technique of neutron scattering.”

In order to probe the magnetic properties of the solid oxygen sample, the team used neutrons from a research reactor. “We get a beam of the neutrons, and project it on to the sample of solid oxygen inside the pressure cell,” Klotz explains. “The neutrons are deviated, scattering in a specific way. This tells us where the atoms are, and where their magnetic moments point to.”

Klotz believes that this experiment will likely provide information on the fundamental properties of magnets and of oxygen. “Our discovery doesn’t immediately lead to better cell phones, but it is fundamental in nature,” he says. “We have discovered one of the simplest magnets - a single element - without a complex electronic structure. This discovery should contribute to the study of magnets in general, and could eventually lead to the construction of better magnets for technical applications.”

More information: S. Klotz, Th. Strässle, A.L. Cornelius, J. Phillipe, and Th. Hansen, “Magnetic Ordering in Solid Oxygen up to Room Temperature,” Physical Review Letters (2010). Available online: link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.115501

Copyright 2010 PhysOrg.com.

All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of PhysOrg.com.