May You Stay Forever Young

Before plastic surgery and botox, an ancient culture had a different way of dealing with the quest for eternal youth. Why not simply live forever? In medieval China, third century B.C., people believed it possible to be 800 years old, only without the pesky wrinkles and liver spots.

Transcendents were deathless, godlike beings with supernormal powers. They not only had eternal life, people believed they could fly, heal the sick, be in several places at once, predict the future, read thoughts, disappear — and do it all with a youthful glow.

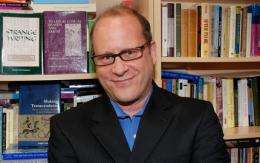

"Human beings have a universal fear of death," said Robert Campany, chair and professor of religion in USC College, who has written two books on transcendents. "Just on that basis, you can understand why one would want the ability to live forever. Plus, these individuals were healers and had strange and mysterious powers."

Campany’s Making Transcendents: Ascetics and Social Memory in Early Medieval China (University of Hawai’i Press, 2009) was published in February. His book, To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong’s Traditions of Divine Transcendents (University of California Press, 2002) was the first complete, critical study of this important, little-known Chinese belief.

Researching ancient Chinese religions was not something Campany expected to pursue as a philosophy major at Davidson College in North Carolina. After earning his bachelor’s, he won a Fulbright scholarship to study reformation history in Germany. He was also offered a Luce scholarship to study in Taiwan for a year. He turned down the Fulbright.

“I thought it would be good for me to learn about another part of the world and to study a little Chinese,” said Campany, also a professor of East Asian languages and cultures now fluent in Chinese. “I never looked back.”

In Taiwan, a Daoist temple piqued his interest: “I had absolutely no idea what happened in there.” He quickly learned. Although he spoke Mandarin, he didn’t understand the Taiwanese style, so he watched the activity inside the temple.

“Not speaking the language is an interesting way to study an unfamiliar culture,” he said. “You can learn a lot about a religion by just observing.”

What he stumbled upon was an elaborate ritual for the dead. A family was told that the reason for its dysfunction stemmed from a dead relative with unfinished business. So family members went to the temple, where a priest in meditation traveled to the otherworld, submitted all necessary paper work for his mission, located the lost soul, bribed its demons with cash, cut the prison doors, and released the relative’s spirit.

A medium then channeled the ancestor who unleashed his grievances.

“There was a lot of crying and airing of old resentments,” Campany said. “It’s almost like group therapy. After that experience, I got interested. I kept studying Chinese and Chinese religions.”

Campany earned his master’s and Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. He taught at Indiana University before joining the College in 2006.

His fascinating tales of travel provide a launching pad for discussing complex concepts in the classroom.

“I think stories are a way into a religious mental world that is much more immediate than if I tried to explain general abstract concepts,” Campany said. “If I just explain the concept of non-duality or the concept of Tao, students can get sort of lost. But everybody can understand a story. Then you can talk about its implications.”

His students analyze old Chinese documents translated into English, rather than rely solely on textbooks’ analyses.

"I’m not criticizing textbooks," he said. “But students don’t need me or someone else spelling out the basic concepts of a certain religion. They can discover that themselves. It’s empowering for students to realize that they can think like a professional scholar.”

In his research on transcendents, Campany looks at how and why many thousands in medieval China believed it possible for individuals to disappear into the mountains alone and return as godlike eccentrics.

“People flocked to these figures,” Campany said. “They would rush to the house where one was staying to try to see them, speak to them.”

In that time, people believed deaths could be staged by transcendents to fool the gods into forgetting to snatch them on their predestined days of death.

If the spirits could be eluded, they thought, maybe so could death. In present day, the concept certainly would have appeal but society is too scientifically savvy to buy into it, Campany said.

Although, imagine the money saved on botox injections.

Provided by University of Southern California (news : web)