Curbing coal emissions alone might avert climate danger, say researchers

An ongoing rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide from burning of fossil fuels might be kept below harmful levels if emissions from coal are phased out within the next few decades, say researchers. They say that less plentiful oil and gas should be used sparingly as well, but that far greater supplies of coal mean that it must be the main target of reductions. Their study appears in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles.

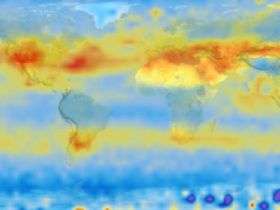

The burning of fossil fuels accounts for about 80 percent of the rise of atmospheric CO2 since the pre-industrial era, to its current level of 385 parts per million. However, while there are huge amounts of coal left, predictions about when and how oil and gas production might start running out have proved controversial, and this has made it difficult to anticipate future emissions. To better understand how the emissions might change in the future, climatologist Pushker Kharecha and director James Hansen of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies—a member of Columbia University's Earth Institute--considered a wide range of scenarios.

"This is the first paper that explicitly melds the two vital issues of global peak oil production and human-induced climate change," Kharecha said. "We found that because coal is much more plentiful than oil or gas, reducing coal emissions is absolutely essential to avoid dangerous climate change." Kharecha is also author of a related article, "How Will the End of Cheap Oil Affect Future Global Climate?"

CO2, which accounts for about half of the human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, concerns scientists because it can remain for centuries. Hansen's previous research suggests that a dangerous level of global warming may occur if CO2 exceeds a concentration of about 450 parts per million. That is a 61 percent increase from the pre-industrial level of 280 parts per million, but only 17 percent more than the current level. Hansen says the danger level would bring a rise of about 1.8°F above the 2000 global temperature. At or beyond this point, disintegration of the West Antarctic ice sheet and Arctic sea ice could reach tipping points, and set in motion feedback mechanisms that would lead to further, accelerated melting.

To better understand the possible trajectory of future CO2, Kharecha and Hansen devised five emissions scenarios spanning the years 1850 to 2100. Each reflects a different estimate for the global production peak of fossil fuels, the timing of which depends on reserve size, recoverability and available technology. "Even if we assume high-end estimates and unconstrained emissions from conventional oil and gas, we find that these fuels alone are not abundant enough to take carbon dioxide above 450 parts per million," Kharecha said.

The first scenario estimates CO2 levels if emissions from fossil fuels follow "business as usual," growing 2 percent annually until half of each reservoir has been recovered. After this, emissions begin to decline by 2 percent annually. In the second scenario, emissions from coal are reduced, first by developed countries starting in 2013, and then by developing countries a decade later, leading to a global phaseout of emissions by 2050. The phaseout could come either from reducing coal consumption or by capturing and trapping CO2 from coal burning before it reaches the air.

The remaining three scenarios include the phaseout of coal, but consider different scenarios for oil use and supply. One case considers a delay in the oil peak by about 21 years to 2037. Another considers fewer-than-expected additions to currently proven reserves, or taxes on emissions that makes fuels too expensive to extract. The final scenario looks at emissions from oil fields that peak at different times, extending the peak into a plateau that lasts from 2020-2040.

The team used a mathematical model to convert CO2 emissions from each scenario into estimates of future concentrations in the atmosphere. The "business as usual" scenario resulted in CO2 that would exceed 450 parts per million from by 2035, and climb to more than double the pre-industrial level. Even when low-end estimates of reserves were assumed, the threshold was exceeded from about 2050 onwards. However, the other four scenarios resulted in CO2 levels that peaked in various years, but all fell below the prescribed cap of 450 parts per million by about 2080 at the latest. Levels in two of the scenarios always stayed below the threshold.

The researchers say that the results clearly imply that emissions from coal should be reduced. This would apply also, they say, to "unconventional" fuels not yet in mainstream use, such as methane hydrates and tar sands. These also contain far more fossil carbon than conventional oil and gas, and thus could potentially be major contributors to emissions.

"We're illustrating the types of action needed to get to target carbon dioxide levels," Kharecha said. "The most important mitigation strategy we recommend—a phase-out of carbon dioxide emissions from coal within the next few decades—is feasible using current or near-term technologies."

The article "How will the end of cheap oil affect future global climate?" is at: www.giss.nasa.gov/research/briefs/kharecha_01/

Source: The Earth Institute at Columbia University