How to Rip a Fluid

In a simple experiment on a mixture of water, surfactant (soap), and an organic salt, two researchers working in the Pritchard Laboratories at Penn State have shown that a rigid object like a knife passes through the mixture at slow speeds as if it were a liquid, but rips it up as if it were a rubbery solid when the knife moves rapidly.

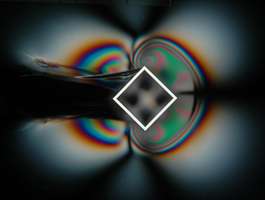

The mixture they study shares properties of many everyday materials -- like toothpaste, saliva, blood, and cell cytoplasm -- which do not fall into the standard textbook cases of solid, liquid, or gas. Instead, these "viscoelastic" materials can have the viscous behavior of a fluid or the elastic behavior of a solid, depending on the situation. The results of these experiments, which are published in the current issue of the journal Physical Review Letters and are featured on its cover, provide new insights into how such materials switch over from being solid-like to being liquid-like.

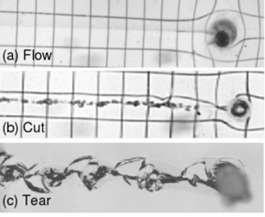

"As a child will swish its finger through an unknown liquid to find out what it is, we built an experiment to pull a cylinder through this viscoelastic material, to learn how it responds," explains Andrew Belmonte, associate professor of mathematics at Penn State and a member of the research team. Their study revealed experimentally, for the first time, the response of a viscoelastic material to increasingly extreme conditions of flow. "We found that flow happens at slow speeds, cutting happens at intermediate speeds, and tearing happens at the highest speeds," says Joseph R. Gladden, a co-author of the research paper, who collaborated on the study while he was a postdoctoral scholar at Penn State. The researchers also found that the viscoelastic material heals in the wake of the tear, as a torn solid would not, and recovers completely after several hours. "Surprisingly, the strength of the material when it acts like a solid is essentially the same as its surface tension as a liquid. This fact reconnects our understanding of these materials between the extremes of flow and fracture," said Belmonte.

Source: University of Minnesota