NASA Looks at Hurricane Cloud Tops for Windy Clues

Scientists at NASA are finding that with hurricanes, they can look at the cloud tops for clues about the behavior of winds below the hurricane on the Earth's surface.

By looking at how high up the rain is forming within clouds, scientists can estimate whether the hurricane's surface winds will strengthen or weaken. They have found that if rain is falling from clouds that extend up to 9 miles high, and that rain continues for at least one out of three hours, a hurricane's surface winds are likely going to get stronger.

To see into the cloud tops, NASA scientists developed a precise mathematical method or a technique with the very precise rain measurements from the radar onboard the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite. Once this technique was developed it was applied to data collected by National Weather Service radars on the ground.

"Thanks to the precise measurements from TRMM, we've found a new way to use data that's collected all the time by weather radars on the ground," said Owen Kelley, scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Kelley and scientists John Stout of NASA Goddard and Jeff Halverson of the University of Maryland Baltimore County calculated statistics that suggest forecasters could use TRMM's rain-height observations to improve existing observations and computer model forecasts of hurricane winds. "The trick is to keep an eye on the height of rain that radars see when a hurricane approaches within 200 miles of the coast," Kelley said.

The TRMM satellite and the ground radar work well together, especially during hurricanes because they each have an advantage. National Weather Service radars on the ground give less precise height measurements of rainfall than the TRMM satellite's radar, but ground radars can continuously observe a nearby hurricane for hours at a time, whereas TRMM's orbit prevents it from hovering over one spot.

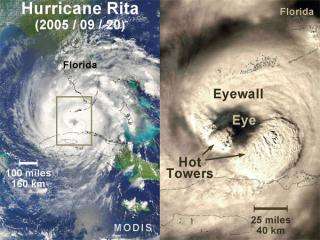

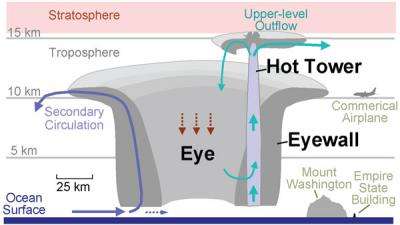

For several years, Kelley and his colleagues have been studying "hot towers," the towering high clouds in a hurricane's eyewall. The eyewall is the area of strong storms that surround a hurricane's mostly cloud-free eye. Hot towers can generate very heavy rainfall and reach the top of the troposphere, which extends 9 miles (14.5 km) above the Earth's surface in the tropics. These towers are called “hot” because a lot of heat is released inside them by water vapor condensing to form rain.

Hot towers are one window into the mystery of how hurricanes grow stronger. A single hot tower does not tell you much about a hurricane, but a rapid sequence of towers suggests that something unusual is going on deep inside the hurricane.

By combining measurements from many hurricanes, statistics show that if hot towers exist in the eyewall at least 33% of the time during a three-hour period, a hurricane's destructive surface winds have an 82% chance of intensifying. Otherwise, the chance of wind intensification drops to only 17%. The bottom line is that if several hot towers are present in a hurricane over a period of time, there's a higher probability of a storm intensifying.

Kelley is still searching for a more complete explanation of what causes these bursts of hot towers. Radar observations have shown conclusively that these bursts happen, but further research is needed to explain why and how.

TRMM, which was built by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and launched in 1997, has been orbiting the Earth watching rainfall from space.

This study appeared in an issue of Geophysical Research Letters in the fall of 2005. During the 2006 hurricane season, researchers both inside and outside NASA will continue to use TRMM to shed light on how hurricanes work.

Source: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, by Rob Gutro