The first Martian marathon

On Earth, the fastest runners can finish a marathon in hours. On Mars it takes about 11 years.

On Tuesday, March 24th 2015, NASA's Mars rover Opportunity completed its first Red Planet marathon— 26.219 miles – with a finish time of roughly 11 years and two months.

"This mission isn't about setting distance records; it's about making scientific discoveries," says Steve Squyres, Opportunity principal investigator at Cornell University. "Still, running a marathon on Mars feels pretty cool."

Runner-author Hal Higdon once said, "The marathon never ceases to be a race of joy, a race of wonder." That goes double for a marathon on another world where every mile promises a new discovery.

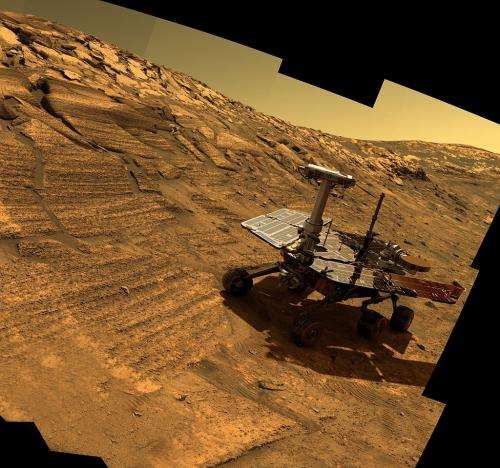

Opportunity's mission is to search for signs of ancient water. Today the Red Planet has a breathtakingly thin atmosphere, with conditions deadly to almost every known form of life on Earth. Billions of years ago, however, things might have been different. Many researchers believe that Mars was once warmer, wetter, and friendlier to potential Martian life. Opportunity's job is to search for clues to that ancient time.

Like many long-distance runners, Opportunity likes to "take it slow." On a typical drive day, the rover travels only 50 to 100 meters. This gives the rover time to safely traverse the rocky terrain, pause and look for the unknown. True to form, the long-lived rover surpassed the marathon mark during a drive of only 46.9 meters or 154 feet.

"When Opportunity landed on Mars 11 years ago, no one imagined this vehicle surviving a Martian winter, let alone completing a marathon," said Mars Exploration Rover Project Manager John Callas of JPL. To celebrate, the Mars rover team at JPL held a marathon-length relay race.

For Opportunity, just getting to the starting line was epic: "This particular marathoner had to fly about 283 million miles across space before being unceremoniously drop-bounced on the Martian surface in 2004," recalls Ray Arvidson, a member of the Opportunity science team from Washington University.

Opportunity first uncovered signs of water in deposits near the landing site in Eagle Crater. There were rocks that seemed to have formed in an ancient shallow lake, albeit too acidic for life. Next, mission planners set their sights on Endeavour Crater – an enormous pit 14 miles wide and hundreds of meters deep. Endeavour's depth would offer a look farther back into the history of Mars, to a time when the water was possibly less acidic.

The marathon route crossing Mars' Meridiani plain to Endeavour was a daring trek —with no aid stations anywhere. Raging dust storms reduced the rover's solar power so much that Opportunity almost entered the "sleep of death"; soft, sandy, wind-blown ripples trapped the rover's wheels, and there was an injury: a failure in Opportunity's right front steering actuator, which made running forward tricky. Ever resourceful, the rover ran part of its race backwards.

When the marathoner reached Endeavour Crater in August 2011, things got interesting.

"Endeavour is surrounded by fractured sedimentary rock, and the cracks are filled with gypsum," says Arvidson. "Gypsum forms when groundwater comes up and fills cracks in the ground, so this was good evidence for liquid water."

Moreover, the gypsum veins were likely formed in conditions less acidic and possibly more hospitable to life: Jackpot!

What's next? Opportunity is still going strong as it heads for a gap in the rim of Endeavour Crater where the rover will explore clay deposits for more signs of ancient water. The gap is called—you guessed it—"Marathon Valley."

Martian ultra-marathon, anyone?

Provided by NASA