Woman hoping for a chance to explore Mars, but skeptics question mission

Laura Smith-Velazquez is a dreamer - and she has been dreaming of going to space since the first time she looked into a telescope as an 8-year-old, later imagining herself commanding a starship while watching "Star Trek."

Every year she tries for a shot at NASA's astronaut program, with no luck.

But now, the 38-year-old engineer's chances of getting to space may have improved - the Owings Mills resident is one of 100 semi-finalists named last month by Dutch organization Mars One for a mission to establish a permanent colony on Mars by 2025. She said she is prepared to leave behind her husband of three years, who also applied for the one-way mission but didn't make the first cut.

The mission, devised by an entrepreneur and a space scientist from the Netherlands, has garnered worldwide attention, especially with its plans to help fund it by making it a reality TV spectacle.

Still, the odds are long, Smith-Velazquez and others acknowledge. Many view the Mars One mission as a publicity stunt. Organizations including NASA and the Planetary Society won't even comment on it, while scientists like Neil DeGrasse Tyson have questioned its aggressive timeline. An independent feasibility study last year suggested hazards including the possibility that crops grown inside the colony would produce suffocating levels of oxygen.

"To get to Mars you need rockets. You need spaceships," said John M. Logsdon, a professor emeritus at George Washington University who studies space policy. "None of that exists."

But Smith-Velazquez doesn't mind the skepticism. Just as the "space race" of the 1950s and 1960s seemed to stretch science, if humans don't strive to reach Mars, it won't happen, she said. And the scrutiny can only improve preparations for dealing with the planet's inhospitable environment, she added.

"Yeah, there's a lot of risk, but there's a lot of risk no matter what you do," she said. "I'm willing to take that risk."

Mars One acknowledges the risk, too, calling the mission a "phenomenal undertaking" that requires constant efforts to prevent delays and failures. The plan, developed in 2011, calls for sending rovers and cargo to Mars ahead of four-person crews.

Under the project's timeline, a demonstration mission is set for 2018 to prove that technologies needed for a human mission can work. A rover mission would follow in 2020 to select the best location for settlement and to prepare the surface for the arrival of cargo missions, set to begin in 2022.

The rover would set up the six cargo units and get the outpost up and running in time for the arrival of the first crew, set to launch some time in 2024 and land seven months later, likely in 2025.

Smith-Velazquez said she is used to confined spaces and zooming through the air - she has a pilot's license and studied at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida, and now works for defense contractor Rockwell Collins designing the interfaces pilots use to control aircraft. But she acknowledged the Mars One mission is daunting, starting with a seven-month journey with a crew of three other people before even making it to the settlement.

"It's not going to be easy, even if you're not claustrophobic," she said.

Smith-Velazquez said she isn't sure why she advanced so far in the selection process. Mars One has given little feedback in a process that required a lengthy written application, a video application, study of 40 pages of technical information about Mars, and a video chat interview.

The organization says it is looking for astronauts who are resilient, adaptable, curious, trusting, creative and resourceful, as well as at least 18 years old and physically capable.

After miscalculating the time difference with the Netherlands, she mistakenly scheduled her 10-minute interview for 1:20 a.m. on a Monday, but she was ready nonetheless and eager to speak with Dr. Norbert Kraft, Mars One's chief medical officer - whom she called "a legend in astronaut selection" for NASA.

She was asked whether she would come back from Mars, if that were possible, and why - something she figured might be intended to weed out those lacking commitment. Her answer was an unequivocal no, she said, "because the people you go with become your family."

Smith-Velazquez speculated it's her ability to get along with others that may have helped her stand out. Her Cherokee heritage, which was central to her upbringing in rural Michigan, also could be an asset in winning a spot among a diverse group, she said.

The project aims to be a global endeavor, with the pool of semi-finalists hailing from all over the world.

"It almost seems random in a way," she said.

Smith-Velazquez and her husband, Matthew Velazquez, applied together in August 2013, saying at first that either both would go or neither. But when Velazquez was left out of the first cut, from 200,000 applicants to 1,000, that "fell by the wayside in a big hurry," he said.

"As a husband, what do you do? Do you demand that you continue to have a wife on this planet, or do you let your wife do something she's always wanted to do?" said the 43-year-old aerospace engineer. "You have to be supportive of that."

Smith-Velazquez said her family also has been supportive.

But many in the aerospace industry remain skeptical. Tyson, the scientist known for presenting space to TV viewers on shows like "NOVA ScienceNow" and "Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey," told Business Insider he wouldn't sign up for the mission, which has struggled to find investors, though he said he supported its ambition.

Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who has served aboard the International Space Station, told an Australian journalist for an article posted on Medium.com that he feared the mission would end up being "a little disillusioning for people, because it's presented as if for sure it's going to happen."

Logsdon, the space policy professor, agreed that the attention could have negative consequences, though he said it at least shows a desire for human exploration still exists.

"I think people are fascinated with the idea of human travel to Mars," he said. "But I think their likely failure to do what they say they're going to do will give the whole idea of humans going to Mars a bad name."

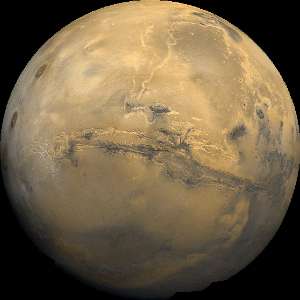

The planet presents would-be explorers with difficult engineering challenges. Mars' atmosphere is one-hundredth the density of Earth's, preventing oceans from being able to form on its surface and radiating heat away so effectively that temperatures drop from a comfortable 50-70 degrees in the sunshine to 100 degrees below zero at night.

"Any idea of going to Mars is ambitious," said Frank Summers, an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. "How do you pack in enough supplies and figure out how to generate your own supplies - air, heat and oxygen - when you get there? That's the major problem to solve."

A study by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that Mars One at least needs to reconsider some elements of its plans to keep settlers alive. While Mars One plans to use existing technology to accomplish the mission, the report found some new technology is needed. For example, a plan to pull water out of the Mars soil might not work, the report found.

The report also estimated that a plan to draw oxygen from crops inside the habitat and pump nitrogen from tanks into the air would leave the first settlers unable to breathe within 68 days.

Such plans are also, of course, costly. Mars One estimates it will cost $6 billion to get its first crew to Mars, though the MIT report suggested it likely will be higher. MIT scientists estimated that the rockets needed to get the supplies and astronauts to the planet would cost $4.5 billion alone.

Mars One plans to raise money through sponsorships, partnerships, sales of broadcast rights, investment from wealthy individuals, revenue from intellectual property and crowdfunding. A campaign on crowdfunding website last year raised $313,744 of a $400,000 goal for its lander mission scheduled for 2018.

Still, to Smith-Velazquez and other supporters, the mission is worth attempting. It took more than a dozen missions to orbit Mars - most of them failures - before the first spacecraft landed there in 1971, according to NASA. Since then, there have been more than a dozen successful missions to the planet, though also more failures.

"As a planet, you don't want to stagnate," Smith-Velazquez said. "Even if you don't get there, you get that impetus to spur new technology."

©2015 The Baltimore Sun

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC