China tiger farms put big cats in the jaws of extinction

A fearsome tiger snarled as a doomed chicken flapped helplessly in its mouth—but campaigners say such "entertainment" in China is putting big cats further in the jaws of extinction.

"How ferocious, he doesn't let anyone come near him," said one visitor over the sound of crunching bones, as she recorded the grisly scene on her smartphone.

Buying chickens to feed the exhibits at the Siberian Tiger Park in northeast China's Harbin city costs 60 yuan ($10)—though the menu has plenty of other choices, even cows are available to serve up.

But wildlife protection campaigners allege such parks, along with the dedicated tiger breeding centres or "farms" dotted around the country, actually make their big money selling on body parts from the big cats when they die—a practise which potentially further threatens the endangered species.

Global tiger numbers have plummeted from 100,000 a century ago to only 3,000 in the wild today, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, which classes them as endangered, with poaching and habitat loss primary threats to their survival.

China's tiger farm industry says the trade in captive animals helps to relieve the pressure on wild felines, but wildlife groups argue it reduces the stigma around buying the animals or their body parts, and could create new markets for them.

Debbie Banks, head of the London-based NGO the Environmental Investigation Agency, said that such sales of the body parts of captive tigers was "stimulating demand and sustaining the poaching pressure".

"Raising a tiger to maturity in captivity costs more than poaching a tiger in the wild," she told AFP.

"Wild tigers, leopards and snow leopards are targeted as a cheaper alternative to skins of captive bred tigers."

Figures from TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network, show that from the turn of the millennium, at least 1,590 tigers were poached around the world up to April 2014—an average of two a week.

Among the 13 countries with native tiger populations, numbers are increasing in India and Nepal, which do not have tiger farms, said Banks. But in Laos, Vietnam, Thailand and China, where tigers can legally be bred for commercial purposes, wild populations are struggling.

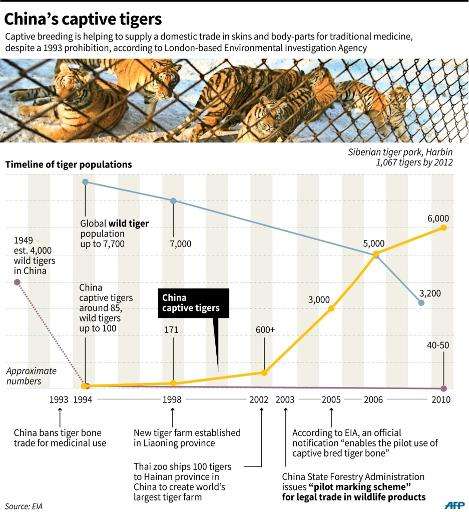

At the same time captive tiger numbers are soaring in China, with up to 6,000—twice the global wild population—in about 200 farms across the country.

Wanted dead or alive

Used for entertainment when the tigers are alive, what happens to the skins and bones of animals that die in captivity is a murky issue.

Tiger bones have long been an ingredient of traditional Chinese medicine, supposedly for a capacity to strengthen the human body.

China banned trade in tiger bones in 1993, but the law is regularly flouted, campaigners say. Legislation is also unclear on whether cats bred in captivity are considered endangered in China, and there is little regulation around what needs to be declared when they die.

The animal is considered a symbol of prestige for many in China, with tiger pelt rugs sought-after luxury items, along with tiger bone wine—bottles labelled with tiger images sell for nearly 5,000 yuan ($800) at the park shop in Harbin.

In December, a wealthy Chinese businessman who bought, slaughtered and ate three tigers was jailed for 13 years.

The gang involved had killed 10 tigers in total, domestic media reported, some of them smuggled in alive "from Southeast Asian countries".

The tigers cost them 200,000 to 300,000 yuan ($48,000) each, and they reaped profits of more than 100,000 yuan per animal, reports said.

Chinese tiger purchases came under scrutiny at an anti-poaching conference in Nepal last week attended by around 100 experts, government and law officials from tiger habitat nations.

Campaigners say that the mere availability of "farmed" tiger products fuels the demand, which Mike Baltzer, leader of the WWF Tigers Alive Initiative, described as "so huge that it's very difficult to address the issue".

"When you have a cultural perception among wealthy people in China that owning a tiger is a matter of prestige, you can't change it overnight," he said.

Foreign ministry spokesman Hong Lei insisted that Beijing was taking action to tighten laws against poaching, adding: "We have adopted a recovery plan on China's wild tigers and work to improve the habitats of wild tigers."

Big cat in a bottle?

There are only about 45 wild tigers in China, according to EIA. But there are more than 1,000 at the Siberian Tiger Park, which was launched in 1986 with just eight animals.

Park representatives have repeatedly been quoted saying that the trade in captive-bred tiger products reduces pressure on wild animals, and that they hope to reintroduce some of their creatures into the wild.

But repeated requests by AFP for comment on whether they sell on the dead animal parts or use them in products went unanswered.

In the park's souvenir shop "bone strengthening wine" is sold in elaborate bottles adorned with tigers.

A shop assistant denied to a foreign visitor that tiger bone was an ingredient.

But when AFP telephoned the shop an employee gave a different impression, saying: "In order to avoid the penalties for selling tiger-bone wine, the name was changed from 'tiger bone wine' to 'bone strengthening wine.'"

© 2015 AFP