BoarCroc, RatCroc, DogCroc, DuckCroc and PancakeCroc

A suite of five ancient crocs, including one with teeth like boar tusks and another with a snout like a duck's bill, have been discovered in the Sahara by National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Paul Sereno. The five fossil crocs, three of them newly named species, are remains of a bizarre world of crocs that inhabited the southern land mass known as Gondwana some 100 million years ago.

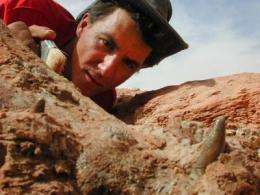

Sereno, a professor at the University of Chicago, and his team unearthed the strange crocs in a series of expeditions beginning in 2000 in the Sahara. Many of the fossils were found lying on the surface of a remote, windswept stretch of rock and dunes. The crocs galloped and swam across present-day Niger and Morocco when broad rivers coursed over lush plains and dinosaurs ruled.

"These species open a window on a croc world completely foreign to what was living on northern continents," Sereno said. The five crocs, along with a closely related sixth species, will be detailed in a paper published in the journal ZooKeys and appear in the November 2009 issue of National Geographic magazine. The crocs also will star in a documentary, "When Crocs Ate Dinosaurs," to premiere at 9 p.m. ET/PT Saturday, Nov. 21, on the National Geographic Channel.

At 40 feet in length and weighing 8 tons, Sarcosuchus imperator, popularly known as SuperCroc, was the first and largest of the crocs Sereno found in the Sahara, but it was not the strangest, Sereno said. He and his teams soon discovered key fossils of five previously unknown or poorly understood species, most of them walking "upright" with their arms and legs under the body like a land mammal instead of sprawled out to the sides, bellies touching the ground.

The crocs and their nicknames:

- BoarCroc: New species, Kaprosuchus saharicus; fossils found in Niger. Twenty-foot-long upright meat eater with an armored snout for ramming and three sets of dagger-shaped fangs for slicing. Closest relative found in Madagascar.

- RatCroc: New species, Araripesuchus rattoides; fossils found in Morocco. Three-foot-long, upright plant and grub eater. Pair of buckteeth in lower jaw used to dig for food. Closest relative in South America.

- PancakeCroc: New species, Laganosuchus thaumastos; fossils found in Niger and Morocco. Twenty-foot-long, squat fish eater with a three-foot pancake-flat head. Spike-shaped teeth on slender jaws. Likely rested motionless for hours, its jaws open and waiting for prey. Closest relative from Egypt. The scientific paper also names a close relative discovered by the team in Morocco, Laganosuchus maghrebensis.

- DuckCroc: New fossils of previously named species, Anatosuchus minor. Fossils found in Niger. Three-foot-long upright fish-, frog- and grub-eater. Broad, overhanging snout and Pinocchio-like nose. Special sensory areas on the snout end allowed it to root around on the shore and in shallow water for prey. Closest relative in Madagascar.

- DogCroc: New fossils of named species, Araripesuchus wegeneri. Fossils found in Niger include five skeletons, all next to each other on a single block of rock. Three-foot-long upright plant and grub eater with a soft, doglike nose pointing forward. Likely an agile galloper, but also a capable swimmer. Closest relative in Argentina.

"We were surprised to find so many species from the same time in the same place," said paleontologist Hans Larsson, associate professor at McGill University in Montreal and a team member who discovered the bones of BoarCroc and PancakeCroc. "Each of the crocs apparently had different diets, different behaviors. It appears they had divided up the ecosystem, each species taking advantage of it in its own way."

To better understand how these ancient crocs — mostly upright and agile — might have moved and lived, Sereno traveled to northern Australia, where he observed and captured freshwater crocs. Realizing while there that he may have stumbled onto one of the keys to crocodilian success, Sereno saw freshwater crocs galloping at full speed on land and then, at water's edge, diving in and swimming away like fish. On land they moved much like running mammals, yet in a flash turned fishlike, their bodies and tails moving side to side, propelling them in water.

Based on interpretation of the fossils, Sereno and Larsson hypothesize that these early crocs were small, upright gallopers. In the scientific paper, they suggest that the more agile of their new croc menagerie could not only gallop on land but also evolved a swimming tail for agility and speed in water, two modes of locomotion suggested to be evolutionary hallmarks for the past 200 million years.

"My African crocs appeared to have had both upright, agile legs for bounding overland and a versatile tail for paddling in water," Sereno writes in the National Geographic magazine article. "Their amphibious talents in the past may be the key to understanding how they flourished in, and ultimately survived, the dinosaur era."

To study the crocs' brains, Sereno CT-scanned the skulls of DuckCroc and DogCroc and then created digital and physical casts of the brains. The result: Both DogCroc and DuckCroc had broad, spade-shaped forebrains that look different from those of living crocs. "They may have had slightly more sophisticated brain function than living crocs," Larsson said, "because active hunting on land usually requires more brain power than merely waiting for prey to show up."

To collect the croc fossils, Sereno and his teams endured temperatures topping 125 degrees F, living for months on dehydrated food. Logistics were challenging: For the 2000 expedition, they transported trucks, tools, tents, five tons of plaster, 600 pounds of water and four months' worth of other supplies.

More information: The scientific paper can be access at: pensoftonline.net/zookeys/index.php/journal/index

Source: National Geographic Society (news : web)