Scientists rotate electron spin with electric field

Researchers at the Delft University of Technology’s Kavli Institute of Nanoscience and the Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter (FOM) have succeeded in controlling the spin of a single electron merely by using electric fields. This clears the way for a much simpler realization of the building blocks of a (future) super-fast quantum computer.

The scientists will publish their work in Science Express on Thursday 1 November.

Controlling the spin of a single electron is essential if this spin is to be used as the building block of a future quantum computer. An electron not only has a charge but, because of its spin, also behaves as a tiny magnet.

In a magnetic field, the spin can point in the same direction as the field or in the opposite direction, but the laws of quantum mechanics also allow the spin to exist in both states simultaneously. As a result, the spin of an electron is a very promising building block for the yet-to-be-developed quantum computer; a computer that, for certain applications, is far more powerful than a conventional computer.

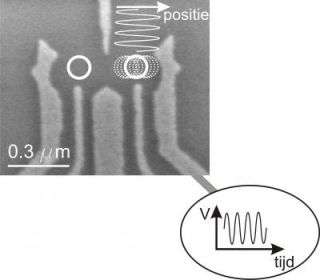

At first glance it is surprising that the spin can be rotated by an electric field. However, we know from the Theory of Relativity that a moving electron can ‘feel’ an electric field as though it were a magnetic field. Researchers Katja Nowack and Dr. Frank Koppens therefore forced an electron to move through a rapidly-changing electric field. Working in collaboration with Prof. Yuli V. Nazarov, theoretical researcher at the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience Delft, they showed that it was indeed possible to turn the spin of the electron by doing so.

The advantage of controlling spin with electric fields rather than magnetic fields is that the former are easy to generate. It will also be easier to control various spins independently from one another - a requirement for building a quantum computer - using electric fields. The team, led by Dr. Lieven Vandersypen, is now going to apply this technique to a number of electrons.

Source: Delft University of Technology