A swing and a near-miss: Comet siding-spring clears the fence over Mars' satellite-filled outfield

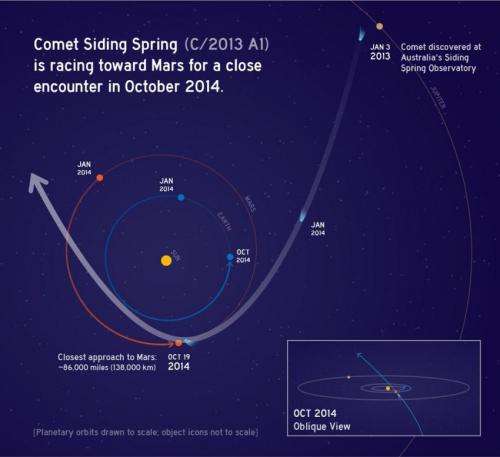

Like a runner rounding third base on his way to home plate, comet Siding Spring will sprint past Mars this October while making a beeline for the Sun. Siding Spring's buzz of the red planet will afford us not only an unprecedented peek at a fresh comet, but also front-row seats for a historical look back at the ancient Solar System.

"Comets like this one, which formed long ago and remained for billions of years in the icy regions beyond Pluto, still contain the primeval building materials of our solar system in their original state," said Dr. Dennis Bodewits, lead researcher on the UMD astronomy team that used NASA's Swift satellite to estimate the comet's size and activity.

Siding-Spring is a new comet coming from an old place: the Oort cloud. The Oort Cloud, named for the astronomer who predicted its existence, is a spherical shell of icy bodies that dwell between five thousand and 100 thousand AU from the Sun. One AU is equivalent to the distance between the Sun and the Earth.

"Comets formed early in the evolution of the solar system," Bodewits told Astrobiology Magazine, "while material was accreting to form planets. When proto-planets became large enough, a population of comets was dynamically ejected into the Oort cloud, where some remain stored until today."

The Oort cloud is one of two jumping-off points for comets into the inner solar system. Comets that visit frequently, like Halley's comet, have what are called short periods. Most come from the Kuiper Belt - a ring of objects just beyond the orbit of Neptune. Pluto, a dwarf planet, also originated from the Kuiper Belt. Siding Spring and other comets with long periods of more than 200 years between visits to the Sun come from the distant space beyond Pluto and from a distant time, and carry original Solar System material.

"Comets entering the inner solar system for the first time are called Dynamically New comets" said Bodewits. "These objects have never been heated by the Sun and retain some of the most primordial material available for observation in the solar system."

Standing by to greet Siding Spring on its first pass by the inner planets will be a small fleet of satellites. The welcoming committee consists of five total spacecraft, with some long-timers and a couple of new recruits.

From the classic team, there's the Mars Odyssey. In orbit since 2001, it currently assists ground-based rover communication with Earth. Up next is the Mars Express, which has been searching for water for the past decade. Then there is the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which also looks for water while studying global weather and making high-resolution maps.

The fresh faces on the scene will be MAVEN and MOM. The Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) satellite will arrive first. MAVEN's mission is to study the Martian upper atmosphere. It will be be perfectly positioned and ideally equipped to study Siding Spring's corona, the edge of which will sweep into Martian airspace as it passes by. Last, but definitely not least, arriving just in the nick of time will be ISRO's Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM). MOM a mass spectrometer capable of analyzing the comet's contents and a camera that could capture organic molecules like methane.

"This may very well be the only time we ever get to see the nucleus of a Dynamically New comet," said Bodewits. "The Mars mission teams are currently investigating how they safely study the comet and its impact on Mars' atmosphere."

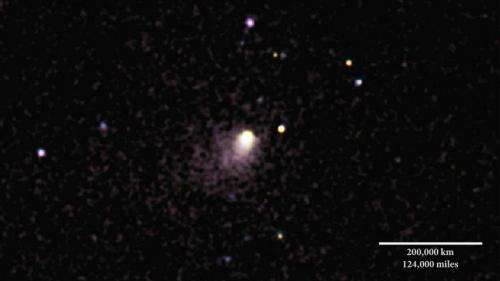

For the moment, the Swift satellite is keeping a close eye on Siding Spring.

Swift started observing Siding Spring in November 2013 when it was 4.5 AU from the Sun. It will continue observing until at least January 2015, when Sliding Spring heads out of the Solar System forever. Detailed observations by Swift have already revealed much about this new visitor from the far-away. For instance, Siding Spring's nucleus—which Swift measured to be a little smaller than 7 American football fields (700 meters/2,300 feet)—became active when the comet was 2.5 AU from the Sun. Since then, water has begun flying from the comet's surface at a rate of 49 liters (13 gallons) every second. At that rate, Comet Siding Spring could fill 12 Olympic-sized swimming pools per week.

Also observed was Siding-Spring's alarming trajectory.

At first, the comet appeared to possibly be heading right for the red planet - or at least within range of the team of satellites in orbit. Siding Spring will sidle up to Mars at a distance of just 83,000 miles (132,000 km). To put that into perspective, the closest documented comet approach to Earth was 1.4 million miles (2.3 million km). On July 1, 1770, comet Lexell came as close to Earth as any comet in recorded history, and it was still six times further out than the Moon.

On October 19th, 2014, comet Siding Spring will pass sixteen times closer to Mars than any comet has come to Earth, to date. That's so close that Siding Spring will graze the outer Martian atmosphere. Gas and dust from the comet's own coma will mingle with the ionosphere being actively studied by MAVEN. In the process, we may learn something very new—or something very old—at no extra charge courtesy of Siding Spring's serendipitous fly-by.

Rather than rain on the game in progress around Mars, Siding Spring will be a welcome guest in the ballpark.

"The comet's orbit is well determined and there is no risk of an impact on Mars," said Bodewits. "The Swift measurements showed that the comet is probably small and not very active. Dynamically new comets, however, are unpredictable. Swift will keep a close eye on the comet as it grows more active."

Provided by Astrobio.net

This story is republished courtesy of NASA's Astrobiology Magazine. Explore the Earth and beyond at www.astrobio.net . Original story here