This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

proofread

Five ways to keep towns cool in a heat wave

Along with warmer and wetter winters across the UK and Europe, our summers are getting hotter with more frequent periods of extreme hot weather. And as well as affecting agriculture, infrastructure and wildlife, hot weather influences us.

Particularly for younger and older people and those with existing conditions, heat can affect human health. It reduces our ability to concentrate and learn. Heat waves have been linked to increased aggressive behavior. Effects are both direct, in terms of lost productivity, and indirect in terms of longer-term economic effects.

I was recently involved in the cool towns project, working with researchers from Belgium, France and the Netherlands. Our aim was to show how cities could develop heat resilience strategies by using local interventions to increase thermal comfort in priority areas.

We began by developing a method, set out in our urban heat atlas to identify where heat stress was most likely to occur. Next, we mapped vulnerability to heat by identifying priority locations for those most at risk.

We found transport hubs, where people gather to wait for buses or trains, school playgrounds and market squares came into this category, along with walking and cycle routes from residential areas to facilities and workplaces.

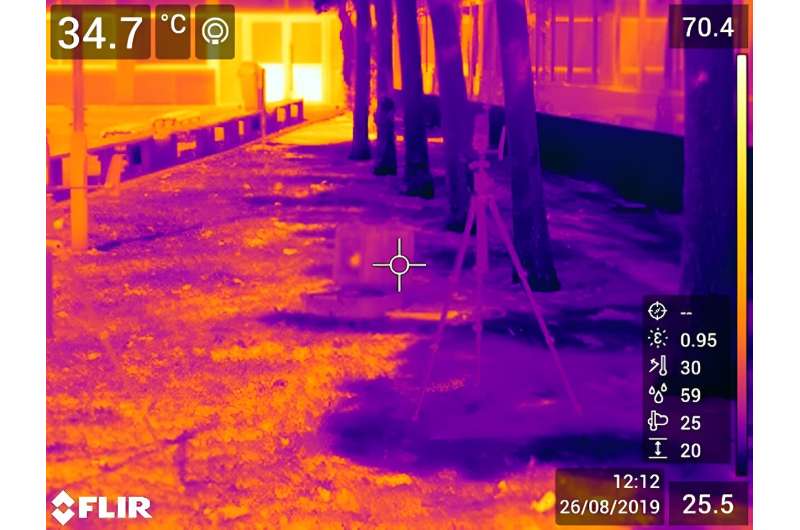

Thermal comfort refers to how individuals feel in different conditions and we used mobile weather stations to calculate physiological equivalent temperature. This is a measure that takes into account the humidity, incident radiation (the amount of solar energy that hits the ground), wind speed and air temperature.

Prior to our research there was hardly any information on the effectiveness of different interventions on physiological equivalent temperature and none at all from northern Europe. We carried out measurements and identified five of the most scalable solutions that reduce impacts of heat waves:

1. Shade

It will be no surprise that people are cooler in the shade than in full sun. Planting trees has many benefits, so it's likely to be the first choice for landscape architects and urban planners although shade intensity varies with species. It can be challenging to add trees on roadsides due to underground services such as pipes and cables. They require maintenance particularly as trees establish their root systems.

Trees, and other vegetation, including grass, were found to have a cooling effect that extended beyond the immediate area. Where planting trees is not possible, textile shade structures can be used. These can easily be removed in winter allowing the sun to penetrate.

2. Water features

Fountains and water playgrounds have a cooling effect when people can have direct contact with the water and when spray falls on the ground then cools by evaporation. However, like rivers, while the water itself is cooler than the surroundings the effect is localized although increased downwind.

3. Special paving

Permeable or vegetated paving consists of a matrix of interlocking recycled plastic grids or concrete paving. This provides a firm surface while also enabling grass or other low plants to grow in the gaps, and is cooler than asphalt or solid paving. This also allows water to infiltrate the soil which in turn reduces the risk of surface water flooding. Low-growing plants are used so as not to create issues for wheelchair or pushchair users.

4. Green walls

Green walls come in many forms and are effective at insulating buildings, reducing the need for internal temperature regulation. They look attractive and benefit biodiversity. Like green roofs, these reduce the urban heat island effect. However, the influence on thermal comfort is only felt nearby.

5. Better urban planning

Together, the total of all the parks, private gardens, green roofs, street trees and water bodies (collectively known as green-blue infrastructure) reduce the urban heat island effect of building materials absorbing and later releasing heat. This cools down cities, particularly at night.

Heat-resilient strategies are becoming more common as decision makers respond to the impacts of the changing climate and meeting net zero targets. Landscape architects and urban planners can be encouraged to incorporate small-scale interventions for thermal comfort which combined to mitigate the urban heat island effect.

Barriers to implementation in new development and upgrading schemes are not limited to initial outlay. Challenges include ongoing maintenance costs, cold weather comfort, public safety and acceptability as well as access for routine and emergency services which all need to be considered. The roadmap produced by the cool towns project provides practical advice, with examples, on developing city wide heat resilient strategies.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()