Deep insight into interfaces between materials

Interfaces between different materials and their properties are of key importance for modern technology. Together with an international team, physicists of Würzburg University have developed a new method that allows them to closely analyze these interfaces and to model their properties.

In his Nobel Lecture on December 8, 2000, Herbert Kroemer coined the phrase, "the interface is the device." Kroemer referred to the mature field of semiconductor heterostructures, which form the basis of all modern electronics.

However, with the advent of novel, powerful devices based on more complex and versatile topological and correlated materials, that statement is timelier than ever. Recently, physicists from Würzburg University and coworkers from Germany, Canada, the U.S.A. and Korea have developed a new method to uncover important charge properties of correlated oxide interfaces with unprecedented atomic scale resolution. The team of Professor Vladimir Hinkov and his coworkers report about this experimental method in the current issue of the Nature journal npj Quantum Materials.

"Conventional electronic chips are based on networks of so-called p-n junctions, interfaces between semiconductors carrying positive and negative charges, respectively," says Vladimir Hinkov, describing the background of this research. There are several drawbacks to such a setup: First, the junctions are thick, often on the order of hundreds of interatomic spacings. Second, operating the network requires the movement of many electrons, which costs a lot of energy due to electrical resistance. Third, semiconductors do not intrinsically have magnetic properties and their electron configuration is very basic. "This dramatically limits the ways to build functional junctions and to realize magnetic applications," Hinkov reports.

Versatile properties require sophisticated methods

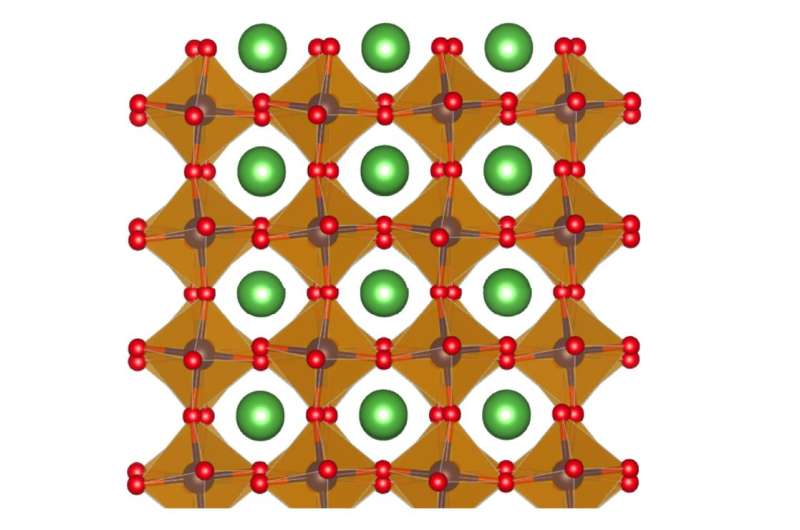

Transition-metal oxides, on the other hand, exhibit many different properties. Some of them are ferromagnetic, others are antiferromagnetic, and others in turn are high-temperature superconductors with very unconventional properties. Forming interfaces between such materials yields many phenomena that hold promise for novel applications such as different sensors, lossless computer memory and ultrafast processors. The price is that more sophisticated tools are necessary to study them. This is due to the variety of phenomena and due to the much shorter length scale over which the properties of oxides change at such heterointerfaces, which is often just a few atomic spacings.

Of crucial importance is the behavior of electrons at the interface: Do they tend to accumulate? Which orbitals do they occupy, i.e. how do the electron clouds arrange around the atoms? Is there magnetic order, i.e. do the tiny magnetic moments of the electrons called spins align relative to each other, establishing magnetic order? Physicists around the world are seeking answers to these questions.

Measurements on an atomic scale

Hinkov and coworkers developed new method and analysis software that provides answers. It is based on "resonant x-ray reflectometry," a technique exploiting X-ray light created at a synchrotron with atomic-scale resolution of less than one nanometer. The physicists apply the technique on thin films of lanthanum cobalt oxide, a material that has interesting magnetic properties.

In their present work, however, the scientists have concentrated on another aspect: "Before we can delve in the rich magnetic phenomena of this material, we first have to solve a fundamental, widespread problem," says Professor Hinkov. "Like many other materials, such as simple table salt and many semiconductors, lanthanum cobalt oxide consists of charged particles. These so-called ions form a sequence of positively and negatively charged atomic layers, stacked on a 15-nanometer-thin film. One can show that enormous electrostatic fields form between the layers, which is a problem, since they cost a lot of energy," Vladimir Hinkov says.

"Nature is economical and avoids these field energy costs. It brings positive and negative charges to the opposite faces of the film, respectively, just like between the plates of a capacitor. A new field is formed, which is opposite to the original one and which cancels it."

Corrugated interfaces constitute a problem

This accumulation of pure electronic charge at the film faces is called "electronic reconstruction." According to the physicists, this is a very elegant solution, since it preserves the film face smoothness. For materials in which electronic reconstruction is not possible, the compensating charge is provided by comparatively large ions, which results in corrugated film faces. As Hinkov explains, such corrugations are detrimental for devices based on film interfaces, especially when, like in transition-metal oxides, the material properties change on an atomic scale at the interface.

Exploiting the new method, the present work shows microscopic evidence that electronic reconstruction is realized at transition-metal oxide interfaces. The method also could enable the study of microscopic properties of such interfaces, which are not limited to electronic reconstruction, but encompass the arrangement of chemical elements, the electronic occupation of atomic orbitals and the spin orientation.

More information: Jorge E Hamann-Borrero et al. Valence-state reflectometry of complex oxide heterointerfaces, npj Quantum Materials (2016). DOI: 10.1038/npjquantmats.2016.13

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg