The outrage factor in gender and science

There's a lot of outrage about outrage storming around women in science and science journalism at the moment. And fear of causing it, too.

It's easy to cast outrage as inimical to thinking and discussion. It's not unusual to want to curtail debate once it has been aroused.

That's probably a vain hope – and perhaps a lost opportunity as well. When outrage is spreading unusually widely, it signals a need for more thought and discussion, not less.

"The outrage factor" is a theory in risk communication. It led some scholars to grapple with measurement, although it's a narrow field. Still, I found this area of outrage management an interesting entry point to thinking about the outbreak of intense passionate debate that begun with a lunch in Korea a month ago.

The theory was developed by Peter Sandman. You can't manage communication about environmental risks effectively, he argued, if you don't consider the level of potential to invoke an extreme emotional response.

A risk, in this view, is never just a hazard: Risk = Hazard + Outrage. The outrage factor may be anywhere from negligible to catastrophically high. Any situation with a high potential outrage factor is high risk, even if only a small direct hazard to people is involved.

Sandman lists 20 components that contribute to the potential for outrage. Even though Tim Hunt's comments weren't about an environmental risk, we can still check off a good bunch of items on this list – like fairness, moral relevance, identifiable victims, amount of trust for experts or authorities, vulnerable populations, attractiveness to media, and the possibility of collective action.

You didn't need any academic theory, though, to know that wading into gender generalizations – even flippantly – was foolhardy territory for a formal guest at an event intending to honor women in science at a journalists' conference. Progressing women's rights to equal dignity and opportunity has always elicited outrage. But for the last couple of decades, sexist remarks and sexist jokes have, too.

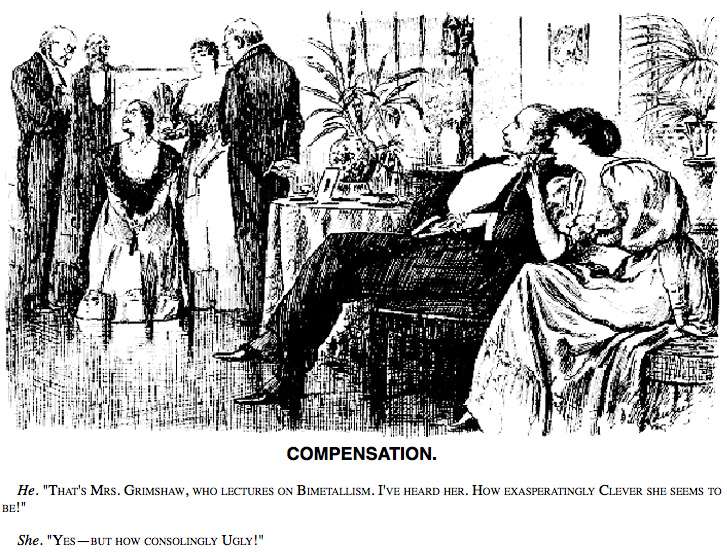

This cartoon by Punch contributor George du Maurier comes from 1895. That was the era when anthropological claims about lower female intelligence had been losing ground as a way to keep women out of higher education (Joan Burstyn, 1973). So the ground had shifted to fanning medical fears to discourage women from higher study – nervous problems, threats to ovaries, and the like.

Du Maurier uses "ugliness" as the stereotype basis for his joke about an intellectual woman. That one was also part of the standard repertoire for demeaning suffragettes. And it's still going strong in 2015.

Another commonality across time has been many thinking that women who want more respect are over-reacting: maybe they had a point with this or that, but this time, they've gone too far.

Whether or not events arouse outrage in each of us has partly do with how seriously we view a problem, and whether we can feel a close identification with any of those involved. Our ability to identify with victims can also often face a strong pull towards explanations that reassure us that our own corner of the status quo doesn't need to be disturbed.

Those factors split sympathies in a variety of combinations as the Tim Hunt controversy gained force. It sent us quickly into different corners – or left us torn between them. Was what he said a big deal or was it harmless? Did people identify more with being vulnerable to sexism or to putting their foot in their mouth?

The distress and harm to a small number of individuals at the eye of the storm was immediate and obvious. For many, though, the distress Hunt's comments caused others, along with the large-scale outbreak of sexist (and worse) opinion that inevitably followed, didn't count. A high-status representative of science's upper echelons declaring his own sexism and offering arguments to justify it on national radio is likely to encourage sexism and discriminatory behavior. But the specific women harmed that way aren't right there in front of our eyes.

I think this image of a bathing beach policeman enforcing a "no higher than six inches above the knee" order captures another of the reasons that keeps the Tim Hunt controversy steaming ahead.

Most of us have some kind of "protected values". They are ones that have a moral force for us. We don't like to trade them off against anything. A protected value in the mix is a common source of rigidity and anger that ramps up to outrage.

Egalitarianism is a protected value for many people. But the desire not to police people over those values is itself a protected value – and often for the same people.

In a collection of essays on "political correctness", its editor, Sarah Dunant, writes: "What PC has done is achieve the remarkable double whammy of offending both the right and a good deal of the left at the same time".

In one of the essays in Dunant's book, Stuart Hall writes that the concern over "PC" is a backlash to the fast social change of the 1960s – a resistance to the intrusion of the political into the personal. Two reasons for opposing it are that on the one hand, it's regarded as dealing with a trivial symptom not a cause – I'll come back to that. And on the other, it's seen to represent a form of policing. That is a hot button issue at academic institutions in particular.

When a rights-based complaint is seen as trivial by a group that's strongly "anti-PC", outrage from competing protected values can be propelled into high-speed collision. When feminism is involved, that can quickly draw a crowd that gets very ugly, and it certainly did here. Once it tapped into the rich vein of resentment many have about journalists too, it brought "Gamergate" energy and its signature torrent of extreme online abuse into the arena.

The backlash outrage fueled conspiracy theorizing and a repetitive re-telling of events into a new narrative where Tim Hunt was purely an innocent victim beset by villains. I had published a blog post on the centrality in the debate of dismissing Hunt's remarks because they were "just a joke" – a couple of days before it was claimed as news that it had been a joke. It's a tribute to the power of revision that so many now argue that its status as a joke had been withheld from the public debate.

In this revision, the original outrage had not been about his remarks and radio statements at all – it had all been based on a false portrayal of the man's character. Watching that version of events become a dominant narrative for many, and seeing all the concerns expressed before 24 June thereby discounted as based on a debate about something else, was particularly fascinating.

As people got to know Tim Hunt the person – most had never heard of him before or knew little of him – identifying with his distress rather than the harm his statements were causing became easier. "We didn't realize it had just been a joke" seemed to become an easier way to explain any shift in sentiment though. On the other hand, those who argue it was "just" about Hunt's reputation are underestimating how utterly devastating the experience must be for him and those close to him.

Which brings me to the outrage about outrage itself.

Many think of all outrage as purely negative in its consequences, and as invariably punitive. I think that's a misconception – and it is part of why the over-the-top violence-based rhetoric of pitchfork-wielding mobs is so rampant.

In the 2015 edition of his book, Networks of Outrage and Hope, Manuel Castells writes that the anger of outrage plays a critical role for people whose desire for dignity in daily life is not respected. It creates togetherness with others in the same position, and helps them overcome the fear of speaking out. (If you don't have access to the book, there's an interview with him about it here.)

The internet, writes Castells, enabled a new form of genuine democracy to emerge as more people can voice their opinions than the mechanisms of traditional media and public institutions allowed. Online communication enabled what he calls mass self-communication,

…based on horizontal networks of interactive communication that by and large, are difficult to control by governments or corporations… Mass self-communication provides the technological platform for the construction of the autonomy of the social actor, be it individual or collective, vis-a-vis the institutions of society… Thus, communication networks are decisive sources of power-making…

Concretely speaking: if many individuals feel humiliated, exploited, ignored or misrepresented, they are ready to transform their anger into action, as soon as they overcome their fear. And they overcome their fear by the extreme expression of anger, in the form of outrage, when learning of an unbearable event suffered by someone with whom they identify. This identification is better achieved by sharing feelings in some form of togetherness created in the process of communication…

In our time, multimodal, digital networks of horizontal communication are the fastest and most autonomous, interactive, reprogrammable and self-expanding means of communication in history… This is why the networked social movements of the digital age represent a new species of social movement.

The Tim Hunt furor vividly highlights the extent to which concerns about everyday sexism are regarded as trivial – a minor nuisance that's a kind of social hazard of being a woman, something to just shrug off and go about our science. As though that's unconnected from anything serious. Yet, as Virginia Valian writes, the mountains of disadvantage women face are made of molehills "piled one on top of the other".

Everyday, or mild, sexism (including jokes) imposes a burden of disrespect and workplace incivility. That doesn't mean it happens to everyone, or that it bothers everyone. But workplace incivility is common, and it's part of sustaining a climate that allows discrimination against individuals to thrive. That climate includes under-recognized and under-reported workplace harassment. And a society where there's been no substantial drop since the 1990s, but perhaps an increase, in sexual assault against young women.

Uta Frith, chair of The Royal Society's Diversity Committee, wrote, the swift, wide, and strong reaction to Tim Hunt's comments "was an outpouring waiting to happen". How do you mitigate against individuals being harmed when that happens though?

We're still finding our way through this. The analogy of storm seems to me far more useful than ones based on violence: we can shut the metaphorical doors against digital communication, not fuel it, and wait for it to pass. Apology, showing care for those other than yourself who were harmed by your actions, and not seeking personal redemption during the storm seem to be the best outrage minimization/reduction strategies for an individual.

For the rest of us, understanding and impulse control are essential to finding a path that doesn't encourage cruelty. But can deep, meaningful, societal change be achieved at more than a glacial pace only through non-confrontation? Historically, it hasn't. Action can't really be avoided if the intractable harm caused by hostility and lack of empathy to the distress of women and minorities is to really shift. The outrage isn't just negative: it's a sign of hope and enthusiasm for creating a better future, too.

Times have changed in some ways, but Eleanor Roosevelt's words in her speech on the 10th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1958 resonate still:

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerned citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.

Provided by Public Library of Science

This story is republished courtesy of PLOS Blogs: blogs.plos.org.