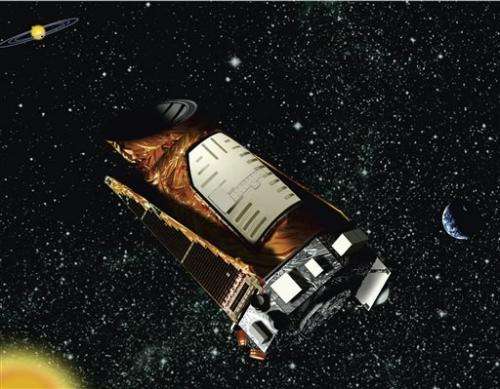

Kepler spacecraft's planet-hunting days may be numbered (Update)

NASA's planet-hunting Kepler telescope is broken, potentially jeopardizing the search for other worlds where life could exist outside our solar system.

If engineers can't find a fix, the failure could mean an end to the $600 million mission's search, although the space agency wasn't ready to call it quits Wednesday. The telescope has discovered scores of planets but only two so far are the best candidates for habitable planets.

"I wouldn't call Kepler down-and-out just yet," said NASA sciences chief John Grunsfeld.

NASA said the spacecraft lost the second of four wheels that control its orientation in space. With only two working wheels left, it can't point at stars with the same precision.

In orbit around the sun, 40 million miles (65 million kilometers) from Earth, Kepler is too far away to send astronauts on a repair mission like the way Grunsfeld and others fixed a mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope. Over the next several weeks, engineers on the ground will try to restart Kepler's faulty wheel or find a workaround. The telescope could be used for other purposes even if it can no longer track down planets.

Kepler was launched in 2009 in search of Earth-like planets. So far, it has confirmed 132 planets and spotted more than 2,700 potential ones. Its mission was supposed to be over by now, but last year, NASA agreed to keep Kepler running through 2016 at a cost of about $20 million a year.

Just last month, Kepler scientists announced the discovery of a distant duo that seems like ideal places for some sort of life to flourish. The other planets found by Kepler haven't fit all the criteria that would make them right for life of any kind—from microbes to man.

While ground telescopes can hunt for planets outside our solar system, Kepler is much more advanced and is the first space mission dedicated to that goal.

For the past four years, Kepler has focused its telescope on a faraway patch of the Milky Way hosting more than 150,000 stars, recording slight dips in brightness—a sign of a planet passing in front of the star.

Now "we can't point where we need to point. We can't gather data," deputy project manager Charles Sobeck told The Associated Press.

Scientists said there's a backlog of data that they still need to analyze even if Kepler stopped looking for planets.

"I think the most interesting, exciting discoveries are coming in the next two years. The mission is not over," said chief scientist William Borucki at the NASA Ames Research Center in Northern California, which manages the mission.

Scientists who have no role in the Kepler mission mourned the news. They said the latest loss means the spacecraft may not be able to determine how many Earth-size planets are in the "Goldilocks zone" where it's not too hot or too cold for water to exist in liquid form on the surface. And while they praised the data collected by Kepler so far, they said several more years of observations are needed to nail down that number.

"This is one of the saddest days in my life. A crippled Kepler may be able to do other things, but it cannot do the one thing it was designed to do," Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who is not part of the Kepler team, said in an email.

In 2017, NASA plans to launch TESS—Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite—designed to search for planets around nearby stars.

More information: Kepler: kepler.nasa.gov

© 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.