Astronomy without a telescope -- why carbon?

Last week's AWAT Why Water? took the approach of acknowledging that while numerous solvents are available to support alien biochemistries, water is very likely to be the most common biological solvent out there – just on the basis of its sheer abundance. It also has useful chemical features that would be advantageous to alien biochemistries – particularly where its liquid phase occurs in a warmer temperature zone than any other solvent.

We can constrain the number of possible solutes likely to engage in biochemical activity by assuming that life (particularly complex and potentially intelligent life) will need structural components that are chemically stable in solution and can sustain their structural integrity in the face of minor environmental variations, such as changes in temperature, pressure and acidity.

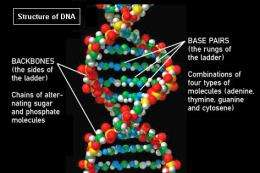

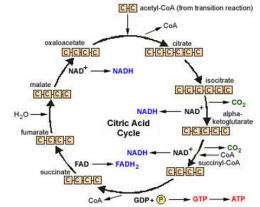

Although DNA is often discussed as a core component of life on Earth, it is conceivable that a self-replicating biochemistry came later. The molecular machinery that supports the breakdown of carbohydrates uses relatively uncomplicated carboxylic acids and phospholipid membranes – although the whole process today is facilitated by complex proteins, which are unlikely to have arisen spontaneously. A current debate exists about whether life originated as replication or metabolism – or whether the two systems were ever separate before joining together in a symbiotic alliance.

In any case, although a variety of small scale biochemistries, with or without carbon, are possible – it seems likely that the structure of organisms of any substantial size will be built using polymers – which are large molecular structures, built up from the joining together of smaller units.

On Earth, we have proteins built from amino acids, DNA built from nucleotides and deoxyribose sugars – as well as various polysaccharides (for example cellulose or glycogen) built from other sugars. With microscopic biochemical machinery capable of building these small units and then linking them together – you can get organisms on the scale of blue whales.

Carbon is extremely versatile at linking together diverse elements – able to form more compounds than any other element we have observed. It is more universally abundant that the next polymeric contender, silicon – and it’s worth considering that on Earth, silicon is atypically 900 times more abundant than carbon – but still ends up having minimal engagement in Earth biochemistry. Boron is also very good at building polymers, but is a relatively rare element in the universe.

It does seem reasonable to assume that if we do meet a macroscopic alien life form – with a structural integrity sufficient to enable us to shake hands – it will most likely have a primarily carbon-based structure.

However, in this scenario you are likely to be met with a puzzled query as to why you seek tactile engagement between your respective motile-sensory appendages. Instead, why not offer to replenish each other’s solvents via some Goldilocks-zone heated water with an interesting nitrogen, oxygen, carbon alkaloid mixed in – something we call coffee.

Source: Universe Today