A molecular thermometer for the distant universe

Astronomers have made use of ESO’s Very Large Telescope to detect for the first time in the ultraviolet the carbon monoxide molecule in a galaxy located almost 11 billion light-years away, a feat that had remained elusive for 25 years. This detection allows them to obtain the most precise measurement of the cosmic temperature at such a remote epoch.

The team of astronomers aimed the UVES spectrograph on ESO’s VLT for more than 8 hours at a well-hidden galaxy whose light has taken almost 11 billion years to reach us, that is about 80% of the age of the Universe.

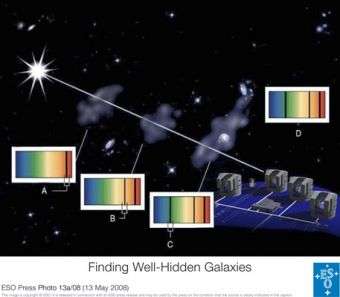

The only way this galaxy can be seen is through the imprint its interstellar gas leaves on the spectrum of an even more remote quasar. “Quasars are here only used as a beacon in the very distant Universe. Interstellar clouds of gas in galaxies, located between the quasars and us on the same line of sight, absorb parts of the light emitted by the quasars. The resulting spectrum consequently presents dark ‘valleys’ that can be attributed to well-known elements and possibly molecules,” explains Raghunathan Srianand (Pune, India), who led the team making the observations.

Thanks to the power of the VLT and a very careful selection of the target - the target was selected among about ten thousands quasars - the team was able to discover the presence of normal and deuterated molecular hydrogen (H2, HD) and carbon monoxide (CO) molecules in the interstellar medium of this remote galaxy. “This is the first time that these three molecules have been detected in absorption in front of a quasar, a detection that has remained elusive for more than a quarter century,” says Cédric Ledoux (ESO), member of the team.

The same team had already broken the record for the most distant detection of molecular hydrogen in a galaxy that we see as it was when the Universe was less than 1.5 billion years old.

The interstellar gas is the reservoir from which stars form and, as such, is an important component of galaxies. Furthermore, because the formation and the state of molecules are very sensitive to the physical conditions of the gas, which in turn depend on the rate at which stars are formed and their influence, the detailed study of the chemistry of the interstellar medium is an important tool to understand how galaxies form.

Based on their observations, the astronomers showed that the physical conditions prevailing in the interstellar gas in this remote galaxy are similar to what is seen in our Galaxy, the Milky Way.

But most importantly, the team was able to measure with the best ever precision the temperature of the cosmic background radiation in the remote Universe. “Unlike other methods, measuring the temperature of the cosmic background using the CO molecule involves very few assumptions,” declares co-author Pasquier Noterdaeme.

If the Universe was formed in a ‘Big Bang’, as most astrophysicists infer, the glow of this primeval fireball should have been warmer in the past. This is exactly what is found by the new measurements. “Given the current measured temperature of 2.725 K, one would expect that the temperature 11 billion years ago was about 9.3 K,” says co-author Patrick Petitjean. “Our unique set of VLT observations allows us to deduce a temperature of 9.15 K, plus or minus 0.7 K, in excellent agreement with the theory.”

“We believe our analysis pioneers interstellar chemistry studies at high redshift and demonstrates that it is possible, together with the detection of other molecules such as HD or CH, to use interstellar chemistry to tackle important cosmological issues,” adds Srianand.

Source: ESO