Newly solved structure reveals how cells resist oxygen damage

The sun’s rays give life, but also take it away. Singlet oxygen, a byproduct of the photosynthetic process by which certain cells convert sunlight into energy, is a highly toxic and reactive substance that tears cells apart. Now, in a study that took more than five years to complete, Rockefeller University researchers, in collaboration with a team of bacteriologists at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have become the first to solve the structure of a protein complex that protects these cells from singlet oxygen.

The findings, which appear in the September issue of Molecular Cell, not only advance knowledge of how cells sense the presence of singlet oxygen, but also how they turn on critical genes to defend themselves from its effects.

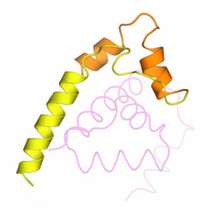

Using photosynthetic bacteria that generate this toxic form of oxygen, Elizabeth Campbell, a research associate in Seth Darst’s Laboratory of Molecular Biophysics, and her colleagues determined the unique arrangement of atoms in this two-protein complex, called σE/ChrR - and in the process, clarified the key to the structure’s function: a single zinc ion. While the Wisconsin team, led by Timothy Donahue, showed that ChrR binds zinc, Campbell and her team used X-ray crystallography to reveal how the two proteins, σ and anti-σ, work together to ward off singlet oxygen.

The crystal structure revealed that the anti-σ protein, ChrR, has two domains, each of which could bind the zinc ion. Under thriving conditions, when cells lack singlet oxygen, Campbell and her collaborators found that anti-σ needs this ion to latch onto its σ counterpart. In its clutch, anti-σ prevents σ from activating the genes that instruct the cell to neutralize singlet oxygen’s harmful properties.

The researchers further showed that anti-σ’s first domain, which has been preserved evolutionarily, does this by blocking the groove where σ binds RNA polymerase, the protein that initiates gene transcription. When the bacteria sense the presence of singlet oxygen, though, the anti-σ’s second domain responds by causing its first domain to release sigma. Now free, σ can initiate the events that protect the cell from damage.

What had come as a surprise to Campbell and her collaborators was that the second domain, the so-called sensing domain, had a zinc ion of its own, a particular feature not found previously in any other anti-σ. When Campbell’s collaborators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison removed the zinc-containing portion of the second domain and exposed the bacteria to light, the bacteria died, possibly suggesting that this second zinc is needed to initiate a process that protects the cell from this singlet oxygen.

“When a nation suffers calamities, it needs people on reserve and ready to go,” says Campbell. “Cells need the same thing, and these σs are its Coast Guards.“

Citation: Molecular Cell 27(5): 793-805 (September 7, 2007)

Source: Rockefeller University