Group Living Takes a Toll on Galaxies

Astronomers have detected substantial amounts of filamentary, cold gas in compact groups of galaxies, highlighting what may be an important force in galactic evolution, scientists announced today at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Calgary, Alberta. The findings also raise the intriguing possibility that more matter than previously thought may be tied up in these galaxy groups, captured in the lattice of the cosmic web.

The research is being presented by Sanchayeeta Borthakur, a doctoral student of Min S. Yun of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Lourdes Verdes-Montenegro of Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia in Spain also collaborated on the project.

Most spiral galaxies, such as the Milky Way, are brimming with cold gas that fuels the creation of stars—these young galaxies shine with bluish light and are scattered throughout the universe, often in little groups. Elliptical galaxies, on the other hand, tend to shine red and live a crammed existence with thousands like them in giant galactic clusters. These enormous, older galaxies no longer make stars—they have been stripped of their gas—which gets swirled into the cluster’s center, collecting in a massive hot soup that astronomers call the intracluster medium.

Recently astronomers have noticed that some groups of spiral galaxies don’t contain as much hydrogen gas as expected and are no longer birthing new stars, qualities usually found in older galaxies living out their years within a cluster.

“The spiral galaxies in the groups we looked at look old and tired—it’s as if they’ve prematurely aged,” says Yun.

Astronomers are still trying to figure out what happens between being a young, blue galaxy and an old, red one, says Yun. Perhaps group living was taking a toll on these young galaxies and, like the intracluster medium, the gravitational forces of an intragroup medium were stripping them of their star fuel. Presence of intragroup gas had been confirmed by recent observations using X-rays, but the amount of gas detected by the X-rays couldn’t account for the amount missing from the galaxies.

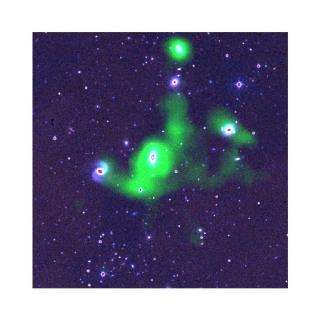

So Yun’s team began observing 25 Hickson Compact Groups—compact, relatively isolated, groups of galaxies, some of which had shown this mysterious gas depletion. The scientists used the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope, operated by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in West Virginia. The Green Bank Telescope uses radio waves and has a 100 meter aperture lens. It can point into the sky more precisely than one thousandth of a degree and is the most sensitive tool astronomers have for detecting neutral hydrogen gas in galaxies, gas not visible with X-ray observations.

The researchers detected far more gas than they would have imagined, says Yun. In groups dominated by spiral galaxies, the astronomers found about 50 percent more gas than they had detected using the NSF’s Very Large Array in New Mexico, also operated by the NRAO. And groups that had elliptical or lenticular galaxies had almost 100 percent more gas than had been previously detected. Just as surprising as the quantity of gas is its temperature, says Yun. The gas is cold and neutral, not the fiery hot gas of the intracluster medium.

Intracluster mediums have enormous amounts of mass, both from ordinary matter and dark matter, and hence have extremely strong gravitational fields. This can lead to excessively high temperatures—upwards of a million degrees—so astronomers hadn’t looked much for cold, neutral gas.

“It makes sense actually,” says Yun, the groups aren’t as massive as clusters, so the gas isn’t as hot. Borthakur’s calculations suggest that this gas can remain cold and neutral for as much as 100 million years or more in the group environment.

The findings suggest that this environment plays a far more important role in the evolution of galaxies than astronomers previously thought. “The local environment clearly can influence a galaxy’s gas content and its ability to form stars,” says Yun. Since these qualities are one measure of a galaxy’s age, the findings may prompt a re-evaluation of the cosmic clock, he says.

Another intriguing aspect of this cold neutral hydrogen gas is its distribution, says Borthakur. Analyses suggest that the gas forms sheet-like or filamentary structures, rather than a single diffuse cloud that surrounds the entire group. This raises the possibility that this intragroup medium builds up through the accumulation of matter from the cosmic web, the large scale structure that astronomers believe may link all of the matter in the universe, as predicted by the theory of dark matter.

“The only way a galaxy could be cleanly stripped of its gas is through a collision with more gas,” say Yun. Gas accounts for far more of a galaxy’s mass than its stars do, such that if an outer galaxy falls into a cluster its gas is stripped, subsumed by the intracluster medium. “A lot of the matter of the universe may be tied up in these small galaxy groups,” says Yun.

Future experiments designed to determine the temperature, density and the total mass of this intragroup medium will be able to determine quantitatively its origin and the importance of this gas in shaping the evolution of most galaxies.

Source: University of Massachusetts Amherst