New Clues in the Plant Mating Mystery

New data suggest that molecular communication between the plant sexes--specifically the pollen of males and pistils of females--is more complicated than originally thought. Plants, like animals, avoid inbreeding to maximize genetic diversity and the associated chances for survival. For decades, scientists have sought to fully understand the plant's molecular system for recognizing and rejecting "self" so that inbreeding does not occur.

Now, Bruce McClure at the University of Missouri-Columbia (UMC), together with his colleagues, report in the Feb. 16 issue of the journal Nature that plant "self" recognition systems involve multiple players and lots of male-female "conversation," at least at the molecular level.

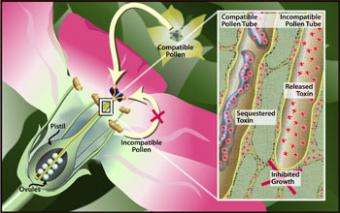

For successful reproductions to occur in plants, the pollen must make its way to the plant's female parts. That is, it germinates and grows within the pistil in order to reach the ovule. In one system plants use to prevent inbreeding, the pistil literally poisons the pollen en route to the ovule using a toxin known as S-RNase. Until now, the specifics of this self-incompatibility system perplexed scientists.

McClure and his colleagues showed that after the pistil injects S-RNase into the pollen, the toxin is whisked away to a holding compartment where it can do no harm until the "self" or "non-self" decision is made. McClure's work also suggests that at least three other proteins may be involved in this decision-making process.

McClure said, "What's really new here is the finding that pollen protects itself from the toxin in a different way than we previously thought, and we're starting to understand how these other proteins work together with S-RNase." McClure's group is now determining the molecular information responsible for the sequestering and release of S-RNase.

McClure also engages UMC freshman biochemistry laboratories in studying this plant self-recognition system to learn and perform advanced molecular biology. "It's a great system for helping students see how we connect genetics and biochemistry and use them to build an understanding of how living things work," said McClure.

McClure first showed that RNases were involved in controlling plant mating some 17 years ago. In 1994, he and Teh-hui Kao at Pennsylvania State University, both supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), independently determined the toxin's function. Recently, Kao's lab made another key advance by showing that a pollen protein called SLF helps pollen recognize S-RNase.

Susan Lolle, the NSF program manager for McClure's current research said, "This latest development in the pollen-pistil story is not only significant in its own right as we strive to understand the intricacies of plant breeding--it's also a great example of how stepwise advances in fundamental knowledge lead to our greater understanding of a complex system."

Source: NSF