First Measurement of Geoneutrinos at KamLAND

Results from KamLAND, an underground neutrino detector in central Japan, show that anti-electron neutrinos emanating from the earth, so-called geoneutrinos, can be used as a unique window into the interior of our planet, revealing information that is hidden from other probes.

“This is a significant scientific result,” said Stuart Freedman, a nuclear physicist with a joint appointment at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California at Berkeley, who is a co-spokesperson for the U.S. team at KamLAND, along with Giorgio Gratta, a physics professor at Stanford University.

“We have established that KamLAND can serve as a unique and valuable tool for the study of geoneutrinos with wide-ranging implications for physical and geochemical models of the earth,” Freedman added.

In a paper presented in the July 28, 2005 issue of the journal Nature, an international collaboration of 87 authors from 14 institutions spread across four nations has demonstrated the ability of the KamLAND detectors to accurately measure the radioactivity of the uranium and thorium isotopes, the two main sources of terrestrial radiation. The measurements the collaborators made are in close agreement with the predictions of the leading geophysical models of our planet’s thermal activities.

KamLAND’s geoneutrino experiment was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Our Mysterious Inner Planet

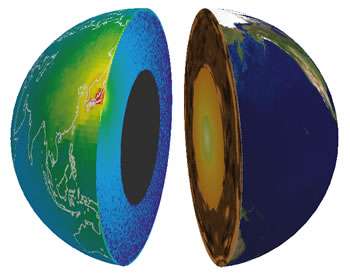

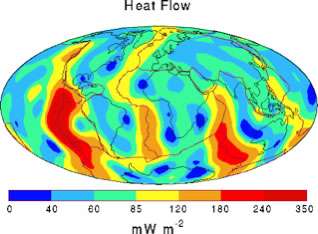

Surprising as it may seem, for all that we have learned about far distant astrophysical events like deep-space supernovae, dark energy, or even the Big Bang itself, the interior of our own planet remains a mysterious and largely unexplored frontier. Among the many questions is the source of terrestrial heat. The total amount of heat given off by the earth at any given moment has most recently been estimated at about 31 terawatts (TW). A terawatt is equivalent to one trillion watts. For comparison, the average energy consumption of the United States at any given moment is 0.3 trillion watts.

“Our results show that measuring the flux of Earth’s geoneutrinos could provide scientists with an assay of our planet's total amount of radioactivity,” said Freedman. “Measuring geoneutrinos could also serve as a deep probe for studying portions of the planet that are otherwise inaccessible to us.”

Said Stanford’s Gratta, “There are still lots of theories about what’s really inside the earth and so it’s still very much an open issue. The neutrinos are a second tool, so we’re doubling the number of tools suddenly that we have, going from using only seismic waves to the point where we’re doing essentially simple-minded chemical analysis.”

Added physics Professor Atsuto Suzuki, director of the Research Center for Neutrino Science, vice president of Tohoku University and spokesperson for the Japanese team at KamLAND, “We now have a diagnostic tool for the Earth`s interior in our hands. For the first time we can say that neutrinos have a practical interest in other fields of science.”

Dennis Kovar, Associate Director for Nuclear Physics of DOE’s Office of Science, agreed with Suzuki. "I believe the results of the multinational KamLAND collaboration are very interesting and indicate that science has a new, powerful tool for peering deep into the core of our planet."

KamLAND and Neutrinos

KamLAND stands for Kamioka Liquid scintillator Anti-Neutrino Detector. Located in a mine cavern beneath the mountains of Japan’s main island of Honshu, near the city of Toyama, it is the largest low-energy anti-neutrino detector ever built. KamLAND consists of a weather balloon, 13 meters (43 feet) in diameter, filled with about a kiloton of liquid scintillator, a chemical soup that emits flashes of light when an incoming anti-neutrino collides with a proton. These light flashes are detected by a surrounding array of 1,879 photomultiplier light sensors which convert the flashes into electronic signals that computers can analyze. The photomultipliers are attached to the inner surface of an 18 meters in diameter stainless steel sphere and separated from the weather balloon by a buffering bath of inert oil and water which helps suppress interference from background radiation.

Earth's conductive heat flow is estimated to be about 31 terawatts, nearly half of which comes from the earth’s interior. Radioactivity is known to account for some of this heat, but there has been no accurate means of measuring radiogenic heat production.

Neutrinos and their anti-matter counterpart, anti-neutrinos, are subatomic particles that interact so rarely with other matter they can pass untouched through a wall of lead stretching from the earth to the moon. Neutrinos are produced during nuclear fusion, the reaction that lights the sun and other stars. Anti-neutrinos are created in fission reactions, such as those that drive nuclear power plants, and in radioactive nuclei, such as uranium and thorium, that emit an electron and an anti-electron neutrino when they decay.

Anti-neutrinos, like neutrinos, come in three different types or “flavors,” electron, muon and tau, with the anti-electron neutrino, or geoneutrino, being by far the most common. Geoneutrinos can be detected and measured at KamLAND via a distinctive reaction signature after the subtraction of anti-neutrinos captured from nearby reactors and in background events from alpha particles.

“KamLAND is the first detector sensitive enough to measure geoneutrinos produced in the earth from the decay of uranium- 238 and thorium- 232,” said Freedman. “Since the geoneutrinos produced from the decay chains of these isotopes have exceedingly small interaction cross sections, they propagate undisturbed in the earth’s interior, and their measurement near the earth’s surface can be used to gain information on their sources.”

In measuring geoneutrinos generated in the decay of natural radioactive elements in the earth's interior, scientists believe it should be possible to get a three-dimensional picture of the earth's composition and shell structure. This could provide answers to such as questions as how much terrestrial heat comes from radioactive decays, and how much is a "primordial" remnant from the birth of our planet. It might also help identify the source of Earth’s magnetic field, and what drives the geodynamo.

The U.S. team at KamLAND includes researchers from Berkeley Lab, UC Berkeley and Stanford, plus the California Institute of Technology, the University of Alabama, Drexel University, the University of Hawaii, Louisiana State University, the University of New Mexico, the University of Tennessee, and the Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory, a DOE-funded research facility located at Duke University, and staffed by researchers with Duke, North Carolina and North Carolina State universities.

Berkeley Lab is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research and is managed by the University of California. Visit our Website at www.lbl.gov.

Source: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Much of this heat is re-radiated energy from the sun, but nearly half is produced from the earth’s interior. Radioactivity is known to account for some of this heat, but exactly how much has been difficult to say

because, until now, there has been no accurate means of measuring radiogenic heat production.These latest experimental results from KamLAND indicate that is no longer the case.