Engineering a new way to study hepatitis C

(PhysOrg.com) -- Researchers at MIT and Rockefeller University have successfully grown hepatitis C virus in otherwise healthy liver cells in the laboratory, an advance that could allow scientists to develop and test new treatments for the disease.

About 200 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C, which can lead to liver failure or cancer, and existing drugs are not always effective. To develop better treatments, researchers need to test them in laboratory experiments in liver cells, but it has been difficult to create a suitable tissue model because healthy liver cells tend to lose their liver functions when removed from the body.

Previously, researchers have been able to induce cancerous liver cells to survive and reproduce outside the body, but those cells are not sufficient for studying hepatitis C because their responses to infection are different from those of normal liver cells.

Now, Bhatia, in collaboration with Charles Rice of the Rockefeller University, has developed a way to maintain liver cells for four to six weeks by precisely arranging them on a specially patterned plate. The cells can be infected with hepatitis C for two to three weeks, giving researchers the chance to study the cells' responses to different drugs.

The new model, described in next week's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could allow researchers to test the effectiveness of various combinations of drugs, including interferon, a common current treatment, and experimental antibodies that may block the virus from entering cells.

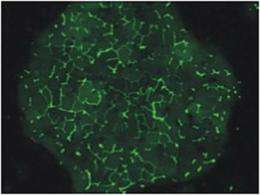

The researchers used healthy liver cells that had been cryogenically preserved and grew them on special plates with micropatterns that direct the cells where to grow. The liver cells were strategically interspersed with other cells called fibroblasts that support the growth of liver tissue.

"If you just put cells on a surface in an unorganized way, they lose their function very quickly," says Bhatia. "If you specify which cells sit next to each other, you can extend the lifetime of the cells and help them maintain their function."

The current system may already be suitable to screen drugs against the strain of hepatitis C used in this work; however, this strain, which was derived from a Japanese patient with fulminant hepatitis is the only strain ever successfully grown in a laboratory environment. The researchers hope to modify the system so they can grow additional strains, such as those more common in North America, which would allow for more thorough drug testing.

More information: "Persistent hepatitis C virus infection in microscale primary human hepatocyte cultures," Alexander Ploss, Salman Khetani, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, week of Jan. 25, 2010.