This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Researchers ID protein that helps cancer cells in cell division process

An MUSC Hollings Cancer Center research team has identified a protein that helps cancer cells to organize themselves in a way that allows them to successfully navigate the cell division process despite an abnormality that should doom them. Targeting this protein could throw the cancer cells into disarray, leading to cell death among the cancer cells while leaving normal cells untouched, the researchers have demonstrated.

The team from the lab of Ozgur Sahin, Ph.D., the SmartState Endowed Chair in Lipidomics and Drug Discovery in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, published its findings in the journal Cell Death & Differentiation.

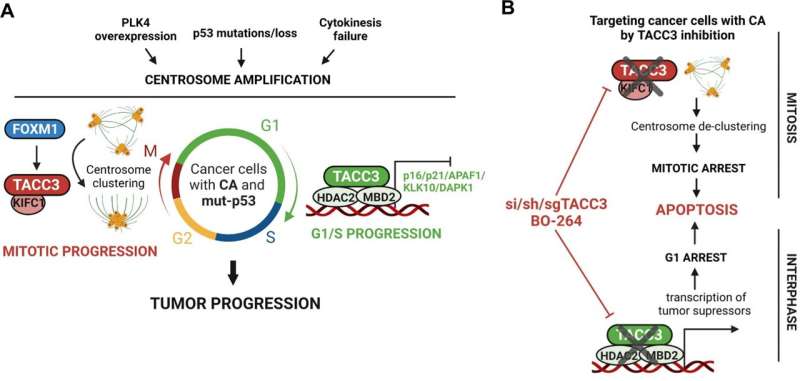

The research looks at centrosome amplification and centrosome clustering, two relatively unknown phenomena in cancer cells.

"Centrosome amplification is one of the hallmarks of aggressive cancer," explained Ozge Saatci, a graduate student who was first author on the paper and who received a scholar-in-training award from the American Association for Cancer Research to attend its conference in April and present the research.

During the cell cycle for normal cells, a centrosome duplicates itself to become two centrosomes in preparation for cell division. Those centrosomes then organize the physical infrastructure so that each copy within a pair of chromosomes migrates to opposite sides of the cell, which then pull apart to form two daughter cells, perfect copies of the original.

Cancer cells, however, tend to have multiple centrosomes. Although it is advantageous for cancer cells to have multiple centrosomes, in terms of increased tumorigenicity and metastatic potential, it also poses a problem during cell division. Instead of two halves pulling apart neatly, each centrosome would pull in its own direction, pulling the cell apart into multiple daughter cells without full sets of chromosomes. That would cause the cancer cells to die—except that they get around this problem using a tactic known as centrosome clustering.

In centrosome clustering, the extra centrosomes bunch together as if there were only two centrosomes in the cell. This allows the cancer cells to divide in half and survive.

The Hollings researchers identified a protein called transforming acidic coiled-coil containing protein 3—or TACC3—as responsible for ensuring that these cancer cells with extra centrosomes survive and thrive through the cell division process. TACC3 is overexpressed in tumors with centrosome amplification, meaning that more TACC3 is there than should be.

"TACC3 is an important component of this centrosome clustering machinery," Sahin said. "They cluster the centrosomes as one; then they pull. They divide properly; then they can again behave as centrosomes amplified. But this process is happening just in cancer cells, not in normal cells. That's why if you target centrosome clustering, then you are uniquely targeting cancer cells and saving the normal cells.

"In chemotherapy, the major problem is you are killing all dividing cells," he continued.

Killing off all dividing cells, whether they're cancer cells or normal cells, leads to the side effects that many patients endure.

Sahin and Saatci said that not only would targeting TACC3 eliminate the problem of killing off normal cells, but it would also mean that cancer cells could be killed during multiple stages of the cell cycle instead of waiting for the division, or mitotic, stage. At any given time, most cancer cells will be in the interphase stage rather than the mitotic stage.

"This protein that we are targeting acts in both mitotic and interphase—it has unique functions throughout the cell cycle," Saatci said. "The mitotic inhibitors that are being tested in clinical trials target only the mitotic cells, and that's why the efficacy is low, and toxicity is high. But for our target, we expect this will be effective in both mitotic and interphase cells, so it will most probably have better efficacy."

The Hollings researchers noted that high levels of TACC3 are associated with worse outcomes, particularly for patients with triple negative breast cancer.

The team is continuing to study TACC3 and mitosis, saying that much remains unknown about how this most basic of cell functions occurs.

More information: Ozge Saatci et al, Targeting TACC3 represents a novel vulnerability in highly aggressive breast cancers with centrosome amplification, Cell Death & Differentiation (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41418-023-01140-1

Provided by Medical University of South Carolina