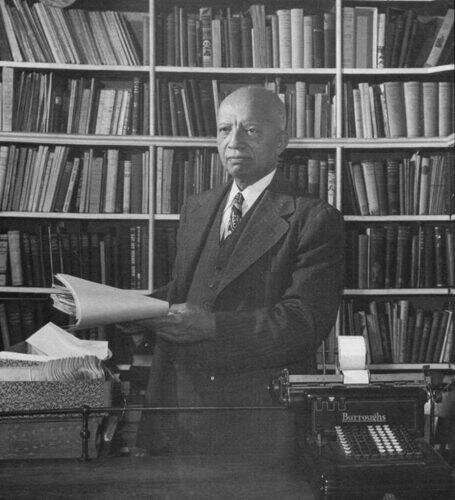

Carter G. Woodson. Credit: Smithsonian Institution

Although Black History Month wasn't established until the 1970s, Black teachers in the segregated Jim Crow South, particularly women, had been teaching Black history for decades prior, and were vital to its accuracy and preservation.

That's according to ArCasia James-Gallaway, a professor in the Texas A&M University School of Education and Human Development and an interdisciplinary historian of education who focuses on African Americans. She says much can be learned from these early educators, who worked to infuse culturally-relevant lessons into their classrooms, as well as instill a sense of pride in their Black students.

By analyzing archival and other written documents, as well as drawing on oral history, James-Gallaway found that these educators affirmed their students' cultural, racial and political knowledge, worldview and assets by teaching critical, politically and culturally-informed lessons.

False narratives

During the era of segregation when Jim Crow laws prevailed, prevalent ideas for most of U.S. history, "promoted the notion that Black people either had no past—or one not worth studying—or that our history began at enslavement," James-Gallaway said. Another camp romanticized life in Africa by assuming everyone was royalty.

Arguably the first to institutionalize what we now know as Black History Month, writer and historian Carter G. Woodson made some of the most notable efforts to shift these false narratives. Beginning with what was early-on known as "Negro History Week," Woodson helped lay the foundation for what expanded to Black History Month.

"This initial week started in the 1920s during, in the South, de jure [legalized] segregation or Jim Crow," she said. "Over time segregated Black schools, among others, used this week as an occasion to dedicate focus to a history many had been taught did not exist. But it was a process."

The 1970s saw the one-week recognition shift to a full month. "Woodson, however, was certainly not the first to integrate, albeit on a smaller scale, Black history into his own instruction or curriculum, as myriad Black teachers across the South, Black women in particular, had been doing so for decades," James-Gallaway said.

"In many ways, the South is central because you can't fully understand the history of this country without a deep understanding of the South, and that African Americans have played and continue to play an essential role in it," she said. "Many of Woodson's writings reveal his frustration [about] and disdain for the widescale erasure and distortion of Black history."

She said Black educators fought to challenge harmful mischaracterizations like "the happy slave," which purported that enslaved persons were docile, unthinking, enjoyed enslavement, and relished good treatment from their white enslavers.

"This trope underwrote the belief that Black people would not know what to do with freedom because they did not understand how to take care of themselves," James-Gallaway said. "Such ideas were prevalent throughout textbooks used in Black and white schools for decades, and it grew out of so-called historical research conducted by white historians."

Many related ideas persist about Black people as subhuman and unintelligent, James-Gallaway said, noting, "Broadly, we can think of this as 'anti-Blackness,' which I hold as synonymous with 'anti-Black racism' and define as structural or institutional acts and supporting ideologies that oppress, subjugate, or subordinate Black peoples."

She added that a recent move to block access to an AP African American Studies course is an example of the same efforts to distort Black history that occurred during segregation.

Work to emulate

The work of Southern Black educators during segregation is a rich site of knowledge for today's educators, James-Gallaway said.

"I really admire educators whom I've found in my research that worked with—or sometimes against—their administration to subvert the system of white supremacy and anti-Blackness, and teach against the grain," she said.

The most gifted Black educators of the past, like many today, took a holistic approach to education. "It was about educating the whole person spiritually, psychologically, culturally, and of course academically," James-Gallaway said. "Studying [the work of] Black women teachers of the South shows us that the best teachers understand that there is far too much at stake to go about their job as if education is an apolitical endeavor with immaterial consequences for oppressed and marginalized communities."

Provided by Texas A&M University