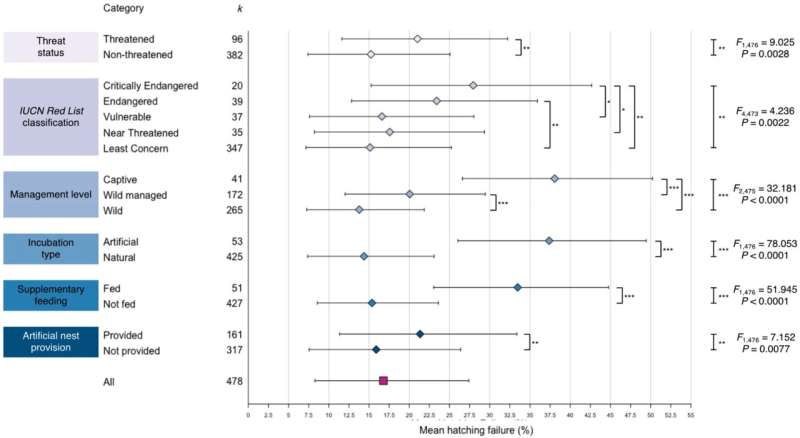

Forest plot of the mean effect size (hatching failure percentage) estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each factor level for six moderators: threat status, IUCN Red List classification, management level, incubation type, supplementary feeding, and artificial nest provision. Random effects for each model were effect size ID, study ID, species name, and phylogenetic history. Proportions were transformed using a Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation, and all models were fitted using a restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation with a Knapp–Hartung adjustment. A significant F statistic indicates that at least one of the regression coefficients of the moderator categories significantly deviates from zero, indicating that that moderator influences hatching failure. Significant differences between levels are also shown. The mean hatching failure percentage for the whole final data set is shown for comparison (red square). Estimates were back-transformed with the inverse of the Freeman–Tukey transformation using the harmonic mean of the sample sizes and are presented here in the natural scale. k = number of effect sizes. Levels of significance across categories and levels: ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. Credit: Biological Reviews (2023). DOI: 10.1111/brv.12931

Hatching failure rates in birds are almost twice as high as experts previously estimated, according to the largest ever study of its kind by researchers from the University of Sheffield, Institute of Zoology, and University College London (UCL).

The new report, published in the journal Biological Reviews, highlights how conservationists can best support the recovery of threatened bird species, as it outlines how different conservation practices may affect hatching rates.

The researchers looked at 241 bird species across 231 previous studies to examine hatching failure. They found that nearly 17% of bird eggs fail to hatch—almost double the figure reported 40 years ago of just over 9%.

The findings suggest that more than one in six bird eggs fail to hatch, and the numbers are even more stark in endangered species—almost half (43%) of eggs from threatened species that are bred in captivity are unsuccessful in hatching, which presents a major barrier to their recovery as a species.

Dr. Nicola Hemmings, co-author from the University of Sheffield's School of Biosciences, said, "Around 13% of bird species globally are currently threatened with extinction, and things are getting worse instead of better. Species on the verge of extinction have much higher levels of hatching failure compared to non-threatened species, and breeding birds in captivity appears to be having a negative impact.

"There are important considerations that we need to make—does the benefit of captivity and other interventions outweigh the reduced reproduction of these species? For many species, these practices are absolutely vital for species survival,, so we need to carefully weigh up the pros and cons of different approaches to ensure that we are doing everything that we can to protect birds from extinction."

The findings outline four different conservation practices that were associated with lower hatching rates:

- Birds kept in captivity compared to being in the wild or free living

- Eggs hatched in artificial incubators as opposed to natural nests with parental incubation

- Birds being fed supplementary food

- Birds using artificial nest boxes/sites instead of natural nest sites

However, despite any potential negative impacts these have on hatching, they may still be important to birds' reproduction and survival—for example, the eggs of some ground-nesting birds are at such high risk of predation that leaving them in wild nests would result in all of the eggs being destroyed.

As a result, there are pros and cons of each conservation technique, and the researchers hope that these findings will act as a framework for conservationists to assess what the best strategy is for each species of bird, to make sure that they have the best hatching chance while also keeping them safe.

Dr. Patricia Brekke, Co-Author from the Institute of Zoology, ZSL, said, "With this work we hope to provide vital evidence needed to understand how effective different management practices are at improving hatching success and aid population recovery.

"Conservation managers are doing an amazing job of preventing species decline, but they have an incredibly difficult job of making decisions when species are at the brink of extinction, on what tools to implement, and when. This kind of work provides the evidence necessary to improve decision making and hopefully improve recovery."

There are several factors that may explain why hatching rates have declined in recent decades, including populations dropping and extinction becoming more common. It is currently unclear, however, whether current population declines are being driven by increased hatching failure rates, or alternatively if reduced hatching is a consequence of population decline.

Ashleigh Marshall, Lead Author from the Institute of Zoology, ZSL and UCL, said, "Many of the previous comparisons of hatching failure across birds have typically excluded managed populations and have focused on non-threatened species only, which could mean we've been missing a big bit of the picture.

"A key takeaway of this work is that it could show that populations already experiencing high rates of hatching failure are more likely to be taken into captivity or otherwise managed, which would indicate that conservation efforts are fittingly being targeted towards the species that need it most."

The researchers have also called for a standardized definition of hatching failure, as their literature review revealed broad inconsistency with how it is defined and reported. This would help to track how hatching failure changes in the years to come, and may also benefit other types of egg-laying animals, such as reptiles and amphibians, where there are also widespread issues with hatching failure.

More information: Ashleigh F. Marshall et al, Systematic review of avian hatching failure and implications for conservation, Biological Reviews (2023). DOI: 10.1111/brv.12931

Journal information: Biological Reviews

Provided by University of Sheffield